THE GAFFA TAPES

23 Oct 2025

SOMETHING OLD, SOMETHING NEW

Subscribe to CX E-News

Snippets from the archives of a bygone era

In a world fixated on the digital and AI evolutions, other significant changes that have impacted our live music and recording industries have been relegated to footnotes in history. And in the midst of exponential technical changes, there is still a devout group of players clinging to traditional live and recording techniques, while there are also aspects of our industry that haven’t really changed all that much.

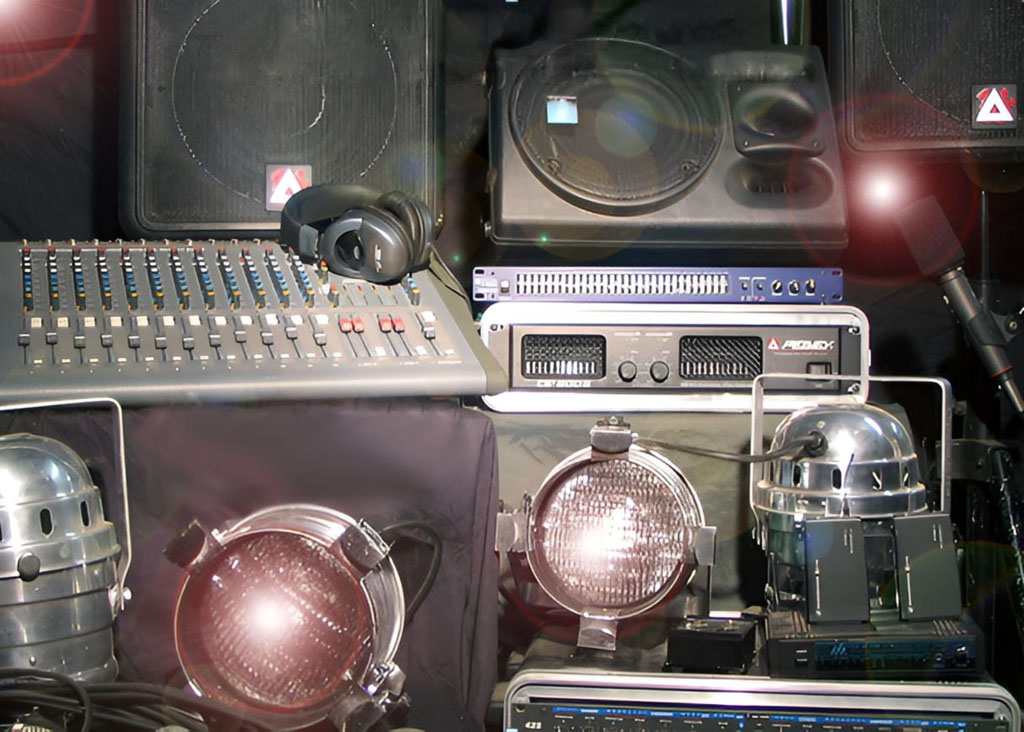

So, did it make sense to mothball my 90s PA system in the garage all those years ago in the hope that my son would someday use it in live music performances? Well, after a 17-year waiting period, Russell gave his first performance in August of this year at a school event in a trendy Newcastle City nightclub. I particularly noticed that in this changing world, the PA wasn’t all that different from my 90s system gathering dust in the garage: speakers on stands, wired and wireless microphones, an analogue mixer, graphics and reverb effects, etcetera. While some performers clipped their smart phones onto a microphone stand, I didn’t see how this enhanced the various performances or was all that revolutionary compared to a sheet of paper gaffa-taped to the microphone stand or taped to the stage floor. Yes, the LED lights, which have become ubiquitous in less than two decades, added a cool touch, and I would rather be crutching sheep than regressing to the power draw and heat problems associated with tungsten lighting. Thus, I have owned my LED studio lighting for many years now.

People new to the industry might feel that LEDs have been around for eons, but in a 2011 interview with Diesel (Mark Lizotte), he told me how he was trying to come to terms with LEDs. “I’m trying to get used to LEDs. I’m not sure where I am with them emotionally. I’m not sure if I love them yet. I’m like, ‘Ok, this is the way it’s going,’ and I do love the fact that they’re so much lighter. I can really appreciate that the crew loves them because there’s no changing of bulbs. The components last a hundred years or something (laughs). But they’re more expensive, and it’s a different kind of light.

I’ve noticed, looking down at my fretboard, it throws these weird little shadows. I’ve had to say a few times, ‘Just be careful where these lights are focused.’”

People new to the industry might also not be aware that the introduction of poker machines in hotels in the 90s had a far more devastating effect on the pub rock industry than any technical innovation. Profit margins from pokies were so high that venues that were once entertainment hubs became stylised casinos virtually overnight when governments changed the rules and allowed the flood of slot machines into the pubs. Previously, most bands in the 70s and 80s could pick up the phone, ring around the pubs and eventually get a gig. But after that window of opportunity was closed with the onset of the gambling bug, the only major viable venues were clubs, and you had little chance of working in a licensed club if you didn’t have an agent. This was an era when a lot of musicians moved into home studio productions, a lot of which have now morphed into podcasts and online video productions.

A bit of research and sneak trip over to Julius Grafton’s recently purchased Sydney PA Hire website confirmed my suspicions that things hadn’t changed all that much in the hire department either: a digital mixer here and there, some Bluetooth, some LED lighting, but nothing that would confuse a Baby Boomer that had just emerged from a time warp. Interestingly, a recent press release from ENTECH, Julius’ former exhibition enterprise, stated that half of all attendees were, “now identifying video as a core technology of interest.” Undeniably, this swing has been ushered in by the evolution of the internet, where video hosting sites like YouTube and TikTok have made marketing and communications an even playing field and a favourite of consumers.

One of the major changes in sound reinforcement came in the late 80s when the industry was moving away from horn-loaded speaker enclosures like JBL 4560s and W-bins, to composite PA systems like the Meyer Sound system that Ian Richardson introduced to Australia in the early 80s. More modular ‘point source’ systems started to appear on the scene, like the EAW KF850s introduced by Norwest; these were the predecessors of the line arrays of the 90s and onwards. These new systems saw the ultimate demise of the huge speaker stacks employed by major touring acts. Not everyone could afford to buy or even hire composite PA systems, and a lot of pub rock bands clung to the large conventional enclosures, which were no longer needed after the pokies decimated the pub rock scene.

In 1983 I was contracted to outfit an American nightclub just off the U.S. Air Force base in the Philippines. Along with the 4560s, which they already had in the country, I decided to introduce the double W-bins. I found the plans in a Balmain library, and the librarian allowed me to make a Xerox copy for 5 cents. The local Filipino JBL dealer, Lin Gomez, built the W-bins for me, and I installed them in my first nightclub engagement. However, Lin told me that JBL was no longer specifying W-bins for their speakers; instead, the recommended cabinets for their subs were 4520 J-bins and also 455OA bins, not folded horn W-bins. I later worked in a nightclub where Lin Gomez had installed 4520 J-bins, and after hearing the front-loaded bass push and sub-bass pumping out of the J curve, I was no longer enamoured with W-bins. Paradoxically, because our nightclub was so successful, Lin Gomez was inundated with orders to manufacture the inferior W-bins, and I was eventually approached by one of his competitors, who offered me a huge sum of money for the plans, which had cost me 5 cents at the Balmain library. It was an offer I couldn’t refuse. When I returned to Australia in 1986, I had a pair of J-bins manufactured for a club I was working for, and they sounded great, but large enclosures were already on the wane.

While the Beatles are credited with creating the foremost musical change in modern history, I never considered that they changed the very fabric of popular music. Moreover, they shook up an industry that had been churning out manufactured music by stylised acts that used professional songwriters and backing musicians, something akin to what has happened to the current wave of mass-produced music tailored to a marketable structure. The Beatles gave budding musicians a more humanised, grass-roots prototype of the makeup of a band.

Both Norman Smith, the Beatles’ first sound engineer, and Glynn Johns, the Beatles’ recording engineer on the Get Back/Let It Be recordings, laboured to change stringent studio techniques to produce live-sounding recordings. Norman Smith dared to move the acoustic panels (gobos) that divided the instruments and vocalists so he could emulate the sound of a live band. He dared to place microphones in positions that were frowned upon by studio executives. The Beatles’ producer George Martin also broke from tradition when he made all the Beatles the focal point, instead of an individual singer backed by the other musicians in the band. Despite Glynn Johns’ persistence at producing live-sounding studio recordings, his mixes were all rejected by the Beatles.

Johns recently strongly criticised modern recording techniques, and he sent shockwaves through the recording industry when he made derogatory comments about SSL mixing consoles, such as those installed at Abbey Road Studios. “I think they’re diabolical. I hate the sound of them; they’re overly complicated, unnecessarily so,” he said.

I hadn’t seen the Let It Be film since I sat in an Auckland picture theatre in 1970, but Peter Jackson’s 2021 Get Back release illustrated that some things hadn’t really changed all that much. The bane of my life has long been themed 60s and 70s parties where people dress like freaks, thinking that’s the way we all dressed back then. The Get Back footage showed that you could walk down the street today with the same hairstyle and the same attire that the Beatles wore in the doco, and you wouldn’t get a second glance. You will also see the same instruments, like Fender amps, Ludwig drums, and Fender and Rickenbacker guitars, used today in recording studios. The control room with its outdated mixing console and tape machines is a bit of a giveaway in the Get Back flick, but Glynn Johns, who has mixed sound and produced groups including the Rolling Stones and Led Zeppelin, maintains that he still uses the same dinosaur mixing consoles and edits analogue recordings on quarter-inch tape at 15 IPS.

Over the years I have embraced some technological changes and rejected others, but have I embraced the digital and AI evolution? Well, I do all my recording on a multichannel DAW via my Yamaha AG06 mixer, which is a little gem. It’s not purely an analogue mixer; it’s a hybrid digital/analogue mixer with high-quality preamps and a USB audio interface.

I use a digital NLE (non linear editor) for my videos, and I have a Veo 3 subscription to generate AI video clips to give some of my old songs a new lease of life.

One of the main reasons I transitioned from PA hire to installation and entertainment management in the mid-80s was to avoid the heavy lugging (and, of course, the unruly drunken punters). It makes sense to have powered composite speaker enclosures rather than lugging heavy amp racks and monstrous bins up several flights of stairs in venues that don’t have elevators. But apart from that, if I get the chance to mix my son’s future band in a live venue, I’ll most certainly go with my existing analogue mixer and other equipment that hasn’t changed all that much in the past 30 years.

But would it make sense to regress to inferior antiquated equipment? I’d rather be a goat herder in Siberia than go back to tape for recording, and how far back would I go to embrace an antiquated analogue mixing console? The answer is, not too far because there have been major improvements in microphone pre-amplifiers and EQ. We all loved Jands equipment in the 70s and 80s, and the company has transitioned into a distributor of high-end audio, video, and lighting technologies. But that doesn’t mean I’m out scouting for another of my once-owned 1978 Jands 12-channel JM5 mixing consoles.

Subscribe

Published monthly since 1991, our famous AV industry magazine is free for download or pay for print. Subscribers also receive CX News, our free weekly email with the latest industry news and jobs.