News

2 Jun 2020

A Potted History of Remote Control

Subscribe to CX E-News

Our device is over there. But we are over here. We could walk over and activate it. Or we could wave a magic wand and, hey presto, control it from a distance.

Evolution of the remote control

Teleoperation as a general concept has been around since the late 19th century. In 1898, Nikola Tesla debuted the Teleautomaton,

a radio wave controlled miniature boat.

Onboard antennae and a receiver allowed unconnected control of speed, direction and some lights. Given that few were even aware that radio waves existed at the time, it must have created quite a stir.

Of course, that came off the back of Guglielmo Marconi’s pioneering work in radiotelegraphy a few years earlier in 1894-5.

In 1903, Leonardo Torres Quevedo used the quaintly titled Hertzian (radio) waves to demonstrate control of an electric tricycle and boat using his Telekine system. The patent describes it thus:

“It consists of a telegraph system, without wires, whose receiver sets the position of a switch that switches on a servomotor, operating any mechanism.”

This was a big leap at the time. Even more importantly, he devised a pulse system of codewords that overcame the binary limitations of contemporary telegraphy.

Over the next half century or so, most effort in this field was directed to controlling military vehicles and weapons remotely. Although there had been many DIY control experiments, none were common.

In 1939, Philco released their ‘Mystery Control’ wireless handset, allowing remote wireless control of radio and radio-phono sets. It’s a weird looking unit but gave a hint of the future.

It was really in the 1950s that these technologies hit the consumer market and became more ubiquitous. The booms in post WW2 television and leisure time were major drivers in kicking this off.

The first TV remote control to hit the mainstream was the Zenith Radio Corporation’s ‘Lazy Bone’ in 1950. Tethered by a cable to the TV, the Lazy Bone controller allowed viewers to remain seated while changing channels and volume.

Tired of complaints about people tripping over the cord, Zenith came up with the ‘Flash-matic’ remote in 1955.

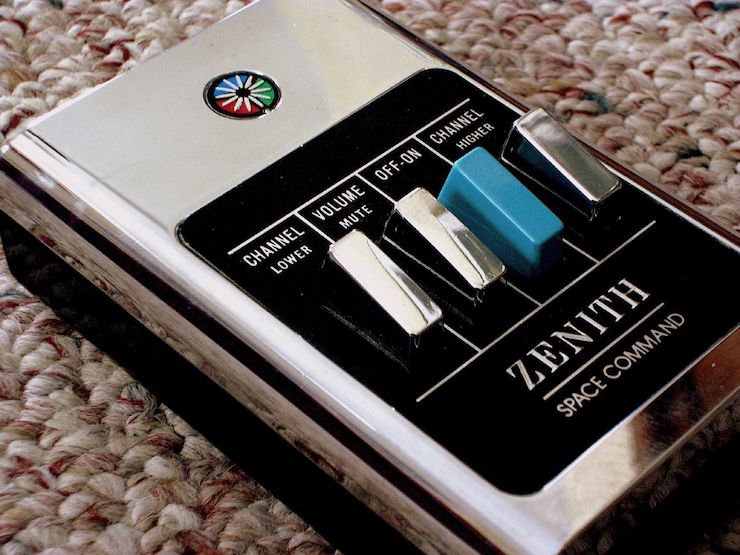

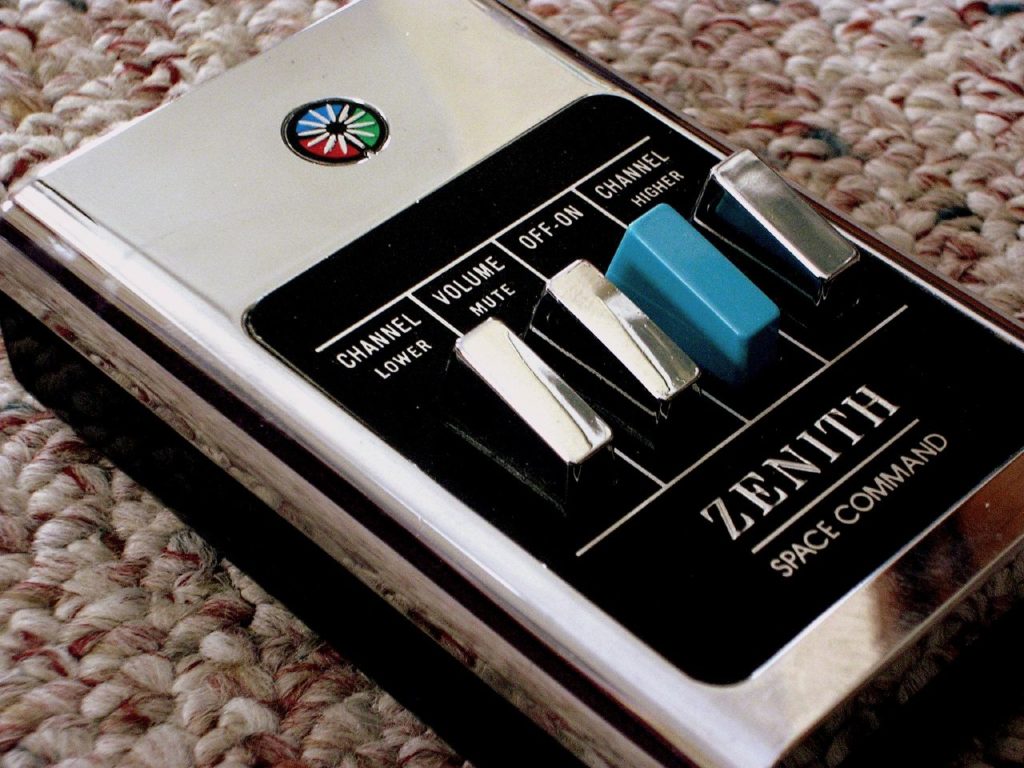

It shone light from a cool looking ‘gun’ towards photocell receptors in each corner of the screen but had serious crosstalk problems on sunny days, so 1956 saw the release of the ‘Zenith Space Command’.

These conveyed instructions to the receiver using ultrasonic sounds generated by the internal striking of aluminium rods. The buttons clicked which explains the ‘Clicker’ terminology used by folks older than me.

From “Television: TV in the Antenna Age”, SFO Museum

This ultrasonic technology type was dominant with appliance manufacturers until the early 1980s, when infrared controllers came to the fore.

IR is cheap and functional but it has serious limitations being mono-directional and requiring line-of-sight. 2-way communication methods such as RF, more ultrasonic (voice, movement), Bluetooth, and now WiFi have also been used to control our shiny toys and essentials.

Beyond TV

Since the 80s, the humble control wands have multiplied like the generations of gadgets they come with and infiltrated our domestic existence.

Starting with a garage door opener, moving on to a wand for your HVAC control, then the myriad appliances in the home entertainment stack of doom, each with its own plastic clicker, it’s hard to get away without a pile of button drenched batons supposedly dedicated to making our life easier.

Instead, we end up with far too many choices to contend with and far less control. Consider the simple act of watching a show on the TV: use the grey remote to fire up the AV receiver, the white one to turn on the display, the small black one for the set-top box, back to the grey one for volume, and then surf with the black one.

And please don’t do any of that in the wrong sequence, lest the precarious balance of non-interactive devices be upset and the whole mess needs resetting.

Over time, and with the promise of a Jetsons existence, more solutions have evolved to try and curb the confusion. AV control systems started commercially but soon found their way into high end homes, replacing the jumble of handsets with a singular interface.

At the lower end of the technical food chain, the universal remote came into existence. A cheaper way to consolidate control of multiple devices into one terminal, many still required a PhD to setup.

I dearly remember my Dad (then in his late 60s) configuring one for his 90-year-old mum: three remotes combined to one but still way too many choices for my otherwise cognitively sharp grandmother.

This was solved with a stiff cardboard cover that only exposed the necessary three buttons. Even career engineers can do hacks!

Why are they so ugly and confusing?

Unfortunately, I also hold engineers responsible for the button jumble that we have inherited. Just because a device can perform 374 functions doesn’t mean it should have that many options on the control interface.

Have you ever used all the buttons on all your remotes? Unless you’ve sat there with an IR learner capturing codes for higher level control, probably not. And you probably never will.

Conversely, industrial design-led control products (such as the ‘fruit’ company) can be a bit too minimalist and may not allow the user the depth of control they require.

There is an artform to devising easy but powerful man-machine interfaces, enhancing the user experience rather than detracting from it. It is partly technical, partly emotional, partly psychological, and wholly arcane.

Further, there is no perfect solution as all devices and system configurations are as different as their users. The rise of personal home assistants has ushered in a new method of interface but they are not for everyone, particularly heavily accented people.

Phones and tablets are also fast becoming the control link to your electronica. It’s easy to download and configure an app and, bingo, control in your palm. It is much harder though to find and keep track of all the apps – somewhat like a digital version of the lounge room table clutter of yore.

Commerce and combat

Before the age of mass consumption exploded, most research on remote interfacing was conducted in the military and space spheres. From Torres Quevedo’s early torpedo control to all manner of Unmanned Undersea Vehicles (UUV) and Unmanned Aerial Vehicles (UAV) that we see today, vast sums of capital and ingenuity have been invested by states and corporations worldwide into machines without humans onboard.

UAVs have come a long way and we are now seeing them used for all sort of purposes. Once only the domain of secret military function, drones are now widely used across the civil spectrum. Each one with a person operating them from afar.

Commercially, remote control technologies have particularly assisted mining operations, from remote plotting and surveying to faraway controlled trucks and trains.

Agriculturally, many large stations now monitor distant water sources, fencing and sensors from afar, saving untold hours in the field. Big cropping concerns are getting into GPS controlled farm implements, maximising the efficiency of each pass.

Elevation mapping, asset inspections and funky stuff like vegetation measurement (NVDI & EVI) are becoming very useful to the switched-on farmer.

Back home again

GPS is another remotely achieved technology that now pervades our lives. It’s great for on the fly navigation but equally great for deep state intrusion. Leave it switched on and the internet knows where you are 24-7.

Plenty of countries are pandemic tracking people right now.

There are other examples of remote control in our daily lives. PCs and other computerised apparatus can be accessed at some distance. Many cameras now forgo a tethered shutter release cable and can be triggered by your phone app.

A fun one that I’ve omitted until now is Remotely Operated Vehicles (ROV). How many readers grew up with RC cars, boats and planes? How many still enjoy using them?

Less fun but more essential is remote surgery. This is especially prescient given our current distancing measures. Telehealth has been scoffed at by the bean counters for a considerable time but it is surging to the fore while we are forced into isolating in our bunkers.

Some context

OK, I’ll admit it – I was once an avowed Luddite. I’ve always used the minimum technology available and like to keep things simple.

Working with electronic devices for decades and directly employed in AV automation for nearly eight years, I was proud to NOT have any remote controls in my own home. After all, that was what I spent all day at work doing and I was more than happy to get off my nethers to change a channel on the TV.

I’ve since relented on that one, but (computers aside), a WiFi remote to the Raspberry Pi media server is as high-tech as it gets in our mud and straw house. Most devices here still require manual interaction!

What’s next?

With the ability to bring up the status of our install and touring rigs on our phones and control them from the other side of the world, who’s to say where remote control goes next.

My crystal ball is too cloudy to tell for sure but it will undoubtedly blow minds when it first launches – perhaps combining the tactile response of a hard button with the real-time feedback of bi-directional comms.

Let’s hope it has a good battery life…

Sending an email in 1984: www.youtube.com/watch?v=szdbKz5CyhA

Personal assistants and the Scottish accent: www.youtube.com/watch?v=XQCHoKAq9xA

CX Magazine – May 2020

LIGHTING | AUDIO | VIDEO | STAGING | INTEGRATION

Entertainment technology news and issues for Australia and New Zealand

– in print and free online www.cxnetwork.com.au

Image attributions:

Nikola Tesla

https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Bateau_t%C3%A9l%C3%A9commande_de_Nikola_Tesla_(mus%C3%A9e_de_Belgrade).jpg Boban Markovic / CC BY-SA (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/4.0)

Telekino

https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Telekino_receptor.JPG MdeVicente / CC0

1955 Zenith Flash-Matic

https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:1955_Zenith_Flash-Matic.jpg Edd Thomas from UK / CC BY (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/2.0)

Zenith Space Command (Lead)

https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Zenith_Space_Command.jpg Todd Ehlers / CC BY-SA (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/2.0)

SABA corded TV remote

https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:SABA-corded-TV-remote-left.jpg Gazebo / CC BY-SA (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/4.0)

© VCS Creative Publishing

Subscribe

Published monthly since 1991, our famous AV industry magazine is free for download or pay for print. Subscribers also receive CX News, our free weekly email with the latest industry news and jobs.