News

27 Oct 2017

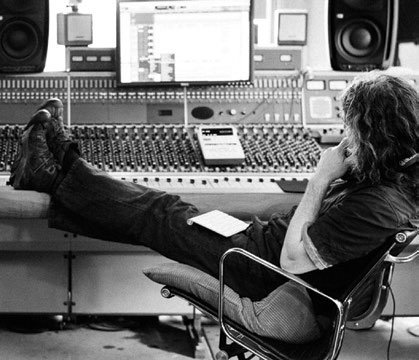

Studio: Listen Here – The Parallel Universe

Subscribe to CX E-News

REGULARS

Parallel compression is neither complicated nor scary, and it’s one of the most important tools in a mix engineer’s arsenal. With the world seemingly obsessed with heavily slammed digital mixes it’s crucial for mix engineers – whether they like it or not – to compress audio signals to unprecedented levels. Here’s how.

By Andy Stewart.

No matter how much is written about it or how often the enlightened try to impart their wisdom, compression remains a concept baffling to engineers of all persuasions and levels of experience. Some prefer to avoid it at all costs rather than get it wrong, such is their level of anxiety when faced with those dreaded knobs – attack and release.

But to avoid compression altogether in this day and age is a big mistake, arguably one of the biggest you can make. Without it, most mixes simply wouldn’t compete a damn in the modern world.

The only way to achieve relatively ‘loud’ mixes is to compress sounds all the way down the line: individual tracks, groups and mix buses in combination. It’s unavoidable. If you don’t you’ll leave the mastering engineer no choice but to somehow find 20+dB of dynamic range reduction to make your mix comparable to the millions of songs competing for listeners. By the time this has been achieved, some mixes will sound nothing like they did going in.

THE COMPRESSION LOOP

Parallel compression is another way to reduce the dynamic range of your mixes that’s altogether different from compressing individual channels, groups or the mix bus ‘from the top down’. But even more so than compression, parallel compression ratchets

up the fear of gain reduction in nervous minds to a whole new level of angst.

Compression feeding into compression? For some, it’s a concept just too far-fetched and scary to comprehend let alone deploy in a mix. But it needn’t be like this.

Actually parallel compression is easy, and a fantastic way for the feint hearted to get to grips with their compression demons once and for all. It’s also relatively forgiving for the simple reason that the settings you establish on a parallel compressor only work on a ‘submix’ of the music, rather than directly on the main output signal. Let me explain.

GROUND-UP POWER & EXCITEMENT

A stereo mix that includes a parallel submix (sometimes called a sidechain) of any combination of instruments can often achieve a ‘louder’, less dynamic yet more exiting mix outcome than ones that don’t.

Setting up a parallel mix is easy – it’s essentially no different to establishing an effects send/return, and we all understand how they work. Simply choose a stereo send via an auxillary output and feed whatever ingredients you like into a stereo compressor. The idea here being that you generally give the signals feeding into this compressor a bit of a hiding. Don’t be shy or timid with it now; you want the sound of the music through this parallel compressor to sound pretty outrageous. If you’re working on a song that needs attitude, this is where you’re going to find it. And sometimes conventional settings don’t matter so much; compression artefacts are welcome here!

Now return the output of this compressor back into your console on a stereo fader (or two mono faders). That’s it, you’re done. Simple as that. And people think parallel compression is hard?

All you do now is push the fader up and down until you like the effect of your more outrageously compressed signal mixing back into the stereo mix bus output. In this sense the parallel mix compressor behaves just like another instrument – more fader adds more attitude etc – only this one is all about filling the mix up with density, excitement, spatial definition and power without things getting appreciably louder.

Depending on the compressor’s tone – all compressors have them – good parallel compression will add strength to your mix, bringing it to life in ways you couldn’t imagine crafting solely with ‘top down’ compressors or equalisation.

What I love most about parallel compression, even when it’s being fed the full gamut of instruments, is that you can simultaneously add excitement and attitude to the stereo mix whilst controlling the dynamic. It’s the perfect panacea for dull, murky or flabby mixes that otherwise refuse to come to life. Trying to achieve this outcome solely with ‘top down’ compression often has the opposite effect. Things start to sound dull, flattened and less impactful because the compressor is working hardest on the loudest signals.

What I love most about parallel compression, even when it’s being fed the full gamut of instruments, is that you can simultaneously add excitement and attitude to the stereo mix whilst controlling the dynamic. It’s the perfect panacea for dull, murky or flabby mixes that otherwise refuse to come to life. Trying to achieve this outcome solely with ‘top down’ compression often has the opposite effect. Things start to sound dull, flattened and less impactful because the compressor is working hardest on the loudest signals.

With parallel compression you can imbue your mix with excitement from the ground up, adding power and sustain to things like snares, clarity and bombast to room ambiences, and density to sounds hidden just behind the transients of the music. The transient clarity of instruments remains mostly unaffected because you’re essentially leaving them alone, only now they’re not so far above the rest of the audio content because you’ve pushed more of that up from beneath.

Parallel compression has multiple two-fold benefits: you get clarity and power, apparent dynamism from compression, depth perception from dynamic range reduction, sustain and strength without turning things up, and that’s just for starters. For newcomers to the process, parallel compression is like a magic show. Things happen that you didn’t expect, and some of the benefits are counter-intuitive, most notably that power, clarity and depth perception are all achieved by flattening the dynamic range. Crazy.

Now I know all this preaching doesn’t necessarily convince anyone to go forth and patch in a parallel compressor every time they mix, and I concede that we’ve heard this all before. But while this might sound complicated and esoteric, I assure you it isn’t. Some engineers like to maintain a smokescreen around this technique because it makes them look clever, but in some ways parallel compression is easier that finessing a mix bus compressor on its own.

So if you can find a way to dispense with the notion that parallel compression isn’t for you because it’s too complicated or only for commercial rock records, it’s then simply a matter of giving it a go to see what affect it will have on your track.

CHOOSING THE INGREDIENTS

The question then is simply what to add to the parallel mix bus. The best way to begin your new life with parallel compression is by not thinking too much about it. Let the music tell you what it needs, and by that I mean, start with everything in, push the parallel compressor’s fader return up and just listen to its affect on the music. If something sounds much better with the parallel compressor pushed up, then great, leave it in. Conversely, if a sound in your parallel return makes an instrument seem too distorted, shrill or loud, either back it off in the send mix or ditch it from the send altogether. It won’t take you long to realise what works and what doesn’t, and before you know it you’ll be an expert.

As with every aspect of audio mixing, it’s not about having all the answers before you delve into a new technique, it’s about having the courage to dive in and see what happens. Getting it wrong leads to getting it right. Listening is the real trick and being convinced that something sounds better is the only true test of whether something is required or not.

Andy Stewart owns and operates The Mill in the hills of Bass Coast in Victoria. He’s happy to respond to any pleas for recording or mixing help… contact him at: andy@themillstudio.com.au

This article first appeared in the print edition of CX Magazine October 2017, pp.60-61.

CX Magazine is Australia and New Zealand’s only publication dedicated to entertainment technology news and issues. Read all editions for free or search our archive for news, tech-tips and products www.cxnetwork.com.au

Subscribe

Published monthly since 1991, our famous AV industry magazine is free for download or pay for print. Subscribers also receive CX News, our free weekly email with the latest industry news and jobs.