THE GAFFA TAPES

22 Sep 2025

A Hard Day’s Byte from MIDI to AI

Subscribe to CX E-News

Snippets from the archives of a bygone era

My foray into the digital world wasn’t via a PC or a digital mixing console; it was via a MIDI (Musical Instrument Digital Interface) sequencer at a time when Microsoft was still using MS-DOS as an operating system.

It’s been 40 years since MIDI empowered solo and duo live performers along with studio producers, but in no way is it a spent technology. Many AI music generation tools output certain results as MIDI files. This is so they can still point to sampled audio files for further editing using MIDI. While the two technologies complement each other, they are fundamentally different. MIDI allows various musical and digital devices to communicate with each other. AI uses algorithms that can analyse data, learn patterns, and then generate new content. Thus, AI has become a very useful tool that I regularly use for track separation and replacing vocals (mostly my own) with AI’s digital performers.

My introduction to MIDI was when a former band mate, guitarist/vocalist Joey D, bought a Roland MC-500 for his one-man-band performances. When I eventually purchased the MC-500’s baby brother, the MC-300, for my own one-man-band show, Joey D came over and taught me how to use it. Using a sequencing device that could talk to both my U-220 rack-mount sound module and my Yamaha SPX-90 multi-effects processor was a surreal experience. MIDI was a pure sound, although guitar samples weren’t that good because of their complexity, and vocal samples were virtually nonexistent except for ‘oohs’ and ‘aahs’. That didn’t matter, because we performed the guitar and vocal parts ourselves. AI can often misinterpret input during analysis and leave digital artefacts, whereas MIDI doesn’t suffer from such misunderstandings.

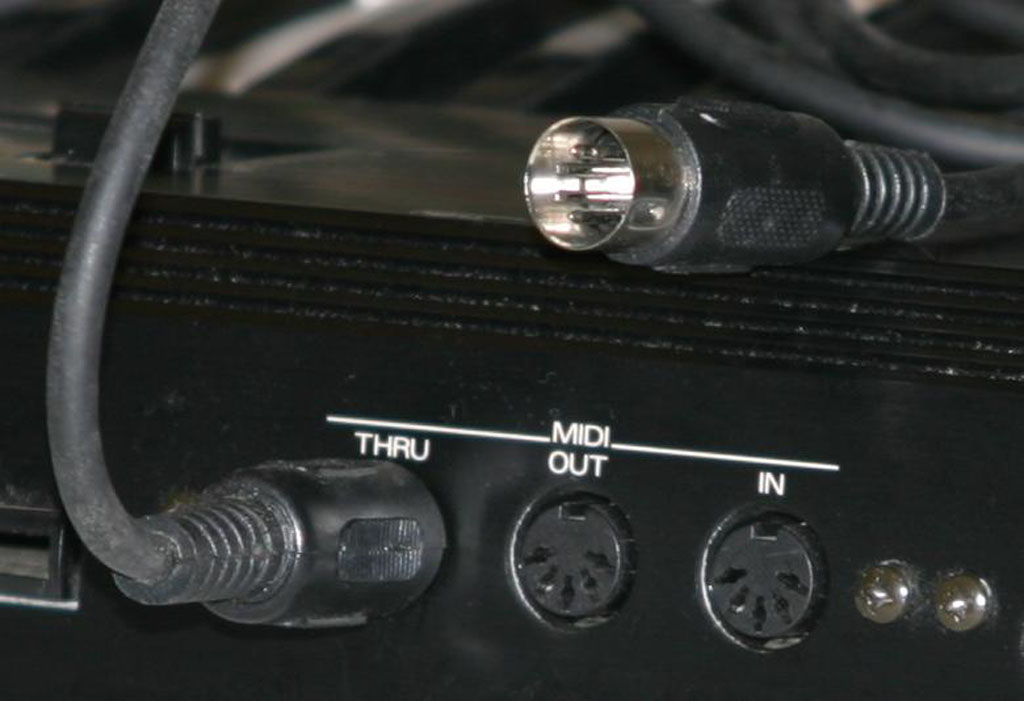

Since MP3 became the standard for music files in the mid-90s, there have been two full generations that may not have experienced the power of MIDI. Put simply, MIDI files use a binary code, which is a kind of text file that was stored on a 1.44MB floppy disc for the Roland sequencers. These files pointed to samples stored in a sound module. All MIDI-compatible devices had a MIDI Thru port, through which you could connect other devices that could communicate with the MIDI files. For example, my sequencer was connected to a U-220 rack-mount sound module, which would play all the sampled instruments, drums, keyboards, bass, brass, strings, etc. Connecting a MIDI cable via the Thru port to my Yamaha SPX-90 multi-effects processor could add effects like echo, reverb, and chorus, along with very nice-sounding vocal harmonies. MIDI also had powerful control changes, which were CC messages that in real time could turn effects on and off or lower volume. For instance, if you wanted to add a harmony to your voice in the chorus of a song, a simple control message in the MIDI file could turn this on and off during the performance. Likewise, a control message on the humble MIDI file could turn on and off vocal effects such as reverb and echo in real time.

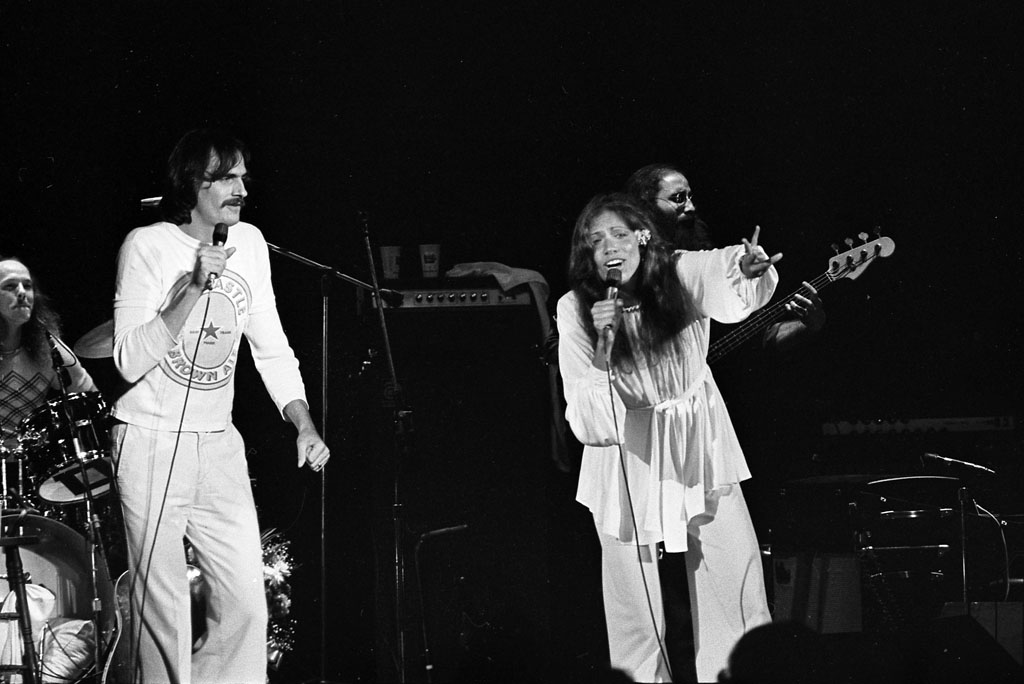

MIDI provides many of the components and guidelines for digital music, while AI can be the architect that analyses and uses those components in artificially intelligent ways. My prime use of AI has been to advance my penchant for writing parody songs, ‘sung to the tune of’ existing songs. I wrote parodies during my teenage years, but my first parody to be played on the radio was in the late 80s. This occurred when Sydney radio station 2Day FM organised a competition inviting listeners to create a parody song about their suburb.

I was a Bankstown boy, living in its satellite suburb of Yagoona, which was where the first McDonald’s in Australia opened. The suburb was also noted for the RSPCA’s Animal Shelter, and former PM Paul Keating went to my school, De La Salle College Bankstown. My parody, which was hand-written lyrics mailed to the radio station ‘sung to the tune’ of Under the Boardwalk, was chosen and played on air.

We had the first McDonald’s in Australia, now I call that prestige,

So our claim to fame besides the dog pound is a Big Mac with cheese,

We raised Paul Keating, who raised our taxes and fees,

It’s a shame we can’t blame him for the rise in our social disease.

I was selling broadcast equipment to radio stations at the time, so I visited 2Day FM, and the chief engineer was kind enough to give me a copy of the tape, which was produced in their studios using live musicians, vocalists, and backing vocalists. Backing tapes had to be performed by professional musicians in those days, and they were expensive, but the rise of MIDI made music backing a commodity, and with the arrival of the MP3 file, these could then be made into audio files. I began using MIDI-converted MP3 files for backing music, and legendary radio presenter Ian MacRae was giving me airplay. The limitations of singing the parodies were that I was limited to male vocalised songs and, of course, my vocal range. AI solved this problem, but not without its flaws.

Moises and Lalal.ai are well-established AI-powered tools that can split songs into individual components, including vocals, drums, and bass, to create remixes and different arrangements. This may not seem like an innovation given that music backing services like Karaoke Version have had inexpensive, professionally arranged melodies with professional singers on separate tracks for eons. However, when writing parodies, you want to get as close to the original singer and backing music as possible. By splitting the original composition, you then have the original voice in the parody; this is especially effective for high and sustained notes that might have otherwise sounded a bit croaky. The AI voice is then steered into following the original singer’s voice. You can even sing a song by a female artist in falsetto, and the AI female digital performer will interpret this as a female singer and produce a female vocal. Something that I found very interesting was how AI mimicked technical vocal qualities; while most AI performers had better tone and timbre qualities, they still very closely copied my phrasing and expressiveness; in fact, the results often still sounded similar to my voicing but with improved vocal qualities.

The separation of music tracks by AI is called stem separation, and the individual tracks become the stems. I used stems for my community radio station sweepers, jingles, and air checks. There was a lot of talk about AI methodology when the remaining Beatles released Now and Then in 2023. The reality was that no AI machine learning (ML) of Lennon’s voice was used; it was simply stem separation followed by some tweaking in the studio.

I’ve talked to many artists who believe that AI will eventually take over music composition, but my perspective is quite different. Of course, we are going to see the music conglomerates and major music streamers push the AI envelope, and it wouldn’t take much for them to climb above their current wave of garden-variety music. Moreover, it would be more of a cost-saving venture than a major shift in music creation. I’m not currently aware of any mind- blowing hits or classics that are a result of AI composition, and satirical comments about the AI-generated group, The Velvet Sundown, included, “I wanted to go to their concert, but it was a ‘hard drive’.”

Regardless of my personal preferences and predictions, music producers are increasingly navigating to AI music production software; even the enormously popular ChatGPT, which is primarily a conversational chatbot, can write song lyrics and music and produce results as a multichannel MIDI file if requested. However, some of the classic modern songs come from the writer’s own life experiences or individual journeys of other people known explicitly to the writer. For example, Carly Simon’s ‘You’re So Vain’ was a personal account from her real-life experiences with an unnamed person. James Taylor’s hit ‘Fire and Rain’ was about the tragic suicide of his childhood friend Suzanne Schnerr at 19 years of age. ‘Hey Jude’ was McCartney’s lament about a lost Julian Lennon trying to deal with the divorce of his parents.

Lennon’s song ‘Julia’ is about his mother, and ‘Dear Prudence’ was Lennon’s observations of Mia Farrow’s withdrawn sister, Prudence, during their sojourn in India with the Maharishi Mahesh Yogi.

You could, of course, feed the known facts of personal experiences into AI, but it cannot write from its own emotions; it can only draw on stored data banks and use complex algorithms. It has a lack of genuine understanding and experience, and because it learns from existing data, it becomes predictable and lacks empathy and originality.

It’s kind of paradoxical that gifted writers are fearful of an artificial intelligence that has been widely criticised for churning out overly padded, soulless garbage. To be fair, I asked an AI chatbot what it thought about these scathing comments. It agreed.

Main Picture is, in fact, an AI generated image

Subscribe

Published monthly since 1991, our famous AV industry magazine is free for download or pay for print. Subscribers also receive CX News, our free weekly email with the latest industry news and jobs.