LISTEN HERE

10 Jul 2023

LAYERS OF MULTIPLICITY

Subscribe to CX E-News

When you listen to your favourite recordings by other artists what do you hear? If you’re anything like me, what you perceive is often vastly different to the average listener, particularly when it comes to production techniques like double- and triple-tracking, harmonies and layering. But not always. Sometimes we’re in the dark like everyone else.

Let’s say you’re about to embark on a production that needs to sound big, wide and spectacular. You’ve already decided that a minimalist approach is not the way to go and you’re determined to push the production’s sonic boundaries. What’s the worst thing you can do in that circumstance that will almost certainly doom the production to failure?

Stall mid-process.

Far too many of us baulk at the prospect of generating excessive channel counts in our productions, even when our imagination suggests otherwise. Sometimes it’s because we’ve heard too many old-school producers quip that excessive numbers of tracks infers indecisiveness, or a lack of ideas. At other times we find ourselves working with a client who’s easily spooked by the apparent confusion generated by multiple recordings of anything.

In either circumstance, the moment things get a little tricky or confusing the temptation’s always there to throw your hands in the air and pull the pin on the process. What you’re left with then is a product that’s half-baked; caught in no-man’s-land between a desire to expand into more complex territory or shrink back to a place of relative safety.

But a more insidious problem then arises. We remain subconsciously tethered to our original concept and fall back on tried and trusted tools of engagement, stereo reverbs, delays, synths and mic techniques, to generate the ‘width and depth’ that our original approach would have more ambitiously provided.

There’s still scope for large-scale mix outcomes using only these techniques, of course, but often the results are a pale imitation of your original concept.

Stay The Course

So, before you embark on multi-tracking a single part, layering vocal harmonies, or building width into a production via a multiplicity of performances, you need to reaffirm your commitment to the approach, remembering that it’s not always easy to pull off, invariably breeds doubt mid-process, and inevitably involves more time and effort than more modest alternatives might require.

Moreover, before you hit the ‘go’ button on any kind of sonic endeavour like this it pays to be clear about what it is you’re trying to achieve. It’s imprudent to dive headlong into a complex recording process if you’re unclear about the sonic aims or even the methods you intend to use to achieve them. Without a plan or process in mind there’s every chance you’ll end up in the weeds and need a machete to hack your way out.

And if you don’t have a plan, what then?

Learn to develop one, just like you would any other production or engineering technique.

The Planning Permit

One way to develop a more planned approach to your future large-scale productions is to analyse some of the techniques employed by others.

As a first exercise, try analysing a song you listen to constantly, focussing in on how each component of the instrumentation is represented in the final mix.

Start by writing down all the component parts on a large sheet of paper over the course of several repeated listens. Once you’re satisfied you have them documented, start listening to each sound individually (not the song as a whole) asking yourself how each sound has been recorded and mixed. You may not get this exactly right, of course; it’s hard deciphering the nuts and bolts of a sound from the outside, but give it your best shot regardless.

Listen critically. Don’t jump to conclusions. Write down specifics about each sound, not vague adjectives like ‘warm’ or ‘big’.

Where is the sound placed? Is it panned? Is it a single instrument or five? Is it buried low in the mix or leading the arrangement? Is it filtered? Is it broken up into several harmonic pieces? Is it comprised of a large cluster of instruments? Is it chorusing or pitchy?

Listen for details, clues or any giveaways that might help reveal the technique behind the sound.

When you apply your exceptional powers of audio analysis and deduction to a familiar track, one thing that might surprise you is that the song is not quite the construction you thought it was. Some of your favourite ingredients aren’t quite what you’d assumed them to be – and yet you thought you knew the song so well! All this time you’ve heard a particular sound a certain way and subconsciously come to a bunch of erroneous conclusions, never noticing your mistakes until now.

These errors might seem harmless enough, or even irrelevant. But when you’re in the business of crafting song productions for a living, mixing complex arrangements, or writing and recording, it matters a great deal.

Any misinformed sense of ‘knowing’ that you squirrel away in that brain of yours can later prove damaging to your own process, sometimes taking years to extricate, especially if they’re long-held beliefs.

And nothing sends you up the garden path faster than a self-imposed myth.

An example of this might be a sound in your favourite track that you’d always assumed was a stereo recording of a single performance. But now, when you listen more critically with pen and paper in hand, lo and behold!, turns out it’s comprised of multiple performances of a single arranged part. There might be two, three or even more performances in there where you’d always assumed there was one!

In the same song, that especially wide stereo synth part you’ve grown so fond of over the years is not a single stereo track at all, but rather a single chord featuring two or three inversions, and multiple panned sounds all with slight pitch variations. What makes this sound so massive is not the fancy synth patch you’d always assumed it to be, but rather microscopic variations between several hitherto hidden individual performances.

Details like this are often lost on the average listener, but not you, not ever! So how have these production techniques slipped past your ear unnoticed until now?

Critical analysis, not casual listening.

These ‘component parts’ are harder to determine sometimes from an outsider’s perspective, even when you’re an accomplished producer. But if you’re in the business of making music for a living, it pays to be aware of how certain sounds are constructed by others, particularly if they influence your own musical aesthetic.

Micro Idiosyncracies

There are a million ways to layer sounds for scale, width and depth in a production; far too many to even begin to touch on here.

But it helps to understand why all these layers, multiple performances, audio clusters (call them what you will), have the effect on your ear that they do. They all have something in common; micro-idiosyncrasies, ‘fingerprints’, if you will, that combine together to make a sound huge.

Every performance has its own unique fingerprint, and individual recordings need only vary microscopically to provide stereo width, complexity, chorusing and scale that no reverb or echo can authentically mimic. Exploiting this characteristic of an individual sound is what then allows your next production to sound big. Frankly, orchestras have been doing this for centuries! Shall we tell them they’ve been wrong all along; that you really only need one violin, a viola, a timpani and some reverb to sound big?

So, forget the nay-sayers; they mostly have no idea what they’re talking about anyway. Allow your next big production to take full advantage of the innate sense of scale that layered sounds can create. Try planning the piece on that same large sheet of paper you used earlier, only this time you’re going to imagine the arrangement in detail yourself.

What sounds do you want to appear close and intimate in the final mix? What sounds do you want to use to frame the song and provide width, and what will establish the sense of ‘horizon’; giving it the scale you desire?

Remember, the layering of sounds is all about their differences, microscopic or otherwise, so you don’t necessarily want to make them all perfect. You may record 15 individual human performances on an acoustic instrument, or you might generate 10 different sounds from one MIDI file using different patches and micro adjustments to pitch. You may like the slight imperfections exposed when two individual, hard-panned performances come together to create one massive sound that appears to flutter in the stereo image. Conversely, when there’s a dozen performances all panned in almost mono up the back of the song, you may want them to be as tightly performed as possible, so as to create scale but not mayhem. The choice is ultimately yours.

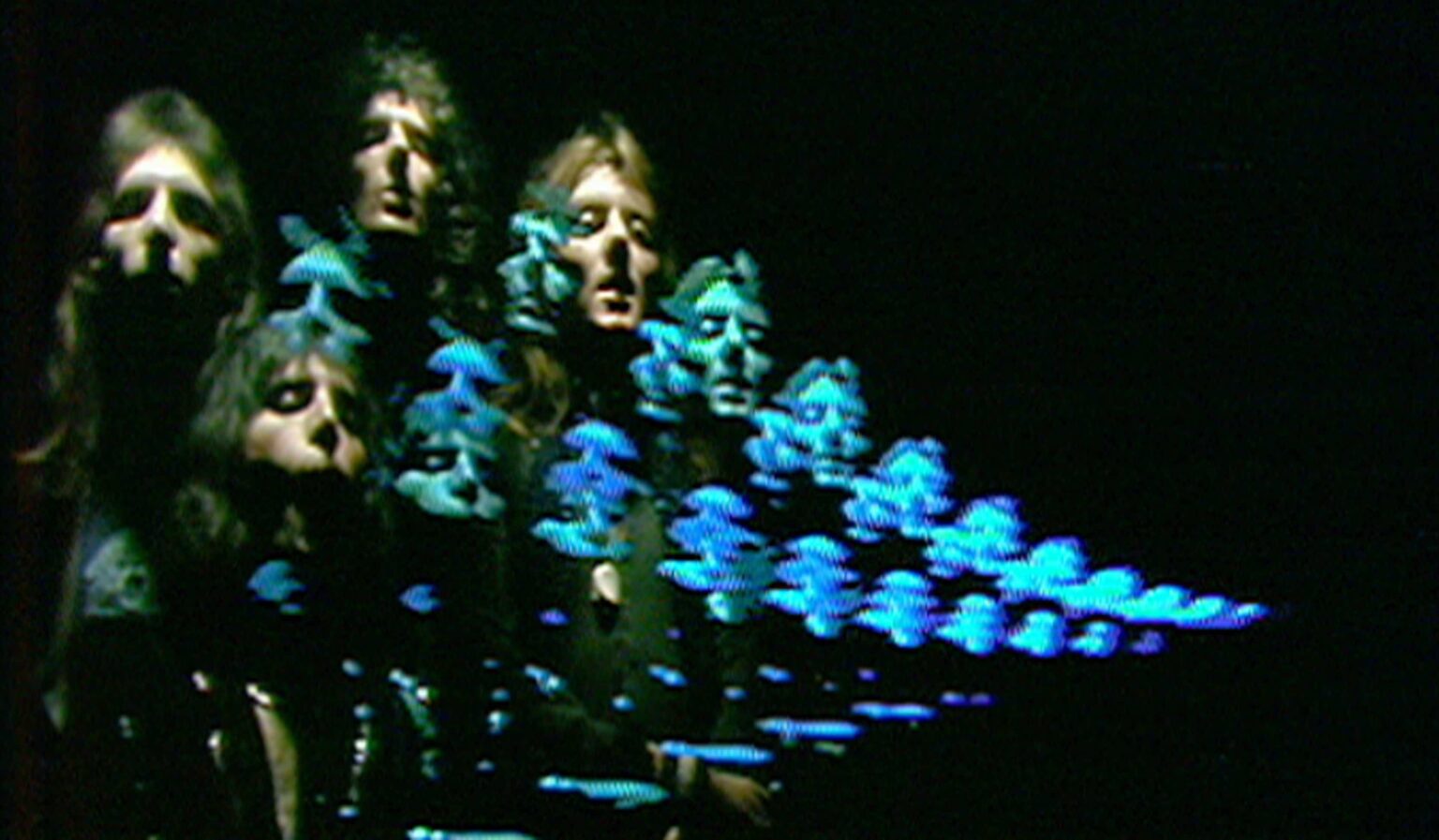

Regardless of how you build the components of your new epic track, don’t let the purists who say ‘less is more’ influence your thinking too much – sometimes that advice is garbage; a rule based on a theory that applies to nothing in particular. If Bohemian Rhapsody had been made following a minimalist philosophy, what would the outcome have been? Would any of us even know the song?

Andy Stewart owns and operates The Mill studio in Victoria, a world-class production, mixing and mastering facility. He’s happy to respond to any pleas for pro audio help.

Contact him at: andy@themill.net.au or visit: www.themillstudio.com.au

Subscribe

Published monthly since 1991, our famous AV industry magazine is free for download or pay for print. Subscribers also receive CX News, our free weekly email with the latest industry news and jobs.