News

22 Oct 2021

The Gaffa Tapes: Support act to the meat raffle

Subscribe to CX E-News

“The way the music died”

Every musician and technician has at least one support act disaster story, but you know you’ve hit rock bottom when you’ve become the support act to the meat raffle.

MIDI was a major breakthrough for solo and duo acts during the latter part of the 1980s. Its emergence coincided with the decline of live band venues, which morphed into dedicated gaming establishments where MIDI performers would play second fiddle to meat raffles and poker machines.

Prior to MIDI (Musical Instrument Digital Interface), the only viable music backing for solo and duo acts was the humble cassette tape, which played off pitch; and good backing music was limited and very expensive.

MIDI was a steep learning curve for me, an anachronism from an analogue world. But even today’s digital music seems simplistic compared to the complex world of MIDI with its labyrinthine network of connections that linked my Roland MC-300 micro composer, Roland D5 keyboard, and Yamaha SPX-90 multi-effects processor. I should note that akin to some half-witted antic from a Dumb and Dumber flick, I did lug the D5 synth, which I didn’t play, out to my first few gigs purely to access its sound samples, unaware that Roland had a neat little U-220 rack mount sound module on the market.

With all this innovative equipment I was wary from the onset of being accused of some sort of technical chicanery. So, to legitimise my guitar playing, I augmented my 50s/60s repertoire with numbers from The Shadows complete with a Hank B. Marvin type echo triggered by MIDI from the Yamaha SPX-90. One of the forgotten gems of these tiny MIDI files was they could message sound modules and effects units to turn on and off instrument and vocal effects such as vocal harmonies, echoes and reverbs.

MIDI is one of the industry’s survivors. Today, it’s mostly used in the studio, but since digital music hadn’t quite evolved back then, it was a breakthrough. You could store around 20 MIDI song files on a 3.5” 1.44 MB floppy disc. MIDI files are similar to text files, which just send messages telling a sound module or effects module what samples or effects to play.

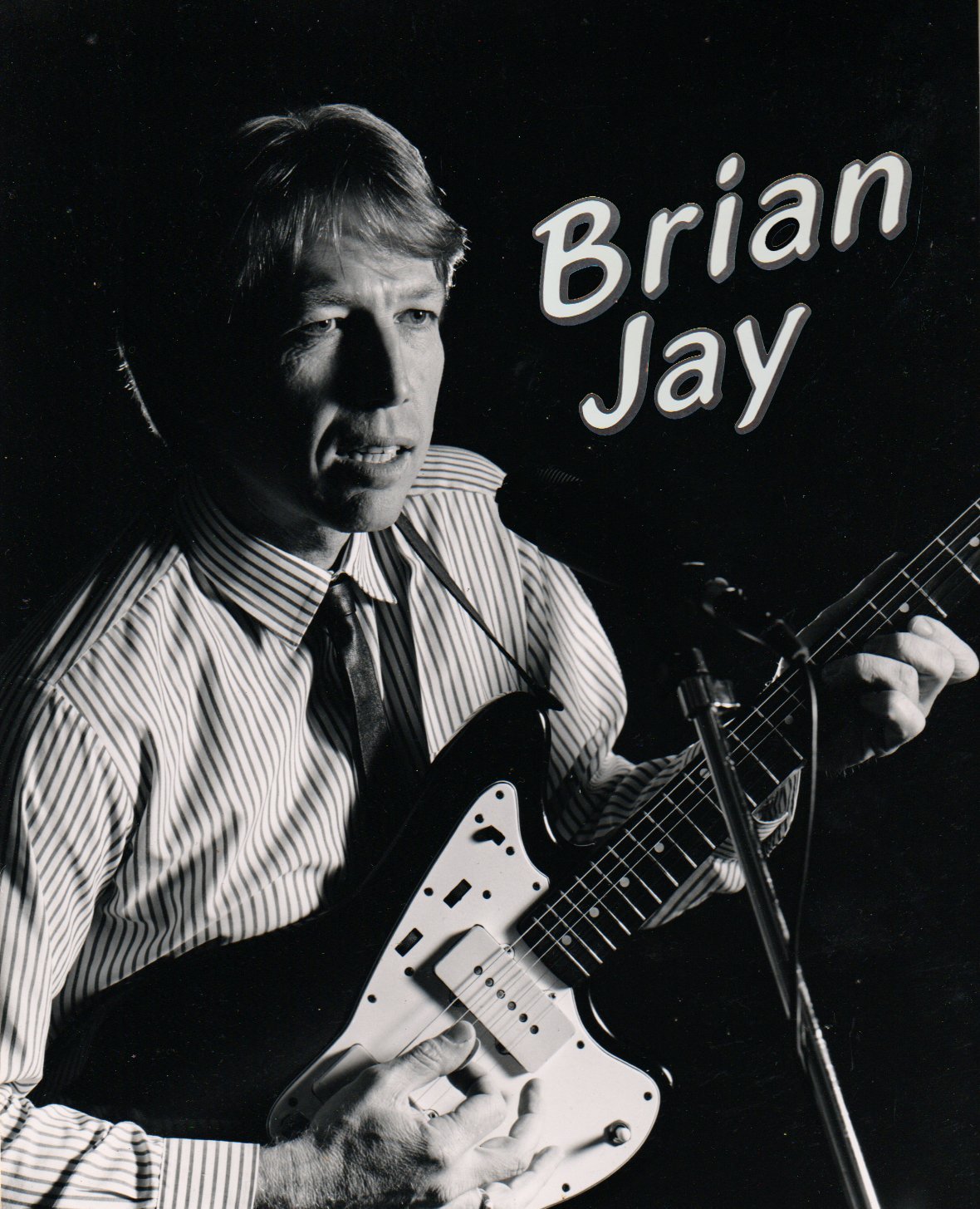

And so, armed with the latest advances in music technology and my not-so-scintillating stage name, Brian Jay, I re-entered the world of live performance. How could I have envisaged that in just a couple of years I’d be playing at an inner-city club devoid of patrons on a Saturday night, amidst empty tables with half-eaten schnitzels and spilled drinks, watching some passed-out punter’s cigarette burn down to his lips?

I don’t recall having too many absorbing conversations in those smoke-filled arenas where the punters seemed more stimulated by the music emanating from the poker machines than from my offerings. However, I do recall a bizarre conversation when an inebriated Elvis aficionado called me over to theorise his hero’s demise. He alleged that Elvis’ doctor was a compulsive gambler who gave the King a lethal injection because he couldn’t pay back money that Elvis had loaned him. Then he added, “And you know what? I don’t even believe he’s dead.”

I did play to packed houses, but patrons were either there for the meat raffle or some other attraction. And it wasn’t unusual to hear “Number twenty-seven to the snack bar” resonate over the club’s ceiling speakers during a performance.

In one bizarre engagement at the Balmain Leagues Club, I had to compete in real time with Trivia Night. Whilst I was belting out, “I’m a walking in the rain,” from Del Shannon’s Runaway, the trivia host would be shouting brainteasers on his microphone like, “Which Russian novelist wrote The Gulag Archipelago?”

I grew to accept my role as a side-act to the meat raffle, but it was difficult not to become misanthropic watching punters buying reels of meat raffle tickets that were sold for as low as ten cents each. Ten dollars got them one hundred shots at a meat tray, and I’d watch them robotically advance to collect their booty, which was as good as guaranteed given the abundance of meat tray prizes. I never heard so much as a cheer or a yahoo or any joy whatsoever, just a protracted procession of expectant winners.

The realisation soon sank in that those 70s support acts, where our bands played for free with the worst possible sound mix and light show, might not have been all that bad.

As dispiriting as being the benchwarmer for the meat raffle was, the real behemoth was the Monster Raffle. I arrived at the Botany RSL Club one evening in 1991 to find the entire width of the stage lined with prizes. Everything from bicycles to brush cutters, musical instruments to microwave ovens, food hampers to footballs, all stacked to the ceiling.

I set up behind the prizes, grabbed a beer and waited for the raffle to commence, and the prizes to clear. My scheduled time to go on came and went but the Monster Raffle prizes remained. The club manager approached me. “Hey, Brian, you’re supposed to be on.”

“But the entire front of the stage is stacked to the ceiling with prizes; they won’t see me,” I pleaded.

I very rarely spoke to audiences, but at the end of my set, totally unseen behind the Monster Raffle prizes, I couldn’t resist. I went to the front of the stage and made an announcement: “Thank you ladies and gentlemen. You’re just about to have your club’s Monster Raffle. Now when you come up and collect your prizes, just be aware that all the band equipment behind the prizes is mine.” Not a single chuckle emanated from the audience. I made a mental note to reconsider a career in stand-up comedy. Relaxing with a beer after my set, I noticed two patrons intently staring at me. One of them approached, “Don’t worry,” he said rather abrasively, “We won’t take your equipment.”

My last one-man-band gig was New Year’s Eve 1992. I’d come out of retirement (for want of a phrase) because NYE gigs, unlike the typical $200 fee, paid $500. It was a club with lots of stairs, so I decided to only load in one speaker. Mindful of years of being asked to turn down, sometimes to a level below the volume of the poker machine music, I didn’t see this as an issue. I set up in the lounge area and quietly went about playing to my regular audience of empty tables and chairs. Some twenty metres away at the bar NYE revellers were getting liquored up for their midnight countdown caterwauling. I noticed the club manager approaching. He delivered a request rarely, if ever, heard by MIDI performers: “Could you turn up the music please, we can’t hear it at the bar.”

Subscribe

Published monthly since 1991, our famous AV industry magazine is free for download or pay for print. Subscribers also receive CX News, our free weekly email with the latest industry news and jobs.