News

18 Sep 2018

Aida

Subscribe to CX E-News

Feature

Aida

by Cat Strom

Photo Credits: Prudence Upton

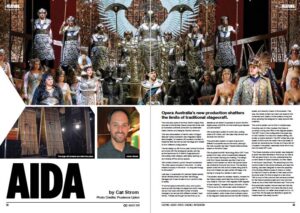

Opera Australia’s new production shatters the limits of traditional stagecraft.

The most epic opera of all time, Verdi’s mighty Aida returned to the Sydney Opera House this winter with an Australian premiere production by celebrated Italian director and designer Davide Livermore.

This new interpretation of Verdi’s vision of Egypt featured Opera Australia’s new integrated digital technologies; 10 massive LED screens mounted on theatrical flats that slid across the stage and rotated to form different configurations.

The set design by Giò Forma used minimal furniture and props with the rectangular panels, serving as the backdrops for D-Wok’s imaginative and stimulating video designs, alternately opening up and closing off the various spaces.

OA’s Artistic Director Lyndon Terracini exclaimed: “No other opera company in the world – no other theatre company in the world – is using technology to this extent.” Last year, in preparation for planned digital operas, Adrian Riddell joined OA as their Technology Manager and it was his task to turn Lyndon’s idea to reality.

Adrian Riddell, OA Technology Manager

“A normal opera is set within a box, and Lyndon came up with the idea of a digital box which means we can now have unlimited number of scene changes in an act just with different content,” said Adrian. “Initially we thought we had time up our sleeves as we weren’t supposed to launch the first digital opera until 2019, but the timeline got stepped up quite rapidly!

OA’s automation system is brand new, costing close to $1 million, and next year they will add two revolves into the floor. The automation system is made of parts from different companies around the world, although the main supplier has been Theatre Safe Australia based on the Gold Coast.

TSA supplied the EXE Technology 52cm DST Truss system from Italy, which is specifically designed for LED screen tracking and rotating. The design brief from Opera Australia was that it had to be loaded in and loaded out within the typical Opera rep timeframe of around two hours. The resulting system does this with all the trusses being able to drop onto trolleys and get pushed off stage, only having to unplug four cables on each truss. “The system allows for endless rotation, however for the Opera project we limited the control system to only rotate to -540 and +540 degrees (1080 degrees of total rotation),” revealed Stuart Johnston of TSA. “This is due to the LED screen cable limitations.”

The system is controlled and powered by a Raynok control system, which does a live multicast output to the disguise media servers with the X&Y Position, speed, and velocity of each of the screens. That way, the media content can track and adapt to the movement and rotation of the screens during the show, allowing the designers to really explore their creativity.

The control system can do this in multiple ways, including over Art-Net, however the Opera is currently running over PSN to the disguise system. The DST Truss in the configuration the opera has it built in allows it to track and rotate a 900kg LED screen or scenic element. The DST trolley has a top speed of 20m/s and the rotator has a top speed of almost six revolutions per minute, so it has a fair bit of speed in the system, especially since this is only the mid-sized DST truss.

“The Opera Australia control system was designed to allow the client flexibility in the future, so here at TSA we spent time in not only understanding the current needs of Opera Australia, but their needs in the future,” said Stuart.

“So everything from the control drives to the control software, and even the cabling, has been designed to have the capability of controlling different types of motors or hoists so they don’t have to reinvest in their base control structure when it’s time to adapt to a new show.

“TSA is proud of the outcome that we have provided for the Opera Australia project and one comment made by one of their staff members was ‘This is the first automation system that we have had that has just f*%^$#g worked’! Comments like that is what makes us proud, no matter what project it is on. To us at TSA, it’s the ease and flexibility it gives the creative team that really counts.”

“TSA is proud of the outcome that we have provided for the Opera Australia project and one comment made by one of their staff members was ‘This is the first automation system that we have had that has just f*%^$#g worked’! Comments like that is what makes us proud, no matter what project it is on. To us at TSA, it’s the ease and flexibility it gives the creative team that really counts.”

Big Picture were asked to come up with a video solution with various suggestions from creatives. Ideally they wanted to project to all the screens, but technically that was not possible, especially in the time frames for resetting the stage.

“There were other technical disadvantages such as shadows created on the panels when people walked in front of them, so we chose to go with an LED option,” said Adrian. “This is custom 3.9mm LED product developed by Big Picture that has a unique combination of LED and processing which gives us really good colour grading for the images. We only run them at 6%.”

The visual elements of the show are the result of 175 square meters of 3.9mm LED with Brompton Processing arranged into 10 columns 7m tall by 2.5m wide. These are all driven by a fully redundant disguise 4×4 Pro media server system.

In addition to the LED outputs there is also a front and rear projection element being serviced with Barco UDX-4k32 laser projectors, the RP utilising one of the new 0.4: UST Lenses. The disguise system is managing four 4k content layers as well as dealing with incoming data streams from the SOH fly system from Wagner-Biro, the Opera Australia automation system from Raynok that manages the individual screens tracking and rotation, as well as the lighting RF tracking system from Zactrack. Finally, show control is being generated by the ETC lighting console.

“It has been a task in itself to create a base file within disguise that has all of these external data parameters already written in so that we can distribute the base file to all of the upcoming productions that will be using the digital setup,” added Nick Bojdak, Big Picture’s Account Manager. “We are expecting productions to implement Notch effects into their visuals at some point in the 2019 season.”

“The first year is a bit of an interesting one-off in that Aida is in rep with Rigoletto and Lucia, which are both traditional set designs, so although we are only dealing with one creative team utilising the digital platform it means that the entire stage infrastructure needs to be installed before every show and removed afterwards so another set can be installed.

“The main challenge here was to be able to install 175 square meters of hi-res LED in two hours and then be able to remove it in one hour. We got creative with some customised set carts and some specialised locator pins which enable us to break the screens down into 2.5 by 2.0m sections.

“This method of building LED is not new but it has not been widely adopted with hi-res products as inherently they are far more fragile due to the large number of LEDs so close to the edge of the panels, as well as the precise manufacturing tolerances required for a seamless wall. So far we have been really happy with how the product has stood up to the rigorous in and out schedule.”

The OA production team did a test build at Red Box in Lilyfield a month prior to loading into the SOH. The automation system was built, screens were hung to work out where cables would

come down through fly bars, and a little bit of reconfiguration saw everything fall into place.

The SOH’s Joan Sutherland Theatre had its own inherent problems; it’s a small venue, so when the screens go off stage there’s no stage space for cast members. Working out how to mask off stage pieces as well has been a challenge. Creatives turning up with content late in the day was problematic too.

“We tried to put policies in place to get information before they arrived so we could have some of it pre-programmed but things changed,” said Adrian. “With a traditional opera the set would have been built months beforehand but with the ability to change content relatively quickly, you can theoretically change stuff on the fly.”

Having said that, some of the content took a long, long time to render. The large black panther took a whole month to render and could not be changed! As with the use of any new technology there will be teething problems at the start. Unfortunately in this case it was opening night when one module (out of over 1400) was intermittently misbehaving.

Having said that, some of the content took a long, long time to render. The large black panther took a whole month to render and could not be changed! As with the use of any new technology there will be teething problems at the start. Unfortunately in this case it was opening night when one module (out of over 1400) was intermittently misbehaving.

“After working perfectly for six rehearsals and a full kit check that day, it decided not to play the game,” lamented Adrian. “It’s the opening night bug, but we sacrificially burnt that module afterwards. Touch wood, we haven’t had a problem since.”

Lighting designer John Rayment had to ensure that the lighting responded to, and coexisted with, the LED content and the technology. The context being that OA is moving towards the implementation of a new standard lighting rig, proposed to be entirely of robotic LED luminaires, wash and profile.

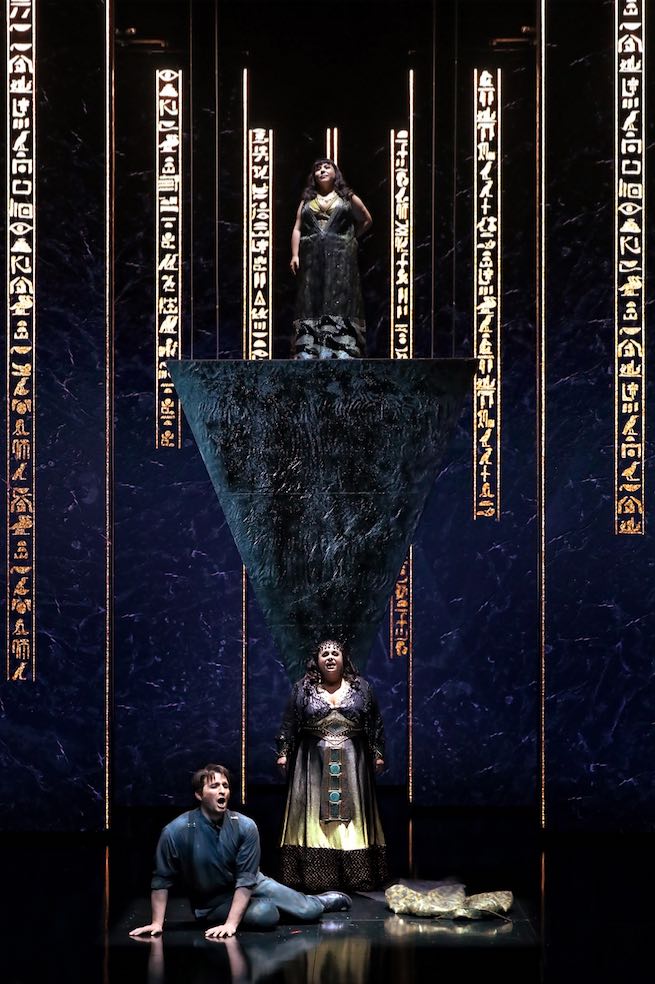

The design for Aida had to anticipate, as far as was practical, that new environment given that the production is expected to stay in active rep for many years. With the physical staging environment always changing, with the five pairs of LED screens rotating and tracking, there was sometimes a quite complex requirement for lighting transitions to work in and around the staging animations.

“Every effort was made to avoid light hitting the screens although that was not always possible,” said John.

“The LED screens are forgiving, at times, when the content is dominant. A carefully choreographed sequence of lanterns handing on to other lanterns as artists moved about would assist in minimising the spill angles although that, of course, presupposes that those artists will be consistent in their blocking which is difficult with different casts through a season.”

Responding to the content – colour, brightness, strong accent lighting within the content and so on – was obviously a major factor and it was hoped that artists and the analogue stage will look to belong with the digital content around them.

“This underlies any designed stage lighting, of course,” added John. “Colour is both relative and subjective. The core response is to the dominant feature, then to fold all the other elements into a credible lit environment. The other keys are always present, such as making the most of facial tones, particular costumes, and furniture.”

John reports that brightness was an issue at times saying a median intensity was set for the screens and they then sought to adjust specific content streams within the media server.

“We did not have control of the screen brightness at the lighting console, which I would seek to have in future as there are occasions, in my view, when the LED screens do need to be treated as lights operating as part of the larger design.”

It was the intention to deploy tracking technology for the lighting, such that nominated artists would be fitted with unique identifiers and that (notionally) any robotic lantern in the rig could be assigned to follow them. This technology has been out in the market for some time and continues to improve.

The company is very committed to this technology being part of the standard offering, along with the new lighting rig. This is not pursuing technology for its own sake but recognising that they would be foolish not to examine the tools available to the staging of complex productions as they develop.

“Technology itself is not an enemy of live performance: it is the application of technology, in whatever form, that is the measure,” remarked John. “That that measure will be an entirely subjective response, is a given.

“Generally, the use of any technology by any creative team is a choice. The idea that lanterns throughout the rig can, in principle, be individually tasked to track targets – performers, scenery and the like – is one I find attractive as a designer. The choice to use such technology would come down to how appropriate it is within any production concept and design aesthetic.”

This production of Aida lent itself to the idea of such technology – not just to notionally replace traditional front-of-house followspots but as a means of containing light within the stage house quite specifically to defined areas relative to the performers and their movements. There were scenes planned to have a front gauze which added to the appeal of having lanterns on stage being able to follow artists.

“This is not the place for a lengthy treatise on the merits or otherwise of the tracking technology,” mused John. “The hurdle to overcome was that there came a point in the technical rehearsals when it became obvious that we were asking too much in the time available.

“Having placed a significant reliance on the technology as a design component and to then have to turn around and do without it was disappointing. Not to speak of the significant redesign required in the latter stages of stage rehearsals.”

Those scenes where the technology behaved like it said on the box, as it were, were tantalising and not a little exciting. Being able to assign lanterns to follow artists based on their location; to assign such lanterns based on the most favourable angle of throw at any given moment was a great design asset.

“However, we were unable to reach a point of confident reliability and consistency with the technology and thus chose to go without on this occasion,” said John. “I have used tracking technology on other projects with great success. I look forward to developing its application in the future.”

OA offers a standard rig to all productions with a mixture of conventional (fixed) instruments and moving head lanterns. It has been introducing more moving head lanterns over the past five or so years to provide greater flexibility. Sydney Opera House has recently replaced all the conventional lanterns on the idiosyncratic Orchestra Bar with the Martin Mac Encore Performance WRM.

The choice to go with the WRM 3000K LED source (rather than the CRD 6000K LED) is presumably so that the lanterns will cohabit “better” with current opera and ballet standard rigs and their widespread use of conventional (incandescent) instruments.

OA has replaced its own previous mix of Martin MAC 2000 and VL 3000 in the standard rig with the MAC Encores, for uniformity. There is also a series of single Ayrton S25 Wildsuns rigged on the centre of each of the overhead lighting bars which John describes as a very useful and punchy workhorse.

“I additionally replaced further conventional instruments, for Aida, with eight Claypaky K-Eye K20 HCR,” John added.

“I enjoy their output, colour rendering and variable colour temperature. I have had to have an eye on the future standard rig, so attempted where I could to use the moving head instruments first. I found, too, the conventional lanterns struggled against the brightness and source characteristics of the LED screens. The MAC Encores also were lacking punch in some scenes (and with some colours) but nevertheless a versatile lantern.”

“I enjoy their output, colour rendering and variable colour temperature. I have had to have an eye on the future standard rig, so attempted where I could to use the moving head instruments first. I found, too, the conventional lanterns struggled against the brightness and source characteristics of the LED screens. The MAC Encores also were lacking punch in some scenes (and with some colours) but nevertheless a versatile lantern.”

Video cues were triggered from the ETC console with John adding that it all worked well, although he did have moments of confusion: initially it was thought that allocating any lighting cue number with a “.5” suffix would be enough to indicate a video cue only.

“This got a little unstuck and unwieldy when a video cue or a lighting cue moved in the stack relative to each other,” he said. “And, when the tracking technology was removed, there were many point cues required by the subsequent plot modifications. We will work to a better naming protocol next time.”

Traditionally there are no audio components to an opera but the Joan Sutherland Theatre has an unusual pit configuration with a very small opening which means you don’t get the fullness out of the orchestra. As a result some of the music is amplified, especially the instruments towards the back of the pit, to bring it out.

The theatre utilises the new Vivace electroacoustic reverb system.

“Basically each of the instruments are mic’ed and the feed goes into the Vivace box where in a 3D space you can say where these elements are,” explained Adrian. “Vivace then works out the reverb time and the arrival time of each of those instruments and feeds it to 160 loudspeakers.

It makes it sound like it’s coming from the pit whilst enhancing the reverb in the room. With it on, you’d never know but turn it off you’d notice it immediately.”

OA will present three digital productions in Sydney next year, and the first will be seen in Melbourne in 2020. The 2019 season of Madame Butterfly, Anna Bolena and a new piece based on Brett Whitely will also feature a full moving light rig.

This article first appeared in the September 2018 edition of CX Magazine – in print and online. CX Magazine is Australia and New Zealand’s only publication dedicated to entertainment technology news and issues. Read all editions for free or search our archive www.cxnetwork.com.au

© CX Media

Subscribe

Published monthly since 1991, our famous AV industry magazine is free for download or pay for print. Subscribers also receive CX News, our free weekly email with the latest industry news and jobs.