PROFILE

10 Nov 2025

NICK SCHLIEPER

Subscribe to CX E-News

When I speak to Nick Schlieper over Zoom he is recently returned to Australia after having spent just shy of 48 hours in New York. Nick was attending the Tony Awards where he was nominated for his lighting design on The Picture of Dorian Gray. The Music Box run of the production was nominated for six Tonys, and took home two.

It’s surely the dream of every young, starry-eyed emerging designer to one day be in the running for a Tony. Unfortunately for Nick, his time in New York coincided with him having a kidney stone. “I went through the entire seven-hour long ceremony in a miasma of cross-eyed pain, just wanting the damn thing to be finished.”

While he’s yet to receive a Tony, Nick is one of Australia’s most awarded designers, having received multiple Green Room, Sydney Theatre, and Helpmann Awards over his career. For many years he has been in the incredibly fortunate position of being able to be selective about which projects he takes on and, more specifically, which projects he turns down.

Like anybody, he started with little knowledge and experience and gradually built his expertise and, like so many theatre professionals, Nick’s starting point was “the great old cliché of that one particular schoolteacher.” Nick is unclear on exactly what this teacher’s experience was, “He had some kind of background in theatre in a previous life that was a bit of a taboo subject, we all kind of knew not to go there.” But his impact was undeniable, “He was the most inspiring and inspired teacher imaginable.”

Nick describes his high school as “bog standard” and says there was “nothing as grand as a drama department,” but there was a group of students who put on plays. In his final year, Nick worked on lighting and set design for five shows. Despite this much extra-curricular activity, he achieved the marks to get into an Arts Law degree. “I got all the way to the sandstone portals of Sydney Uni for orientation day. I stopped at the threshold and looked at all of these kids lugging their backpacks full of books. I had this moment of thinking – this is what I’ve just done. This feels like a wrong move. I turned on my heel and left.”

Fortuitously, Nick ran into his inspiring modern history teacher as he got off the train that afternoon. He told Nick to go home and ring NIDA straight away. Although he’d missed the admissions window for that year, Nick worked on an application and was guaranteed a spot at NIDA for the following year. “It was the best thing that could’ve happened because I knew in a year’s time I had a place. By the time that year was up, I was working at the Old Tote, the forerunner of the Sydney Theatre Company. I had a permanent job as a stage manager and when NIDA started ringing asking where I was, I looked a long way down my nose at them and I said, ‘I don’t think I require your services anymore’.”

Given the breadth of Nick’s work as an LD it’s hard to imagine him doing anything else, but there was a time early in his career when he desired to be a director. The pathway to becoming a director back then was via stage management. “The SM was very much the director’s right hand.” Nick figured out “pretty damn quickly” he was never going to be a good director, but he was a really good stage manager.

Although Nick describes this four-to-five year period of his career as a side-step, it has informed his work as a designer. Because of the SM’s pivotal role in the larger structure of a company, Nick interacted with everyone from the box office to publicity. “It gives you a really good bird’s eye view of all of the bits of a jigsaw puzzle that go into making a show.”

His experience calling large scale productions gave him lots of practice at cueing. Not just with lighting cues, but all aspects of the show and how they interlock together. He’d be approaching the same operatic scene change each night and would think, “if that fly cue went on that note of music and the lighting cue went with it, instead of two bars before, etcetera. I got really annoyed about it, but that showed how much I was learning.”

In this era, he also worked as a production manager, which taught Nick about financial planning and budgeting, including how to front up to boards and ask for more money. “I would say that knowledge has been more useful to me than being able to plug a light in and make it work with wireless DMX.”

“I’m a crap technician,” Nick says. “I always have been, and I always will be. I’m not interested in it. I don’t have the aptitude for it. I’ve certainly never learned the skills. I don’t need them, no more than I need to be able to learn how to operate a lighting console. There are people who specialise in that who are highly skilled and qualified. Let the people who are good at it do those things. I’m not in any way putting down the work of technicians. Quite the contrary actually. I can’t do it. But I don’t think being able to do it makes you a better designer.”

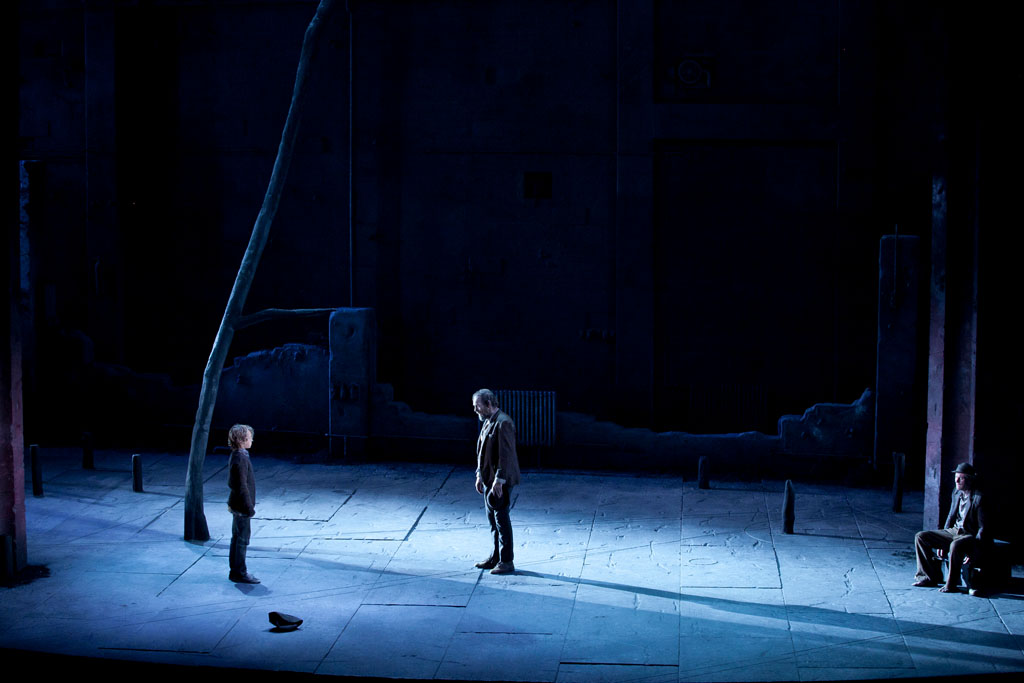

In terms of where Nick did learn the fundamentals of lighting design, he did a course with British lighting designer David Read in ‘77. The Australia Council had brought David to Sydney and eight people, who were already working in theatre, were selected to partake in six months of tutelage. “In some ways it was a bit of a joke,” says Nick. “It became a beer drinking competition. He was very much a British lad and down at the pub every five minutes.” Nonetheless, Nick gathered the fundamentals in British 1960s methodologies of lighting box sets. “He was able to contextualise that old school methodology with slightly newer ways of thinking.” This style had an emphasis on lighting actors, something Nick says can be undervalued and, decades into his career, still sees as a crucial part of his aesthetic. “Once you have people sitting 60 and 70 metres away from the stage you have to have some tricks up your sleeve to overcome that physical distance barrier to appear to make that face more present than it really is.”

It can be hard for Nick to be any more specific about what his style largely is, in part because technique is something that shapes and shifts very gradually over time. For instance, it wasn’t until years later when Nick began to teach lighting design himself and he returned to his notes from David Read, that he realised he had thrown away the old McCandless theory – a lighting technique whereby you light a face using two lights, each from a 45 degree angle. “45 degrees is way too flat. I hate it. It’s 60 one way and 80 the other. That’s what my eye likes, that’s my taste.”

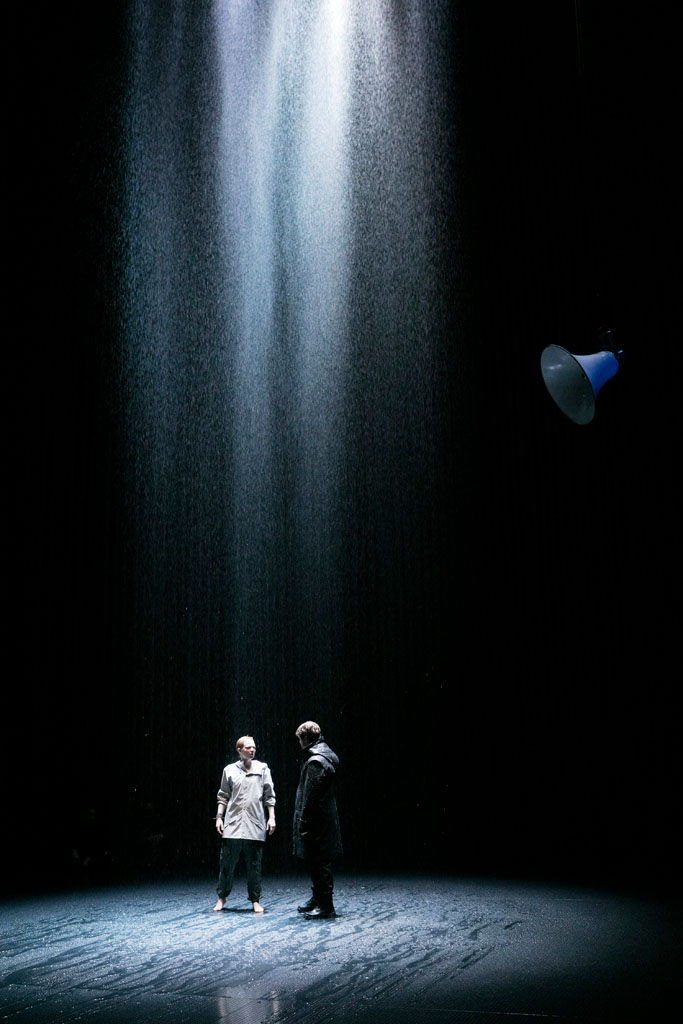

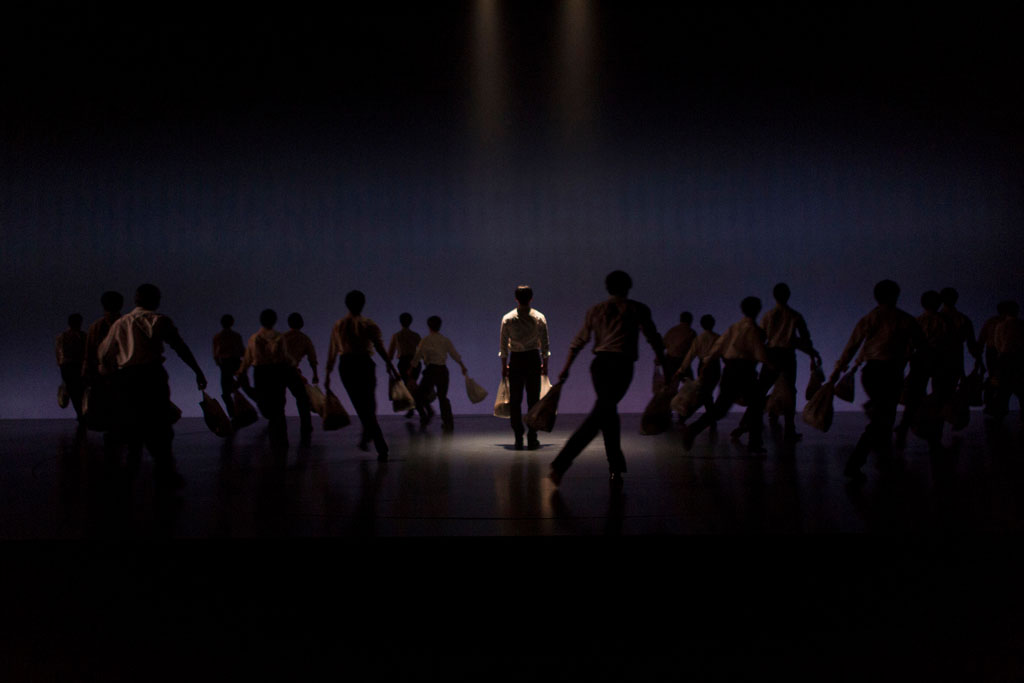

It’s harder to narrow down style more so because Nick rejects the idea that a design can be approached in any formulaic way. “I might be kidding myself, but I really, really, really try to approach every single show as its own thing. If you stop at least giving this a noble attempt, then it’s time to get out of the game,” he says. Ultimately Nick believes theatre to be an act of communication between human beings at one end of a room to human beings at the other end with light working as an enabler for that communicative pathway. “Telling an audience how to think, why to think, where to think, let alone where to look.” And Nick describes this part of the gig as “the fun bit”.

“It’s the greatest audience manipulation tool in the kit.” While sound can possibly do it to a greater degree, an audience realises when they’re being manipulated by a sound cue because they can hear it, but if you bury your lighting cues carefully enough and time them carefully enough, you can pull the audiences’ strings without ever being seen to do so. “I would say somewhere between half and three quarters of the cues I make in a year will be designed to be completely invisible. That is so ingrained in my thinking I can’t imaging not doing that.”

Even still, Nick maintains it’s impossible to make sweeping statements about anything. As he forms a sentence all the exceptions to the rule come to mind. “The biggest fundamental is that you have to do everything to realise the jointly agreed amongst you vision you started with.” This speaks to the core meaning of what a designer is. “In one way or another, I have a picture in my head and the technical skills allow me to take that picture and put it into whatever situation that is. In this case a stage.” Unfortunately, this is one of the many babies that Nick fears is being thrown out with the bathwater in how we’ve integrated modern lighting technology. “There’s a whole bunch of technique that is gone because you don’t have to commit in advance. You don’t have to have a picture in mind, you can just have a bunch of ingredients, a rig of potentials.”

This shouldn’t be mistaken to mean that Nick is a Luddite. In particular, he thinks the development in consoles is significant and mostly for the better. “I find more and more that I’m treating channels within cues as individual entities and not just a block of light. I can control one channel, give it its own time and delay.” And he does use moving lights and LED. “I use them quite a lot. They have their purposes to my mind. Like any other tool, you use it where it’s applicable.” But given Nick’s penchant for lighting actors, he could never rely entirely on LED, as he would lose the part of the visible colour spectrum that pertains to the facial tones of white people. “Everyone says you can’t tell the difference between LED and tungsten on a white wall, but if you hold your hand in it – one hand is the colour of my hand and the other looks grey.” He wonders how people use LEDs for front of house light when you can’t peak the lamp. “The whole 50 per cent overlap from lamp-to-lamp, it’s all gone out the window and no one seems to give a shit because they don’t have to make a decision about colour in advance.”

With a career as long and impressive as Nick’s he maintains it’s impossible to choose a favourite show. “One tries to love as many of one’s babies as possible.” But, he concedes, because of the sheer scale and the amount that it took over his life, when asked this question he cannot go past the South Australian State Opera’s 2004 production of the Ring Cycle, Australia’s first ever production of Wagner’s behemoth. “I think it’s still one of the biggest shows that’s ever been put on in this country indoors.” It included an 18 metre wide and one metre high bar of flame that flew. A two-metre-high ring of 12 flame burners than came up through the floor. It is the only time, Nick believes, that he has rigged a thousand lamps. “In every respect the thing is a fucking monster and we pulled it off.” But, like all of Nick’s answers, he refutes any simple truth of this being his one best show. He refers to the ‘golden era’ of STC when Cate Blanchett was co-Artistic Director of the company with her husband and starred in several shows Nick lit – Hedda Gabler, Streetcar Named Desire, Uncle Vanya, Big and Little, The Maids and The Present. And he notes the work he has done with the Bavarian State Opera.

I’ve interviewed many lighting designers for this magazine and not one interview goes by without the subject mentioning Nick and his work, always with reverence. If he gives his projects the complexity, earnestness and generosity he has given the answers to my questions – and I suspect he gives much, much more – it is no wonder he has become one of the country’s most in-demand designers. If there is one part of our conversation he seems to have little interest in, it is the Tonys. Kidney stone aside, it seems the real prize for Nick is the work itself.

Nick Schlieper is one of Australia’s most highly awarded designers, having received five Helpmann awards, seven Sydney Theatre awards (including two for Set Design) and six Green Room Awards. This year he was nominated for a Tony award, for The Picture of Dorian Gray on Broadway.

His 104 productions for Sydney Theatre Company most recently include set and lighting designs for Happy Days, (which he also co-directed with Pamela Rabe).

2025 has also seen him light Love Never Dies in Tokyo, The Picture Of Dorian Gray on Broadway, Grief Is The Thing With Feathers (also Co-Adaptor and Set Designer), and Orlando for Belvoir St and The Lady From The Sea for London Theatre Co at The Bridge Theatre. In December, he’ll start rehearsals for Dracula on the West End, starring Cynthia Erivo.

Subscribe

Published monthly since 1991, our famous AV industry magazine is free for download or pay for print. Subscribers also receive CX News, our free weekly email with the latest industry news and jobs.