News

30 Jan 2020

Stereo Typical

Subscribe to CX E-News

Stereo Typical

In the world between our two speakers, there’s a universe of sounds we can craft, and countless techniques we can deploy to trick our brains into thinking we’re floating in three-dimensional space. Unfortunately, most people leave decisions about the stereo imagery in their mix ’til after the recording phase is over.

This represents a huge missed opportunity to create unique recordings. It also demands more of the mix process, and leans more heavily on the use of artificial space.

Why not just record cool stereo images instead?

Stereo pairs – when it comes to microphones, we love them! So much so that some of us revere the ‘matched pair’ like a two-headed deity, particularly when sequential serial numbers are involved. Two Neumann U67s with serial numbers 006 and 007… it’s as if I’d died and gone to heaven.

Matched pairs can capture beautifully balanced stereo images, as everyone who records audio can attest. For some instruments, or groups of players, a matched stereo pair represents an awesome recording tool.

But something happens to our brain when we associate stereo pairs too closely with stereo images. Are they the same thing? Can you even record stereo properly without a matching pair of microphones? Well, depending on your point of view, and what you mean by stereo, abso-bloody-lutely!

A/B Or Not A/B – That Is The Question

One of the least explored aspects of the modern-day recording process is the way a ‘stereo image’ is captured.

Most people associate this concept directly with only one approach: two microphones, preferably of the same make, placed symmetrically in front of an audio source, recorded to two tracks of audio, and panned left and right on the console to reveal a wide, balanced, phase coherent stereo image.

Ninety nine times out of a hundred, this is exactly what’s recorded. In the case of a solo instrument, this source is invariably placed dead centre in the image. Now the big question is simply, why? Why put every audio source dead centre in a recording’s stereo image, particularly when the arrangement is a complex one?

There are a couple of obvious answers we must touch on here first, before we take a hard left turn off this conventional road into a vastly more creative and exploratory way of thinking about stereo.

Firstly and foremost, this conventional miking technique is about phase coherence. By placing the source dead centre of the image, and by using two matched microphones positioned in some version of a coincident pair, we capture a clear and stable image that’s often wider than the alternative: a mono microphone positioned in virtually the same ‘piece of air’.

Secondly, when there are very few instruments in an arrangement, perhaps even only one or two, any extra width and space can be vital to the final mix. Indeed, the mix can often simply be the unadorned sound of this high quality stereo image.

But often, and particularly once an arrangement gets busy, this extra width is often lost, barely audible amongst the barrage of other sounds vying for your attention. The subtle soundstage captured during the recording is all but consumed by the complex nature of the final arrangement and mix.

More often than not this inevitably leads mix engineers to do what some recording engineers can barely acknowledge: they pan (or worse, maliciously damage) the stereo images to exaggerate their perspectives.

Sometimes a mix engineer will affect only one side, turning the prescribed second channel into a radically different, reverberant and distorted echo of the original recording. At other times they will simply ditch one channel altogether, to avoid the common situation where 10 stereo recordings panned left and right combine to create a giant, unfocussed lump in the phantom centre of the image.

I could go on about this for 10 pages… seriously.

But instead, let’s look at ways we can be more creative in our recording adventures. The key to unlocking this more ambitious, exploratory mindset is to think ahead!

1: The Look-Ahead Uninhibitor

Look ahead into the production of a song, or piece of music, and ask yourself (particularly if you’re reaching for a coincident pair at the time) what do I predict this sound to ultimately be, and how big is the final arrangement likely to get?

Now if it’s a blockbuster rock song, with lots of instruments, vocals, and a predictably large-scale mix, you probably know this from the outset: the final stereo mix is going to be big!

This is precisely the time to think differently about stereo. You are not serving the individual sounds here; you’re serving the mix. To that end, 25 overdubbed instruments recorded symmetrically in X/Y will not automatically produce a large-scale final stereo mix. On the contrary, they may make it a blurry, lumpy mess, particularly if every source is in the centre!

Similarly, a pair of super close guitar amp mics will only really provide you with tonal options (not a bad thing), and a pair of acoustic guitar mics in X/Y might end up doing squat in the final mix (and maybe, upon reflection you’d be wiser to record two individual mono takes of acoustic).

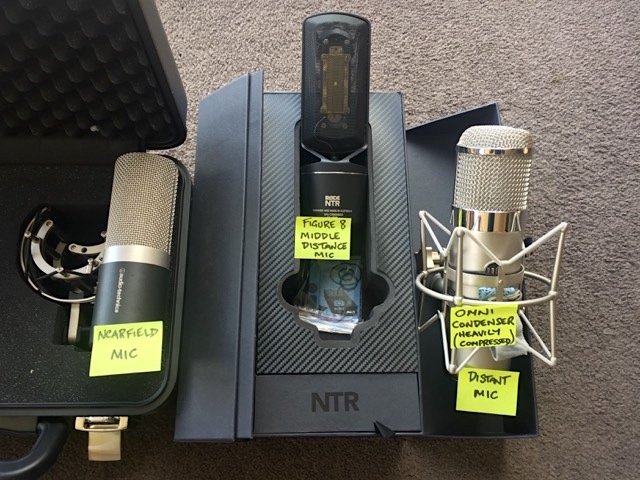

Why not instead think in more exploratory terms: put a great mic on the guitar amp (if that’s what you’re recording), a second across the room 20 feet away, and a third (yes, a third – stereo recordings aren’t, by definition, only two mics – you could use six if you like!) placed as far away from the source as you can, to capture ambience unique to that space.

The more you go for unique sound capture during the recording phase, the more spectacular and individual the final mix will be.

2: Informed Decisions

The further into the session you get, the clearer your perspective presumably becomes on the role of a particular overdub. For instance, when you’re recording a big backing vocal, and it’s the 75th sound in an arrangement, it’s likely being recorded for a specific purpose.

Sometime it pays to put these sorts of vocals into a new space, not just yet another mono or stereo image. Here you might choose to place the artist quite asymmetrically in a stereo image.

To do this, simply setup a conventional stereo pair, but do not put the artist dead centre in that image. Get them to move around in the space until it sounds cool to your adventurous ears. When panned hard left and right, you get all the air of the recording, but the source positions itself left or right to some degree or other, depending on where they’re standing.

When you start exploring this technique, a whole universe of sounds opens up to you.

The trick is to consider phase here. The more identical an audio source sounds in two (or more) microphones, the more potential there is for phase issues to crop up. But that’s okay, we’re looking to exaggerate our stereo perspective anyway, and the best way to do this is to have our mics sound different, not virtually identical.

By placing mics further apart, using different makes and models, different compression settings, and different polar patterns, we’re going to end up with recorded audio that’s sufficiently different in its waveform that phase applies less and less critically.

By the time two mics are recorded, where one is shoved against an amp and the other is across the room in figure-eight with its null pointing back at the source, and a compression ratio of 20:1, the chances of the two affecting one another’s phase is effectively zero.

3: Space Exploration

The bigger a production gets, the more scope there is for an engineer to think ‘mono’ and ‘space’, rather than left and right stereo. This sounds nuts in some respects, but it’s true. Big, complex song arrangements and mixes require definition and contrast, and things placed close and central in that final stereo image need all the help they can get to be heard.

So there’s no point insisting on recording in X/Y over and over again for every stereo overdub – particularly the more incidental ones – because at some point this approach serves virtually no purpose.

Instead, go for good mono sources occasionally, and record the space conceptually as a separate component of the tracking. This can be a mono mic, or several mics all positioned differently, all designed to serve the final mix in more creative ways.

4: All Bets Are Off

Finally, when it comes to stereo images there are no rules defining what’s good or bad, apart from phase. If two mics are horribly out of phase, you’re better off with one; otherwise your mix will change radically in mono, mostly to its detriment.

Beyond that, how stereo is achieved is all about your decision-making process: do I love the sound, does it serve the production in context, and is it phase coherent? It might be the main vocal you’re recording, or the 100th overdub on the session – it doesn’t matter.

Explore the space, ditch conventionality, and exaggerate the differences between your mics. You will never look back once you do.

.

CX Magazine – Dec 2019 Entertainment technology news and issues for Australia and New Zealand – in print and free online www.cxnetwork.com.au

© CX Media

Subscribe

Published monthly since 1991, our famous AV industry magazine is free for download or pay for print. Subscribers also receive CX News, our free weekly email with the latest industry news and jobs.