News

30 Jun 2022

The Gaffa Tapes: So You Want To Be In Pictures?

Subscribe to CX E-News

Snippets from the archives of a bygone era

The myths and mysteries of recording sound for film and video lured me to travel what I thought would be the long and winding road to success. Instead, it turned out to be a troubled journey along a rocky road of misadventure.

In the mid 90s I enrolled in a crash course in film production at Sydney University. We shot on film, recorded on Nagra analogue tape recorders, and mixed on Steenbeck flatbed editors.

During the course I learnt that audio was largely an enigma in the industry. When I asked the lecturer what special skill-set was required for film sound, he replied, “Well, you have to listen out for things on the set.” The adroitness to record one or two microphones while listening for approaching aircraft or the distant buzz of a chainsaw now seemed less intimidating than my previous vocation of wrestling with a live 24 channel band mix.

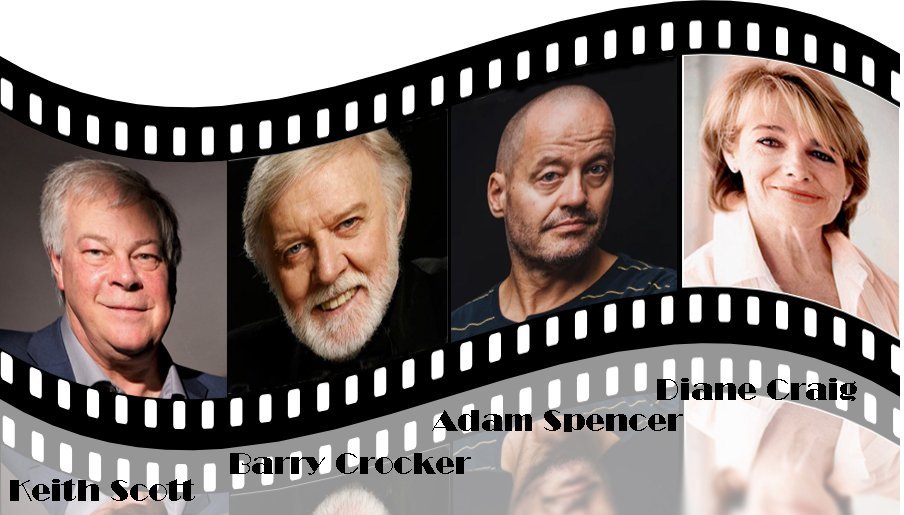

It was the film school that gave me my first paid gig as a sound recordist. This was a promotional video shot on the grounds of Sydney University featuring Australian comedian, media personality and radio presenter Adam Spencer. Being a rookie, I gaffed the lavalier mic directly onto Adam’s bare chest, but later found that removing the gaffa tape from his hirsute chest also removed several of his chest hairs. However, Adam was extremely pleasant about the ordeal.

In 1998 I joined a professional video crew in Sydney’s eastern suburbs. I was the audio guy for a host of corporate videos, swanky parties, fashion parades, bar mitzvahs, and various functions including the recording of the performances at the reopening of the Central Synagogue, Sydney.

I used a Rode NT2 to record a choir that had been flown in from Israel for the Synagogue gig. I also used a SONY ECM-969 stereo condenser mic to record three Jewish tenors who were emulating the performance style of The Three Tenors (Plácido Domingo, José Carreras, and Luciano Pavarotti).

Not having the luxury of a multitrack recorder, the audio had to be mixed and sent at line level to one of the Sony Betacams doing the two-camera shoot. At the sound check I had a nice mix of the choir and the three tenors, but when the director asked to hear the mix in the headphones it was his opinion and the opinion of my own crew that I had the choir too loud in the mix. An argument ensued where I pointed out that this was a dump into the camera and there could be no remixing. Nevertheless, I was instructed to attenuate the choir in the mix. Some days later I got a call from my boss, who said, “They’re complaining that the choir is too low in the mix.”

Things were to take an even worse turn when my company asked me to manage the technical side of a big birthday bash for Sydney celebrity restaurateur Wolfie Pizem, whose restaurants included the Russian Coachman, Wolfie’s, The Waterfront, and Italian Village.

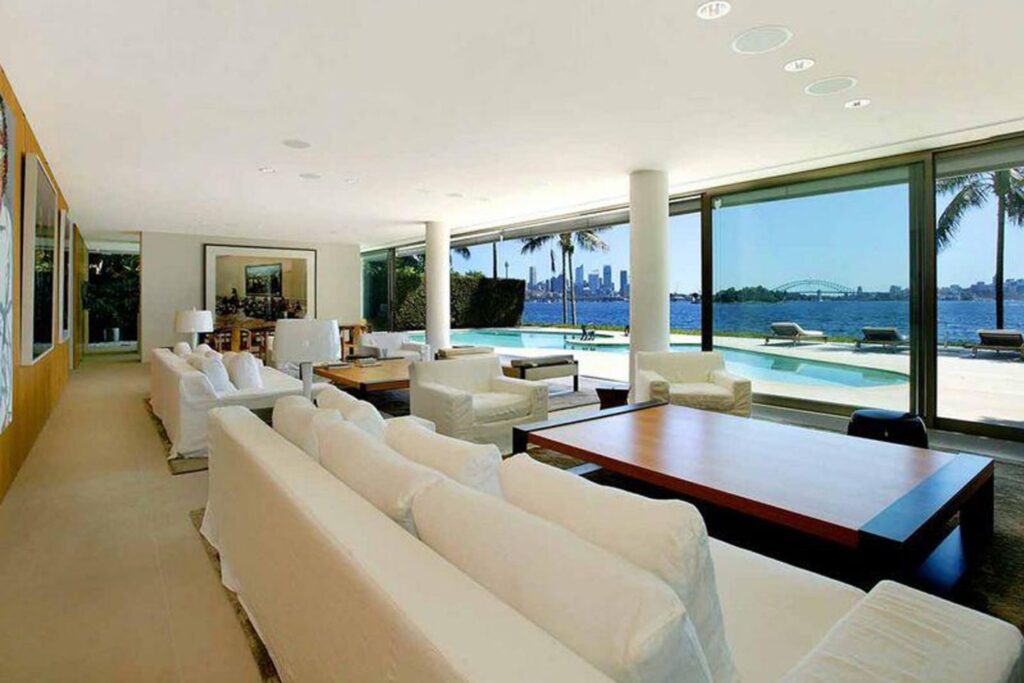

I was accompanied by one of the principals of my company to meet Barry Crocker and Keith Scott at Wolfie Piezem’s Point Piper mansion. Wolfie’s wife Karen played host as we dined on the patio of the plush harbourside residence, an estate which has since changed hands a couple of times, eventually fetching a cool $38 million in 2014.

Barry Crocker was the producer and MC of the event and Keith Scott was booked as the headline act. The meeting was a surreal event for me as I was a huge fan of both entertainers. I had seen both Barry McKenzie movies starring Barry Crocker and I had also seen Keith Scott live performing his brilliant impressions. In fact, Keith Scott voiced the Looney Tunes characters for commercials in Australia and for Warner Bros. Movie World.

Piezem’s birthday bash was to be the usual two-camera shoot with the audio sent to one of the Betacams from the mixing console. This was how we did functions such as fashion parades where the playback music and live microphones were mixed then sent via a snake to a Betacam. The snake is simply two balanced microphone leads and an unbalanced return for monitoring the camera audio, which is of the utmost importance. On simple location shoots I used a Shure FP32 field mixer, which could switch between monitoring the mixer audio and the camera audio. When using a multichannel mixer, the camera return is simply patched into a separate channel and monitored via PFL.

Expectations are usually high when meeting celebrities and Barry Crocker and Keith Scott didn’t disappoint. Barry had some great production ideas for the event and he and Keith worked seamlessly to fine tune them. It was simply my task to advise what could and couldn’t be done technically, or how the production could be enhanced. However, my associate was noticeably uneasy with all the tech talk and perhaps wanted to focus more on the decorative aspects. And, on the walk back to the car I was told, “We’re not doing all that.” I was gobsmacked! However, I still had to put the gig together.

I met with a technician from Lots of Watts at the event location, which was the 760 sq metre Overseas Passenger Terminal at Sydney Harbour. Here we worked out the audio and lighting requirements. The quote was reasonable and the arrangement was exciting, so it was approved. But in an abrupt flip-flop the principal, who didn’t want to go with the agreed pre-production, cancelled the sound and lighting.

Once again I had struck another rut along the potholed road of my career, and subsequently I tendered my resignation. There was no joy in the call I received from the distraught principal asking for help on the event night when things began to go pear-shaped. I agreed to attend and help but the call was terminated, and I was never briefed on the outcome.

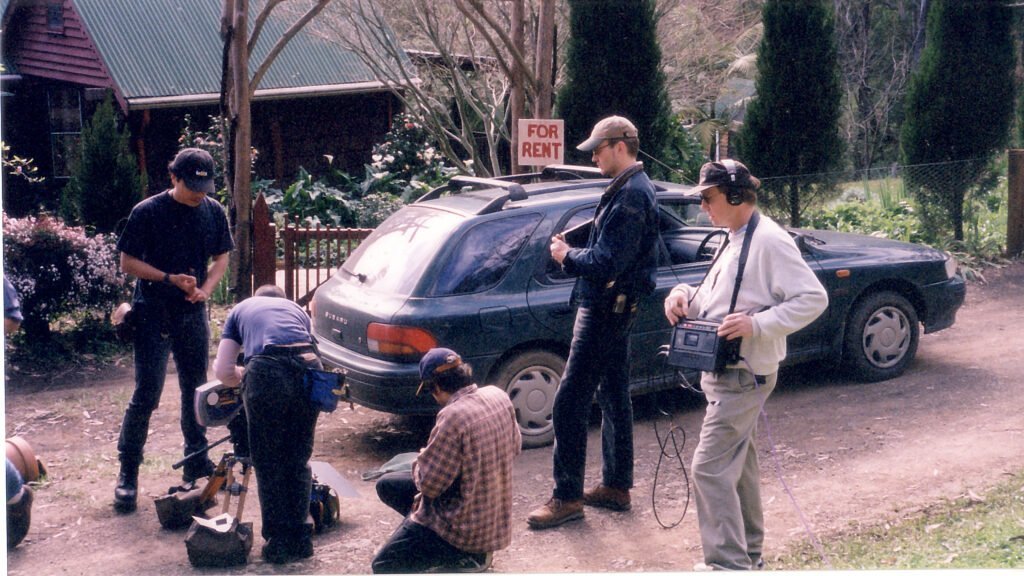

My first job recording sound for film entailed a six day shoot on location at Berry, NSW for a short film entitled Portrait in Time starring Diane Craig, an accomplished actress and wife of Garry McDonald (Norman Gunston). The film employed some very talented professionals. However, I neglected to tell the crew that this was my first location film shoot.

Day one on the set, the First AD (First Assistant Director) commenced: “Everybody quiet on the set,” etcetera, then “Turnover!” Then everything stalled in silence. So he started again, and when he got to ‘turnover’ I noticed that everyone was firmly focused on me.

“Is there a problem with the sound, Brian?” he said.

I was only familiar with the terms ‘roll sound’ or ‘audio’. “Sorry, just checking level.” The First AD didn’t buy it, and that evening at drinks he let me know of his displeasure. Nevertheless, that was my only faux pas, and we went on to have a good working relationship.

The audio recordist’s reply to the First AD is always, ‘Speed’. The old analogue Nagra tape recorders took a few seconds to get ‘up to speed’, the same speed as the film camera. I recorded film sound onto a Sony TCD-D10 PRO 2 DAT recorder, and DAT still had to get up to speed.

Working with the crew on Portrait in Time was an incredible experience and should have been a stepping-stone for most of the crew to further their careers in the industry. However, filmmaking in Australia was as tethered then as it is now, so after doing sound on a few more short films I got a haircut and a real job (apologies to George Thorogood).

(PS, I didn’t really get a haircut.)

Subscribe

Published monthly since 1991, our famous AV industry magazine is free for download or pay for print. Subscribers also receive CX News, our free weekly email with the latest industry news and jobs.