History

28 Sep 2020

Sydney Olympics, September 2000

Subscribe to CX E-News

Gold For The Production

Twenty years ago this month Sydney staged the biggest event yet seen in Australia and Connections Magazine was there with comprehensive coverage of the production. Some highlights from the October 2000 edition follow.

Olympics shine may be unbeatable

By Julius Grafton

Let’s score the Production. Gold for Sound, Lighting, Rigging, Flying, Wardrobe and Stage Management. Silver for the Cauldron. Bronze for the telecast vision, Gold for TV lighting and Audio. Australian ingenuity just got recognised worldwide!

If the Olympics is remembered for anything other than the sporting events, then the Opening and Closing Ceremonies are it. And how bold, how large, and how dangerous are these enormous shows?

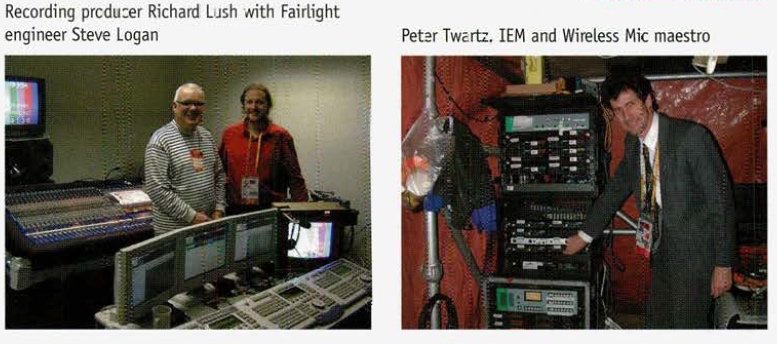

First, lets say hooray for the music. As Connections rightly reported last month, leading Producer Richard Lush spent a vast amount of time recording everything you heard on the night. Fairlight came good with a new Merlin, allowing hard disk editing and non linear access to everything.

At the Opening, as our coverage reveals, the best of either live or recorded were blended. The orchestra, playing live, were mic’ed – but what were you hearing? Our story inside reveals.

Spare a thought for the composers, unsung heroes that they are. Chong Lim excelled with his Nature segment. David Stanhope managed to make the Australian National Anthem sound like a new and exciting creation – while keeping it aligned with its traditional sound.

The audio, both live and telecast was virtually flawless. No mean undertaking, as the broadcast mix was done more than a kilometre away, out the back of the IBC.

Lighting was vibrant, set the mood, and punctuated the scene. It all appeared to work, it wasn’t overdone, and it is a tribute to the resources marshalled by Bytecraft and designed by John Rayment and Rohan Thornton.

The flying was breathtaking, both on TV and in the flesh. It pushed the boundaries, and as our story this month reveals, was almost done on a wing and a prayer as precious rehearsal time evaporated with high winds.

Genius was thick on the ground at Stadium Australia. Even the thing that momentarily stalled, the cauldron, astounded. Our story this issue shows you the construction and throws some light on what was almost a disaster.

We needed heroes, and now we have them. This should be a time when the Australian trait of cutting down the tall poppy is buried.

Tributes please, to Ric Birch, David Atkins and Morris Lyda. More tributes to Bytecraft and Norwest Productions – the live audio production firm, who were sadly ommitted from the printed program.

When talk turned to the Olympics at ENTECH back in March, we heard a few dark pathetic and miserable souls commenting snidely that these companies couldn’t possibly do a show like this.

These people live in a different Australia.

The most interesting thing of all is that it’s very unlikely anyone will ever stage a show so large again.

Cauldron almost kills resoundingly successful ceremony

By Julius Grafton

Here it is, the biggest idea of the Opening Ceremony, and with its final execution, possibly the best theatrical effect ever invented. But it nearly failed, and the failure would have been much more dramatic than first thought.

When the Olympic Flame left Greece, two custom made brass miners lamps were used to carry it. As the Torch Relay wound its way around Australia, the mother flame and backup were always nearby.

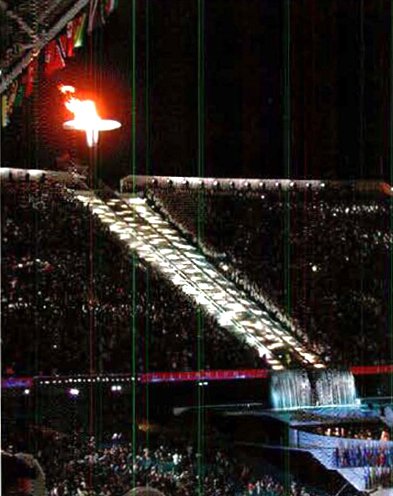

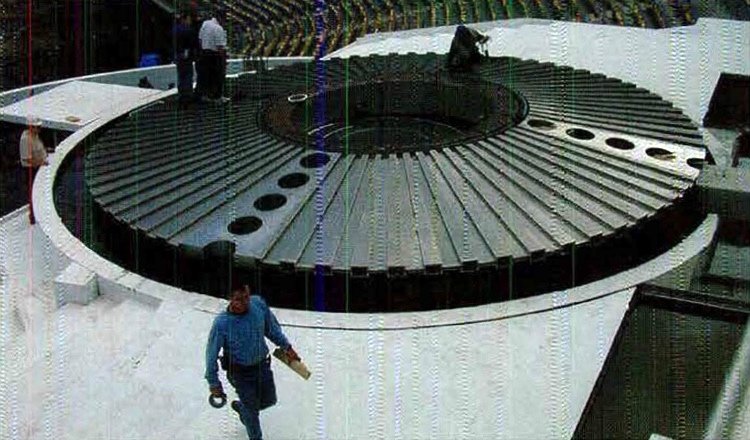

At the opening ceremony, the Cauldron made a spectacular and surprising debut, raising out of the pond around and above Cathy Freeman. The picture at top left shows the device lifted about a foot above the edge of the pool.

Fully lit and fast burning a lot of bottled gas and hydrogen on board, the Cauldron stalled at the cart (top right) when a limit switch malfunctioned. The talkback system was deadly quiet as the engineering crew manually confirmed all was correct before overriding the errant switch.

Some nervous minutes passed, the vision cut to startled torch bearers, and Cathy Freeman was instructed via in-ear monitors on how to look and what to do at this unplanned pause.

The soundtrack marched on, timecode unravelling towards the automatic cue for the fireworks which then went off early.

The Cauldron was slowly running out of gas.

Ric Birch says it had plenty left, but some crew claim it was actually failing as it finally came to rest and was hooked up to the mains. Unknown at the time, the mother flame and backup were missing,

presumed stolen.

It could have all gone dark…

Lighting the Biggest Show on Earth

As one of the most complex shows ever staged started, a small army of lighting crew quietly did their job, and the results stunned the world. John Grimshaw reports …

After an extremely hectic two week, leading up to the event, the night went went surprisingly well – only three lights were lost in that mammoth rig. However, the time leading up to the deadline was, according to Paul Rigby (Technical Manager), very stressful indeed.

One of the major problems they faced was that there was 258V coming out of the sockets.

Meeting with OCA and Energy Australia initially looked like there was nothing they could do about the problem. With the over-voltage, all of the followspots and space cannons were blowing circuits and seriously damaging themselves.

In addition, much of the other European equipment simply was not coping with the voltage. It reached a point where the German technicians here to supervise the equipment said that they would not let the cannons be used until the power was fixed.

Some arm-twisting was applied to Energy Australia – who had previously said they weren’t going to fix the problem. The result was that they sent a great deal of resources to re-tap a number of transformers off the 10,000V lines to the stadium.

Luckily, the work was completed (just) in time for plotting and rehearsing before the 15th. Another problem that was conquered by the opening was that the scrollers on the 4k wash lights were not behaving properly.

These teething problems could have been anything – the spurious voltage, the wind or heat in the stadium or even simple DMX issues. Hours were spent in the air on the truss looking at the problem and fault finding.

Experts were flown in, and slowly the scrollers were made to work.

To deal with the followspots, Lycian sent a technician to try and help – on the day of the opening.

In the end, there was probably a representative from every lighting manufacturer that supplied equipment just to make sure it all went smoothly.

It is very easy to understand Paul Rigby’s statement; “The two weeks leading up to the night were very stressful.”

Compliments must be paid to every technician on the ground and Bytecraft for the outstanding quality and the horrendous hours involved pulling this show off.

Despite the fact that there was some concern that the international make up of the team may lead to tensions, the professionalism of the entire group was continuous and impressive.

This is the first time Bytecraft have taken on a “Producers” role, looking after the entire requirements of the performance lighting as a “turnkey” operation.

They could not have chosen a bigger show to debut this new aspect to the company, but Steven Found (Bytecraft Director) has been extremely happy with the results. In fact, it will probably take the next month to reply to all of the emails he has received.

By all reports, everyone involved slept for three days once the show was done (were they dreaming of the accrued overtime?).

Athens sure has one hell of a show to follow.

When we asked John Rayment how he thought the show went, John replied in his typical (almost trademark) laconic style, “Oh I think it went well.” Although there is considerable understatement in this reply, Rayment went on to say that there were certainly things that he would have liked to have more time to work on.

“The task is to produce as much as you can.” In the two weeks they had to prepare, plot and rehearse, Rayment was able to create a living design that well complimented all of the other elements of the show. However, he is always looking for room to improve.

“If I achieved everything I wanted to do, the bar was not set high enough says Rayment. Would he do it again? The question was barely asked when he firmly replied, “Yes.”

Rayment likes to think he has come out of this show older and wiser. Next time, he would be able to head off a few more problems, and would choose to do a few things differently. In fact, his next opportunity to do it all again comes very quickly as he is lighting the ceremonies for the Paralympics.

In summing up the experience, Rayment only had one minor difficulty that could not be easily resolved. “I thought at times that the creating the lighting for the show was given a bit of a back seat. It (lighting) is not just the hardware or installation – it is the creation of pictures – painting with light.”

Rohan Thornton, lighting designer for the television audiences, was also quite happy with the final result. As has been reported in the general press, the various reactions worldwide were very complimentary. In particular, they had some good feedback from NBC, German television and a few other broadcasters.

Thornton comments that certainly a couple more days of preparation would have helped, but in the end they achieved what they set out to do. The biggest problem faced by the broadcast was the extreme contrast between bright and dark scenes.

Today’s broadcast quality cameras can cope with very little light, however it takes time for a camera operator to get picture corrected after a big lux change.

Thornton was very happy that very early on money and resources were allocated to audience lighting – the scenic backdrop for the television audience. Ultimately, the opening was always going to be judged by TV pictures, and this is also how the world will remember the ceremony.

Because of the size of the event, so much of the show had to be created from scratch using the skills of the team involved. “There was certainly no folder from last year to look up,” says Thornton.”The final success of the opening ceremony is a tribute to all involved.”

And what a team that was. Three lighting designers (John Rayment, Rowan Thornton and Trudy Dalgleish) and the very capable management team from Bytecraft (including Stephen Found, Paul Rigby, Rowan Trundle, Durham Ritchie, Nikkitas Comos, Edward Fardell and David Storie), all involved moved heaven and earth to make sure the show worked.

Even manufacturers and suppliers came to the party, helping when required to make the show happen. These different international partners included, Strand Lighting, High End Systems and Procon – all supplying equipment and/or labour at greatly reduced cost.

To the various technicians, riggers, desk and spot operators, volunteers and others (including the poor buggers running cables for eight weeks) you should be proud to have been involved in such a successful show.

Connections also previewed the LX component of The Games in the September edition. [Extract here]

Audio For The Biggest Show on Earth

Conceived, designed and executed by Australians, the Sydney Olympics Opening Ceremony was the largest show yet held on earth. It’s going to be hard to match, as Julius Grafton discovers …

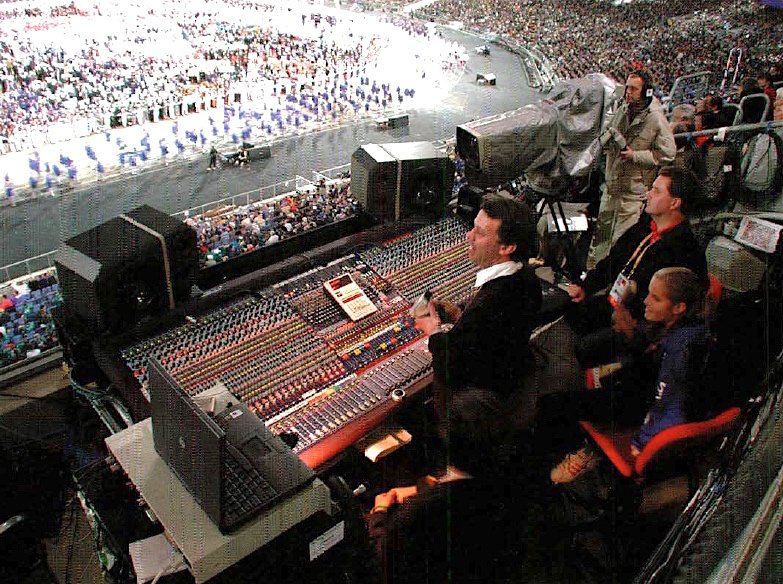

Audio for the worlds biggest show required some of the world’s smartest people. It was a duel effort between broadcast and live, with the two teams co-operating from day one.

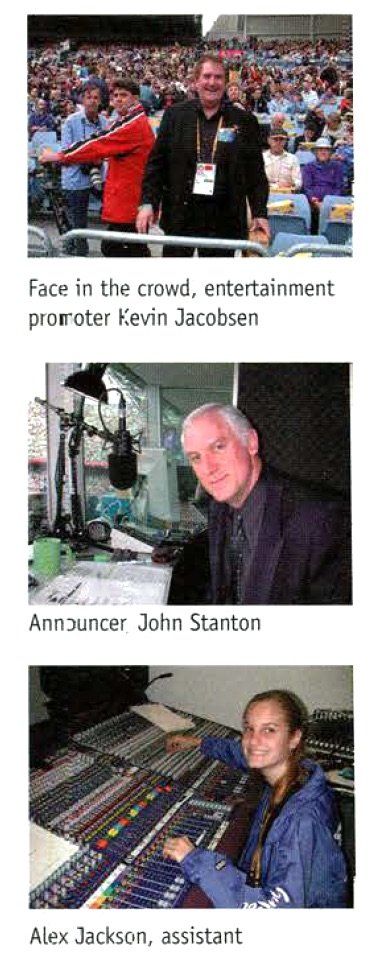

“Its not always like that, the PA company just come in and do what they want sometimes,” said Audio Director Bruce Jackson.

Audio Producer Colin Stevenson agrees, and having designed and supervised the mix of the show for the 3.1 billion people on this world, he should know. “Its often tortured. People who know their stuff, like Bruce, are a delight to work with.”

Live audio was supplied by Norwest Productions of Sydney whose already excellent reputation has skyrocketed as a result. Broadcast audio was originated by SOBO. SOBO supplied all other broadcasters with output, including ambient mixes. This produced some interesting situations; host broadcasters added commentary.

“The hard part of our job was that SOBO were only set up to do effects and ambience originally, then we were to produce all audio for the biggest show on earth! All the international broadcasters took all our content.”

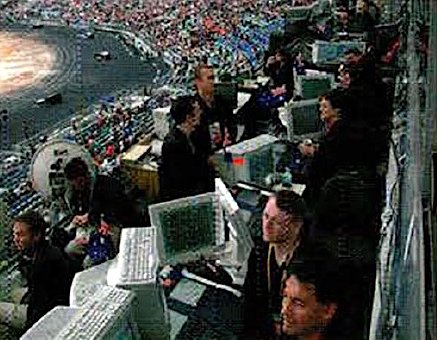

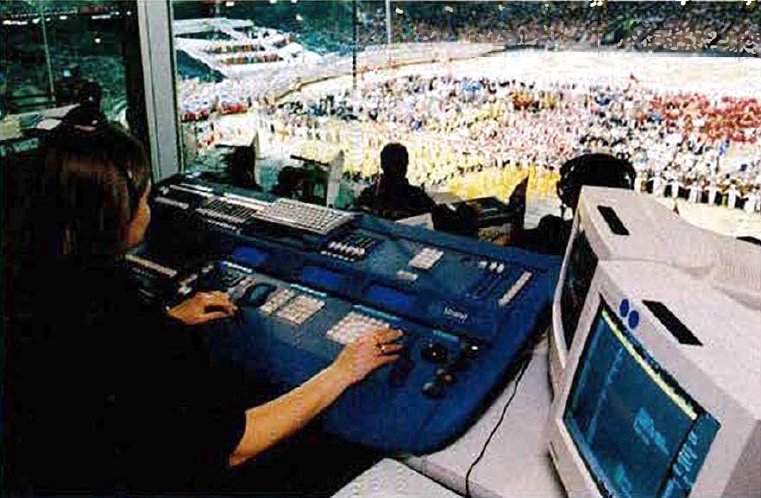

The broadcast mixing position was more than a kilometre from the source. It was over the road from the Olympic Stadium, down a hill, across a car park, and inside the massive International Broadcast Centre (Connections, August page 72 – read extract here, which also includes a Games preview article ’10 MILLION watts’.

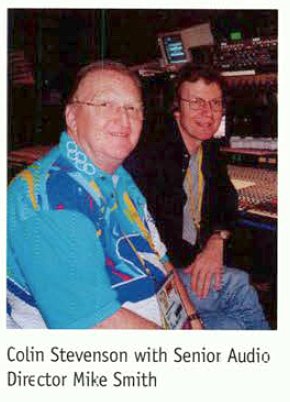

Five Ramsa consoles consoles in four control rooms were fed 192 lines via fibre optic cable, the first time a show of this scale his been cabled in digital. Several emergency analogue lines were also run, at super low impedance, as a backup.

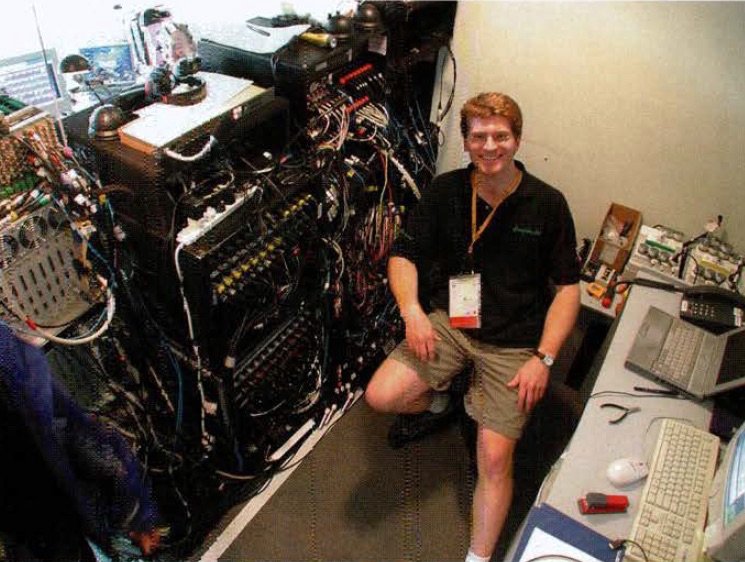

Fibre made the show possible. Klotz digital provided 13 main frames which were located around the Stadium, each being an input point for conventional analogue audio which was then converted to Klotz’s digital protocol for transmission on fibre.

A second fibre optic multicore system was supplied Otari [scan] this was the OC’s [scan] originally specified and installed system.

The four broadcast audio control rooms handled different programmes. Two were for camera effects alone each camera had a stereo microphone on front, 24 cameras went to room one, 14 to room two. Double that number for stereo inputs. The engineers in these two rooms needed to choose the vision and fade audio for each shot, with wildly different levels present at each camera mic.

Point of interest: when the camera zooms in the sound doesn’t, of course. Would you believe that a way to do this automatically is being developed, via digital signal processing (dsp), at a high tech R & D lab in Sydney?

The third control room mixed the marching bands. Control room four had two consoles in it, and mixed the whole show.

SECRETS

The production community (and we at Connections) held the show secrets, hundreds of people knew about the Cauldron which so amazed the world. Dozens of people saw Cathy Freeman light it at the rehearsal early in the morning of the Opening. The segment artistic details were all kept under wrap for more than a year.

Some things are still secret, or were until now. Connections readers were clogging our email and phone system as the ceremony wound down, asking the same thing. Why was it reported in the September issue (page 11) [PDF extract] that Richard Lush had painstakingly recorded the Sydney Symphony Orchestra, when they were there playing live and apparently mic’ed up?

Answer: the prerecorded music was used. Were the singers lip syncing? Answer: some were, some of the time! This produced some cat and mouse in a subsequent interview with Bruce and Colin, appropriately held at Machiavelli restaurant in Sydney.

Did Tina Arena sing live? “No!” they chorus, because the vocal track arrived as a final version processed for the CD release, not as the source stem. So by using it, it was obvious to anyone with decent hearing what it was.

But the audio team were coy about the rest. We know for a fact that the duet featuring John Farnham and Olivia Newton John was half live, half canned. It flipped from pre-recorded to live, at a point about half way through.

Did anyone notice? This was so the singers could ab-lib and do the ‘Good luck everybody’ part at the end.

Vanessa Amorosi sung the house down, held the last note for what seemed like a lifetime, fell to her knees, and then bounced up and said ‘thank you’ – seemingly without taking breath. Was that live or pre-recorded?

“It doesn’t matter when you have the stems,” said Colin. “That’s the beauty of having the source mix, because you can do it all so naturally.”

The answer is, the best source was used, every time. Some live, some not.

All the music, aside from the Marching band, was prerecorded and played back live in multitrack format from Fairlight’s amazing new Merlin multitrack system.

The new 24/ 48 track hard disk recorder was backed up with a Fairlight MFX3 running in tandem but not required. The Fairlight’s AES-EBU outputs were patched direct into the Klotz Digital fibre optic distribution system, where it could be collected in full glorious digital format anywhere required. Like a mile away; in the IBC!

REDUNDANCY

This was the show of disaster recovery plans. If the power went down, the system kept going, at least for a while. “We had two 7.5kva un-interruptible power supplies – big ones – on the front of house” says Bruce, “and UPS on key Klotz mainframes”.

The second front of house (FOH) console, a Midas Heritage, backed up the first. Bruce says it is a nice console.

The main console was mixed by Steve Law, with Norwest Productions CEO Chris Kennedy calling the cues. The backup console was mixed by John Simpson, supplying a backup feed to the IBC as well as live.

Tannoy monitors were used at the mixing position, which was on level 3 of the West stand, just under the dignitaries position. In case of absolute disaster, the house system at the Stadium was ready for use.

Audio feeds back from broadcast could be used live, live audio feeds could be used for broadcast. Both house (live) and broadcast had back up consoles and engineers in place, as previously noted.

And finally, there were those enormously lengthy analogue audio lines run in tandem with the fibre optic feed to the IBC, a distance of over a kilometre. “I don’t (normally) like to run analogue lines more than a couple of hundred feet” says Bruce.

SNAGS AND SOLUTIONS

RF (radio interference) was a problem in more ways than one. “We couldn’t have done it without fibre” says Colin.

“Anywhere you had a dodgy line you had 2UE (RF from this radio stations transmitter was induced into lines really strongly) come in loud and clear.”

Connections has heard of many interference issues on audio and data lines around the Stadium, mainly due to the complexity of integrating so many layers of techology for this most major event.

All problems were resolved in one way or another, a tribute to the expertise of all concerned. It pays to have time to trouble shoot.

The Governor-General of Aust:alia Sir William Dean, declared the games open, in a halting and slightly confused manner. The press leapt on this and all manner of inferences flowed. The reality was that he was aurally confused by the huge delays of 150 milliseconds or more that he was hearing!

“I asked for him to be at rehearsals” said Bruce, “but he wasn’t!”

The lectern had a hidden attribute too. Due to somewhat of a height difference between Michael Knight (Minister in charge) and His Excellency Juan Anton Samararch, the microphone cluster (2 Countryman Isomax and one Omni mic) needed to be raised and lowered a whole foot (300mm).

A meeting was held, a motorised device to raise and lower the mic was conceptualised. Colin found a linear motor for the mechanism.

One of Bruce’s crew was positioned under the stage with a switch to activate the device and a script, but before the show Bruce realised any deviation from the script might produce the amazing sight of the microphone prematurely raising or lowering before a startled dignitary and 3.1 billion TV viewers. So the crew member was relocated alongside the stage.

Glenn Helmott from the Broadcast audio team drew the short straw to become Mr Hoof. He got the horses gig. Originally it was thought the sound of five hundred hooves could be placed on the audio track – but then realised the animals would canter, trot and gallop – making it too hard to keep in sync.

Glenn used the little 10mw Sony transmitter, and ECM 50 mics which no one minded having mangled. They were mounted low on the front girth strap – but the transmitter couldn’t go down there, it was found that they tickeled the horses tummy, making it Bolshi! So the transmitters were moved up the straps, level with the saddle.

Glenn had to place these earlier in the day, and rely on the extended battery life of the unit.

There were lots of little tricks, like effects mics at the Caldron, and large diaphragm Audio Technica mics for the fireworks which were cued by timecode from the Fairlight.

MARCHING BANDS

Bruce always knew he needed to amplify some of the marching band, because although staggeringly loud, the natural horn sounds tend to go the direction that the bane (and their horn instruments) are facing.

Colin figured that about 28 of the players would be mic’ed, so Colin went to the master of frequency allocation, Bob Sloss (CEO of Syntec, importer of Sennheiser, foremost authority on UHF spectrum pertaining to

wireless microphone transmission) and obtained 44 frequencies.

16 of these were for perimeter mic’s. Bob is responsible for allocation of radio microphone and in-ear monitor frequencies at the Olympic Games. [See breakout box below.]

ASSIGNING FREQUENCIES – A MONSTEROUS TASK

Bob Sloss (CEO of Syntec, the Sennheiser importer for Australia and New Zealand) was responsible for allocation of radio microphone and in-ear monitor frequencies at the Olympic Games.

It’s a Gargantuan task, he started with a spread sheet. Broadcasters were across the top – and there are 67 of them. Channels ran down the side.

“Sennheiser gave me a plan showing you could place eight or nine reasonably intermod free channels in each TV channel” he told Connections. ”Then it was a matter of getting every request for every venue and working through them”.

Armed with an allocation from Bob, the user or broadcaster then went to the ACA (Australian Communications Authority) who are on site at the games in Sydney. ACA tested the equipment and confirmed it was transmitting en the correct frequency.

ACA had staff with scanners policing the airwaves, and found a few abnormalities here and there. “There was one spurious transmission created by three separate in-ear systems, luckily it fell into a vacant frequency” says Bob.

“People have been really cooperative. Even bands at live stages outside the venues are supplying frequencies in advance!” Once the games started, the fun kept going, in just a few days Bob found an additional 150 frequencies for people at various locations.

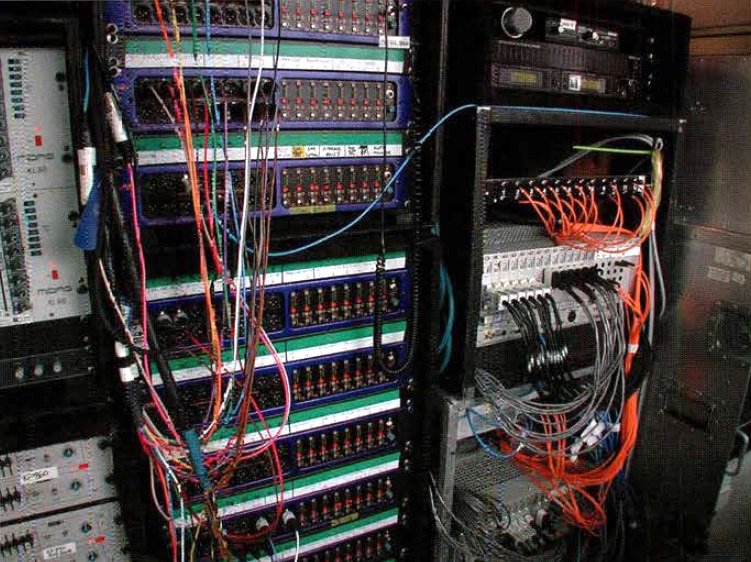

Looking at the costume design for the band, Colin figured that the transmitter would sit happily on the hat provided it was a VERY small transmitter.

Sony had a little 10 milliwatt model (most wireless systems transmit 50 milliwatts, some up to 250) which was curved and had 6 hours battery life.

A little Sony Freedom omni directional mic pointed down at the back rim of the hat.

Sony were set to work in Japan customising 44 of these to the specific frequencies that Colin had obtained. Meanwhile a communications failure resulted in the wireless mic concept for the Marching Bands being scrapped.

Colin found out some time later, and when the problem was clarified he found only five of the original 44 frequencies were still available.

Then 16 frequencies were scrounged back again, for the perimeter mic’s. These were used with Sennheiser SK5O and SK250 transmitters. SK 250s were used at the Cauldron end for ninety minutes, and were running on Lithium batteries.

“Just as well too” he says. “The main microphone source was eight Shure VP88’s, one on each of the eight conductors podiums around the ground perimeter. I was only getting the top end of the brass through them.”

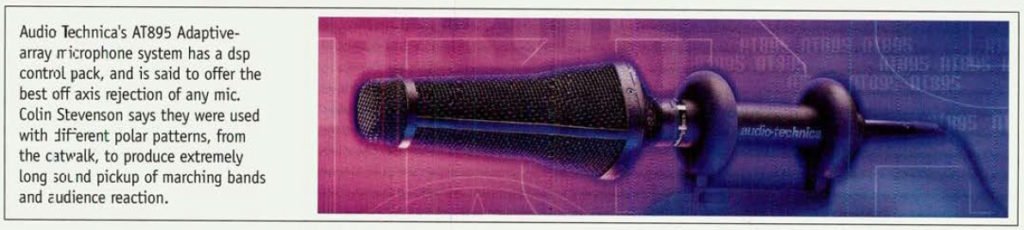

Everntualy, one of each of Tuba, Percussion, Reeds, Flutes and Mellophones (a straight French horn) were wired up. In addition there was one ‘Kookaburra’ mic, a pair of Audio Technica short shotguns on a catenary wire high above.

NBC took a feed of these for their surround 5.1 program, likely assigned to rear as surround ambience.

Audio Technica’s interesting new AT 895 Adaptive Array Microphone System was used here too. 8 were used on either side of the Stadium, hung on the catwalk truss, and evenly spaced in between KF 750 clusters.

These were programmed so the pattern was a vertical lobe, and aimed back at the audience. The idea was to get maximum audience reaction. It meant that audio earthed power points needed to be put in at every mic position on the catwalk.

A further 3 per side were pointed back in arena to get the marching bands, in a horizontal lobe pattern.

NORWEST PRODUCTIONS

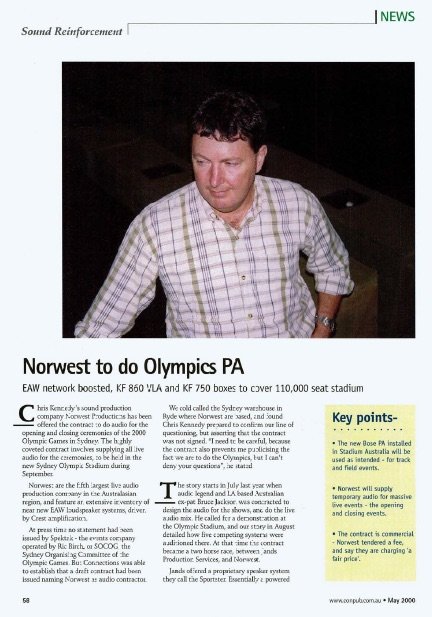

It’s been reported in these pages before now that Norwest Productions, a Sydney audio company which is owned by Chris Kennedy, won the Olympics live audio contract. [See ‘Norwest to do Olympic PA’, Connections #76, May 2000 p.58 – or read PDF extract here.]

The contract was awarded after an open audition in the winter of 1999, where a slew of systems were trialled.

Norwest demo’ed their EAW KF860/861 Virtual Line Array boxes in a cluster of two boxes. These were deemed most suitable from the ground position. A manoeuvre on the day saw EAW importer Production Audio Services supply an additional four KF 750 boxes, which were flown and pointed at the North stand, by way of demonstration of the possible option of using them.

Norwest won the job, against a fair bit of industry backlash, where accusations were levelled that EAW were buying the job, and things were said about Norwest not having the support or infrastructure to pull it all off.

Clearly both were untrue. Chris Kennedy says he was loaned some KF 750’s by Production Audio Services, the importer, and he purchased or hired whatever else he didn’t already own. And, Bruce Jackson, Mr. Fussy himself, is completely happy with the job.

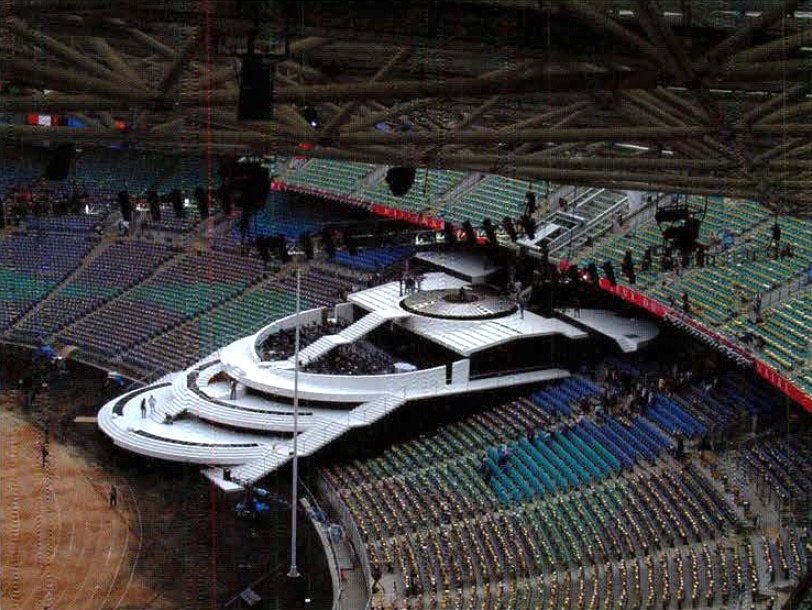

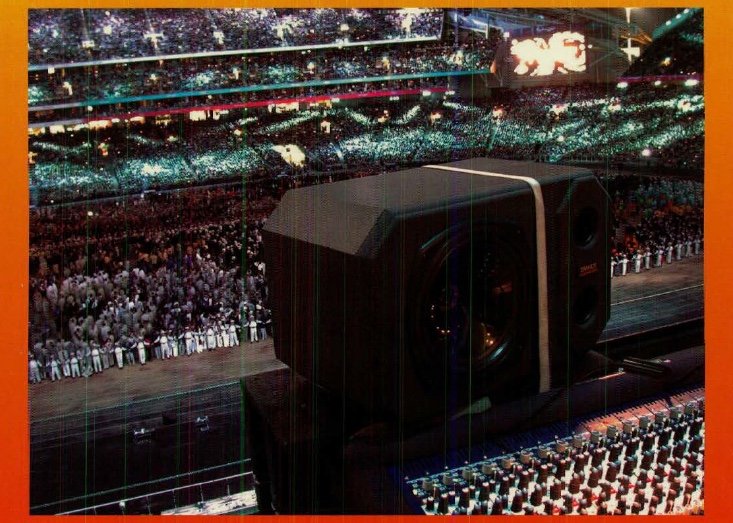

The system comprised 46 x EAW KF860/861 Virtual Line Arrays in 23 clusters of two around the floor edge of the track, facing up into the stands. They were powered by Crest 8001 and CA9 amplifiers, and processed by XTA DP226 using XTA’s Audiocore control software running faultlessly via RS485 over 1.3 kilometres of distance.

The North & South Upper Grandstand Speaker System comprised 24 x EAW KF750 in 4 clusters, each two wide and three deep-flown above the roof as stereo 1/R pairs.

They were powered by Crown VZ5002 and VZ2402 amplifiers with Pip II cards using Crown IQ. An ethernet network over fibre using three computers connected it all together.

In the East & West Upper Grandstands, the system was made up of 32 x EAW KF750 flown as sixteen clusters of two on their sides using custom Norwest designed rigging. There were eight symmetrical clusters on each side.

Once again they were powered by Crown VZ5002 and VZ2402 amplifiers, with Pip II cards using Crown IQ. (On ethernet over fibre again.) The House delay line was used, it consisted of five Bose 9702’s per side plus there was a third (Norwest supplied) line of delay comprising seven Zeck T-3 cabinets per side.

The latter were powered by Crown VZ2402’s with Pip II cards using Crown IQ.

Monitors were made up of 20 x EAW SM200ih wedges and 8 x Zeck T-3’s. There were around 20 IEM’s – (In Ear Monitors); mainly Shure PSM600 & PSM700 plus a few Sennheisers (slim packs for girls in slinky dresses).

There was an FM system (on two especially licensed FM frequencies) for bulk in ear monitoring for horse riders, tap dancers and various cast members and stage managers.

There were a total of just under 1,000 of these units!

The FOH control comprised 2 x Midas Heritage 3OOO / 48 channel consoles, with a Midas XL-3 for monitors, and 2 Mackie CFX20 sidecars. EQ went through about 20 Klark Teknic DN360’s. Compressors included 2 x DBX160SL (main system compressors), 6 x DBX566 Tube Compressors (inserted on FOH), 6 x DBX1046 quad compressors (Insert FOH & Mons), 6 x Drawmer DS201 did gating, and there were Lexicon 480L, TC M5000 Eventide H3000, and Yamaha SPX990 effects.

The Active splits between consoles and broadcast were done with 9 x XTA DS800’s.

Microphone world included a comprehensive array of Audio Technica microphones (including 4050’s, 4051’s, 4047’s, 4041’s and 3525’s for the orchestra mic up. All radio microphone were Shure U1 series with Beta 87 capsules. Tie headsets were DPA’s, into Shure U1 beltpacks.

ZERO HOUR

Connections sat in on a live rehearsal of the Opening two days prior. It ran very smoothly, and despite being in the worst seats in the house all vocals and announcements were both intelligible and loud enough.

Helicopters circling created ambient noise, and a slight to moderate wind blew the frequencies about.

Bruce squawked big time about the helicopters. John Simpson generated a list of sensitive moments and sent it to the assistant director, who kept the helicopters out during these parts.

The live sound component of the show was the greatest challenge, I say that with respect to broadcast, lighting, staging and the actual talent on hand. Getting so many sources, spread around four acres, delivered to each of 110,000 seats at appropriate gain and with intelligibility is a task few could achieve.

Bruce Jackson pays tribute to Norwest Productions. “I’m very fussy”, he says. “I don’t often work with audio companies other than Clair Brothers. Chris Kennedy has a really good team. I wouldn’t have any trouble hiring many of them internationally”.

Bruce’s background should be known by most readers, he is probably the greatest live sound designer in the world today, although he would shrink from the description.

Australian born, he was long serving designer and engineer for Elvis, Springsteen and currently Streisand and is based in LA. He is the ‘J’ in Jands, which stands for Jackson and Storey.

The live telecast of the opening appeared seamless in audio terms. We were impressed at the smooth levels, response and reach of the system.

Colin Stevenson has worked in Television Audio since 1958, and with Event TV Producer Peter Faiman since 1964. He now runs Production Audio Services with son Graeme and wife Margaret in Melbourne. Amongst other lines they distribute EAW in Australia.

Colin and Bruce are unified on the need for the right people, to communicate effectively and work together to produce a result. While the layers of bureaucracy attached to the Olympics could be bewildering, “you just had to find a worm hole and get through” says Colin.

They both stressed, at different times, that we emphasise the co-operation between their departments, which obviously contributed to the enormous success of this show.

Honourable mention dept:

There’s no way Connections can credit all the crew or all the departments who worked on the Opening Ceremony. The program credits extend six pages! We do note the following, and apologise to anyone miffed at missing out:

Communications Contractor: PA People

Fireworks: Foti International

Staging: Edwin Shirley Staging Australia

Technical Director: Morris Lyda

Assistant to TD: Joanna Lloyd

Operations Director: Malcolm White

Technical Manager: Michael Auckland

Art Dept Supervisor: Brian Edmonds

Senior stage manager: Anneke Harrison

Live Audio Crew

The live audio crew comprised just under 40 staff plus 16 volunteers. Principal personnel were:

Bruce Jackson – Audio director

Chris Kennedy – CEO of Norwest,

John Simpson – Assistant audio director

Steve Law – Project manager and FOH audio engineer

Ian Baldwin – Assistant project manager and senior system

engineer

Ian Shapcott – Monitor engineer

Tony Szabo – Control room system engineer

Randy Fransz – Speaker system engineer

Peter Wood – Audio stage manager

Peter Twartz – Radio microphone & IEM system engineer

Steve Logan – Fairlight engineer

Keith Prestidge – Klotz System Engineer

Broadcast Audio Crew

Colin Stevenson – Broadcast Audio Producer

Mike Smith – Senior Audio Director

Tim Davies – Audio Director (BBC on loan)

Milan Milenkovic – Audio Director FX

Steve Korres – Audio Director FX

Steve Delmenico – Audio Director Systems

Glenn Helmott – Audio Director Systems

Neil Laycock – Audio Tech Support

Matt Louie – Audio Tech Support

Mary Graham – Senior Audio Assistant

Al Craig – Head of Audio, SOBO.

• Plus another 17 assistants and volunteers.

Other aspects of the production covered in this edition were:

- Blasting the Broadcast by John Grimshaw (p.26) – PDF extract

- Flying effects by Madeleine Murray (p.28) – PDF extract

- Lighting up the Fish by Madeleine Murray (p.30) – Page 3 of PDF extract

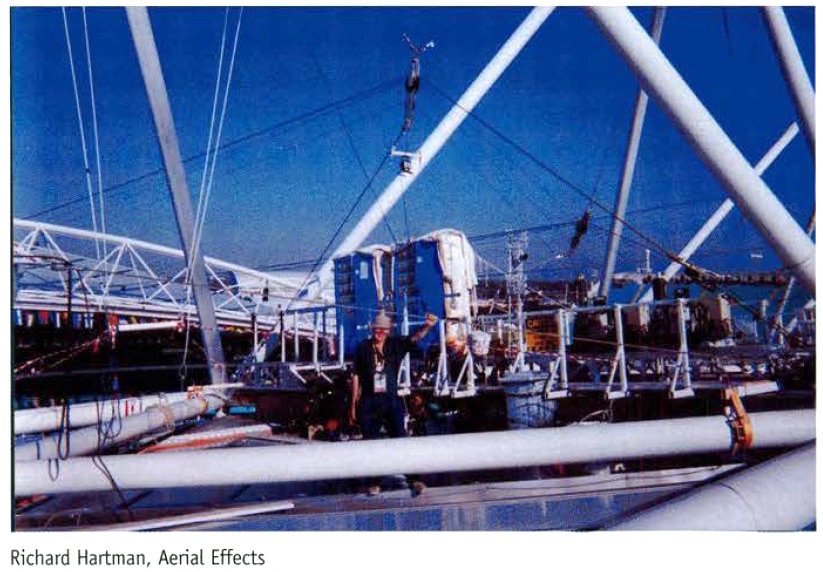

- Riggers on the Job by Julius Grafton (p.32) – Page 5 of PDF extract

Or read the whole issue here for free:

Connections Magazine – October 2000

LIGHTING | AUDIO | VIDEO | STAGING | INTEGRATION

Entertainment technology news and issues for Australia and New Zealand

– in print and free online www.cxnetwork.com.au

© VCS Creative Publishing

Subscribe

Published monthly since 1991, our famous AV industry magazine is free for download or pay for print. Subscribers also receive CX News, our free weekly email with the latest industry news and jobs.