THE GAFFA TAPES

23 Jun 2025

THE ANALOGUE / DIGITAL PARADOX

Subscribe to CX E-News

Snippets from the archives of a bygone era

The emergence of solid-state audio consoles in the late 1960s is often overlooked in the fog of the ongoing conjectural analogue/digital wars, despite the fact that these analogue consoles replaced vacuum tube-based consoles. Sound engineers at EMI, particularly Geoff Emerick, who used the solid-state EMI TG12345 on The Beatles’ Abbey Road album, expressed concern about the loss of warmth and harmonic distortion when compared to the previous tube-driven REDD consoles. Unlike present-day arguments about the warmth of analogue as opposed to the alleged harshness of digital, this was a solid-state versus vacuum tube contention in a totally analogue domain.

Not only do discussions about the pros and cons of analogue and digital equipment become confused with differences between solid-state and vacuum tube equipment, but analogue storage gets thrown into the mix with the analogue signal, and they are two different entities. And when analogue signals and digital files coalesce, does the whole argument become paradoxical?

Those of us who worked in pro audio in the 70s, 80s, and 90s were more than comfortable with analogue mixers and outboard equipment. This was the solid-state era, and few of us were locked into archaic equipment for nostalgia’s sake, especially when new and exciting developments were emerging. We sought out mixers with better-sounding microphone preamplifiers and EQ, and especially those that had more headroom so we weren’t red-lighting at the input stage whenever there was a solid attack signal.

I heard my first 45 rpm vinyl recording of The Beatles in 1963, and I was elated. My uncle played From Me To You, and the flip side, Thank You Girl, on my grandmother’s valve radiogram. Today, ‘back to the future’ enthusiasts can walk into a consumer electronics store and buy solid-state record turntables and new vinyl pressings of The Beatles’ albums. But it’s a different listening experience from the sound waves that radiated from my grandmother’s vacuum tube radiogram with its heated valves and ageing components that also generated a musty, smoky odour that permeated through the grill cloth. However, a different experience doesn’t suggest any superiority, and I am as faithful to vinyl recordings as I am to the ice chest that my grandmother had prior to the mainstream use of refrigerators or the washboard and hand-cranked wringer she used for washing clothes.

The vinyl record renaissance is approaching its 20th year, and although their solid band of aficionados swear that vinyl is superior to digital media, it seems these fans are more motivated by the touchy-feely and nostalgic experience than any evidence of technical superiority. Cassette tapes are also on the comeback trail, with spurious claims being made about their supremacy. These, in their day, were never purchased because of their high-calibre audio quality, nor were they a cut above vinyl; more so, it was their portability, their ability to be played in car cassette radios and in Sony Walkmans, and also their ability to copy and share material. But the little cassettes were problematic, often playing out of sync and very often jamming, and the universal remedy for this not-so-revered media was a lot of banging and turning the cogs with a pencil to free them up.

I once owned a Tascam 234 Syncaset 4-track rack-mount cassette recorder, which I connected to an audio patch bay. There was a lot of patching and bouncing down tracks, which created audio losses, and cassette tape wasn’t the best format to start with. It defies logic to think that I would swap my multitrack DAW (digital audio workstation) for a 4-track cassette dinosaur, especially when Tascam has moved into the digital age with its digital consoles and recorder players.

Vinyl records still have an RIAA equalisation curve that was introduced in the 1950s to improve sound quality, reduce groove damage, and make room for the required space on the record. In the cutting process, the bass frequencies have to be reduced by 20dB and the high frequencies boosted by 20dB. The phono signal is extremely low level, and in addition to equalising the bass and high frequencies back to their original level, the signal has to be boosted by the phono preamplifier some 40-60dB to line level so it can be processed by the amplifier.

Even from the 1960s onwards, these phono preamplifiers were solid-state, and most mainstream domestic turntables suffered from limitations and introduced noise, hiss, and phase errors. There was also ‘wow’ and ‘flutter’ on vinyl records, which referred to speed variations during playback, causing pitch fluctuations. ‘Wow’ described slow, gradual pitch variations, while ‘flutter’ represented more rapid changes. Then there were variations in the turntable mechanics, and not everyone had the budget for an SME tone arm or a turntable with an expensive external phono preamplifier.

Apart from the dust and scratches, vinyl’s failings went largely unnoticed by mainstream users and listeners, and these shortcomings differed according to the type of turntable the record was played on. My first guitar teacher advised me to tune my guitar to any vinyl record that I played along with, or I would be out of tune because playback variances altered the pitch of the original recording, and he was right. Similarly, cassette tapes invariably played out of sync.

CDs were the digital successor to tape and vinyl, but they were also problematic and subject to scratches and smudges, and they often skipped or repeated tracks, and because of these annoyances and interruptions, they were subsequently banned as playback media at some performance concerts like eisteddfods, so the performers had to fall back on cassette tapes. In the late 90s and into the 2000s, I used a digital Sony MDS-E58 MiniDisc recorder/player for these events and for my own shows, and I still hold the minidisc in high esteem. Unfortunately, the emergence of the MP3 brought about its demise. A more serious renaissance of physical media for me would be the minidisc, not vinyl or cassette tape.

All vocal audio originates as analogue, and digital audio has to be converted back to analogue before we can hear it through speakers or headphones. Analogue audio can be a natural representation of the original waveform, but its basic storage mediums of tape and vinyl, especially for the domestic market, have been problematic and bulky with the need to be driven mechanically. Even in tape’s purest form in the recording studio, it was an expensive commodity. Digital files solved this problem.

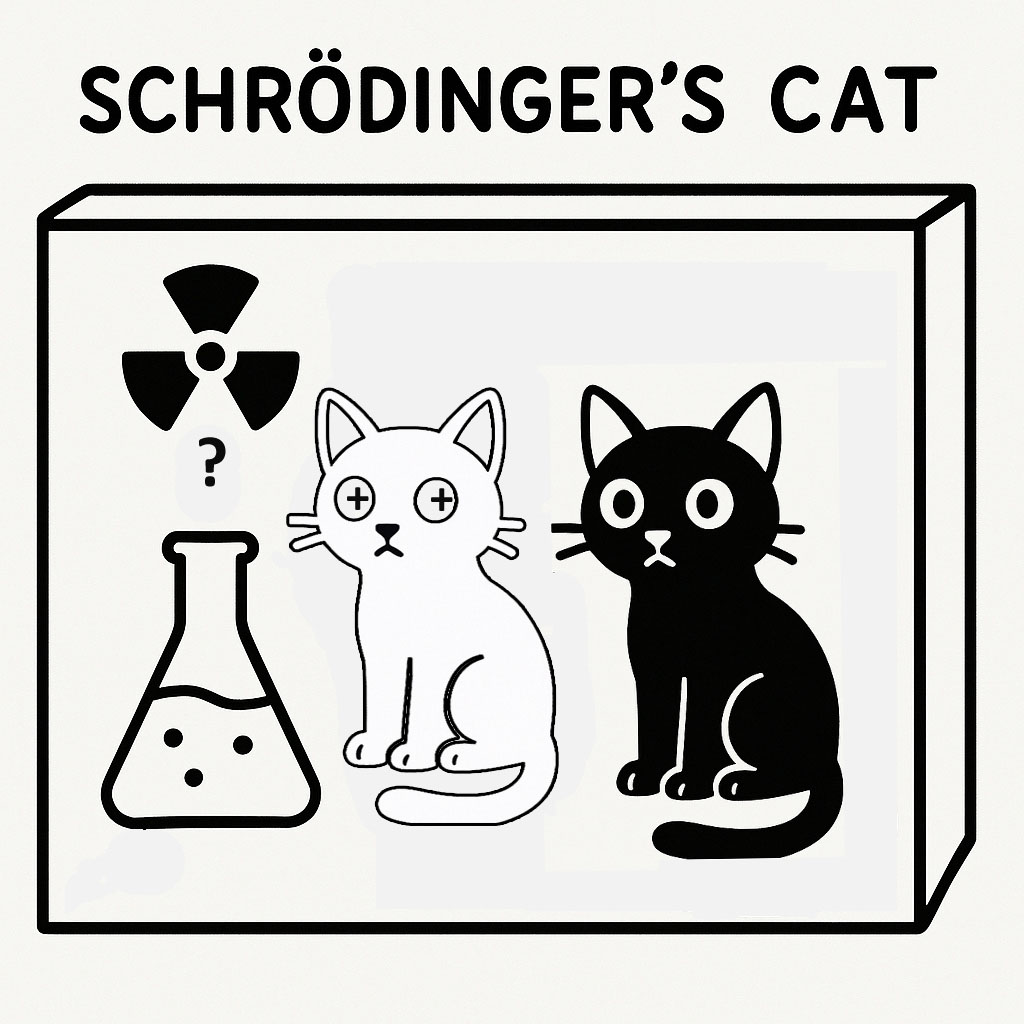

So, is there a legitimate analogue versus digital argument that can be rationally debated, or is the argument analogous to the quantum physics argument of a superposition, which is the phenomenon where an object has the potential to occupy different states, which can change when observed or measured?

The Beatles’ early recordings at EMI’s Abbey Road studio in 1963 were engineered by Norman Smith via a tube-driven REDD console and an EMI BTR 3 twin-track tape recorder; the instruments were recorded on one track and the vocals on the other, and the two tracks were mixed down to mono. In making digital masters of The Beatles’ records, both George and Giles Martin took great care to preserve the analogue sound of those recordings while they were using digital devices, including Pro Tools workstations operating at 24-bit 192kHz resolution and Prism A-D converters. Striving to preserve the integrity of an analogue recording using digital tools does suggest that it sits in a superposition when stored on a digital file.

Perhaps suggesting an analogue/digital superposition is a better argument than Schrödinger’s Cat, the thought experiment suggested by Erwin Schrödinger in 1935 to disprove that subatomic particles can exist simultaneously in multiple states. The virtual experiment conceptualised a cat in a box with a radioactive substance and the probability of the radioactive substance becoming active and killing the cat. Schrödinger proposed that, according to quantum physics, until observed, it could not be known if the radioactive substance was active or not, and therefore he satirically proposed the paradox that, until observed, the cat could also be in both states, alive and dead.

The digital process is the manipulation and storage of both digital and original analogue sources, and it seems that is akin to Abbey Road’s philosophy because when they moved into their Angel Studios in Islington in 2021, they installed a Solid State Logic ORIGIN 32-channel analogue mixing console with an SSL UF8 Advanced DAW Controller. Abbey Road also sidechains a Chandler Limited RS124 analogue compressor to the SSL console for use when required, and Abbey Road still utilises an array of analogue microphones, including the Neumann U87Ai, Neumann U47, AKG C414, and even Coles 4038 and Royer 121 ribbon microphones. So, if a totally analogue recording is digitised and sits on digital media, doesn’t it exist in both states until it is played and audibly observed as analogue with both its digital and analogue components?

Main Image: Abbey Road Solid State Logic ORIGIN 32-channel analogue console

Subscribe

Published monthly since 1991, our famous AV industry magazine is free for download or pay for print. Subscribers also receive CX News, our free weekly email with the latest industry news and jobs.