Subscribe to CX E-News

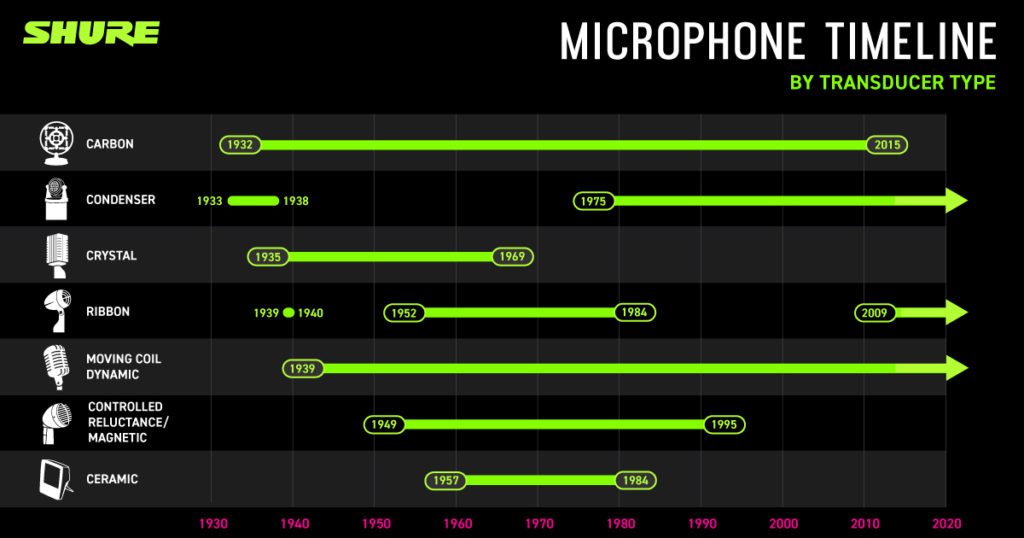

The genesis of crystal microphones began with the investigation of the piezoelectric effect by Jacques and Paul Curie in 1880. During the early 20th century, piezoelectric transducers were being created. By 1930, the Brush Development Company had improved the technology and held many patents for the Rochelle salt crystal, central to the manufacture of piezoelectric transducers. In 1933, the Astatic Corporation began marketing a crystal microphone for public address, home recording, and two-way radio applications.

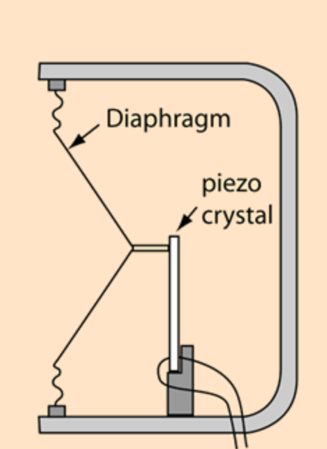

The Operating Principle

All microphone cartridges – regardless of type – are transducers that convert sound waves into electrical energy. To understand how crystal microphones work, here is an excerpt from “Microphones Explained for Beginners”, an article that appeared in the August 1938 issue of Radio-Craft:

“The principle of operation depends upon the piezoelectric effect, i.e., voltage produced in certain crystals when subjected to mechanical stress, bending, stretching, etc. [Editor’s note: The original article also described the low-output sound-cell type.]

“The diaphragm type will give much greater output, eliminating in most cases the need for a preamplifier, but it has the disadvantage of limited frequency response. This type of crystal microphone is most used for voice work.”

Shure and Crystal Mics

In 1935, Shure offered the company’s first crystal microphones – the Model 70, the Model 71, and variations of these units. The price range was $22.50 – $70, or $423 – $1,315 in today’s currency.

Shure and other mic manufacturers of the era licensed the technology first developed by the Brush Development Company. The 1935 Shure catalog stated, “Shure Crystal Microphones are the result of exhaustive engineering development by the technical staff of ‘Microphone Headquarters,’ working in cooperation with scientists at The Brush Development Company, the inventors of the Bimorph piezoelectric crystal unit.”

Every Shure crystal microphone carried a label, often inside the product, stating that it was manufactured under a license agreement with the Cleveland, Ohio-based company.

Crystal microphones were popular in many of the same applications as the carbon mics that Shure first offered in 1933 – public address, broadcast, telephony – but also home recording applications.

Unlike carbon mics, crystal microphones didn’t require an external power source (eliminating the hiss associated with the constant DC voltage running through the carbon granules) and offered a wider frequency response. But they weren’t as rugged. The piezoelectric Rochelle salt crystals were prey to heat, moisture and humidity.

During the 1950s, a “ferroelectric ceramic” material, barium titanate, began to replace Rochelle salt in transducers such as microphones and phonograph cartridges. Unlike Rochelle salt, barium titanate did not lose its piezoelectric characteristics when exposed to high heat or humidity.

The first Shure ceramic microphone appeared in the 1957 catalog as the Model 215. Dynamic and electret-type condenser cartridges supplanted crystal and ceramic microphones in the 1960s.

By 1969, the Shure catalog listed just three crystal mics: the Model 715 ($9), the Model 710 ($13), and the Model 777 ($27); $63, $91 and $189 in equivalent costs today. In 1970, Shure discontinued the three remaining models.

Crystal Microphones in the Shure Archives

Since Shure manufactured carbon microphones for over 35 years, there are dozens of artifacts – microphones and microphone parts – in the Shure Archive. Here are a few favorites:

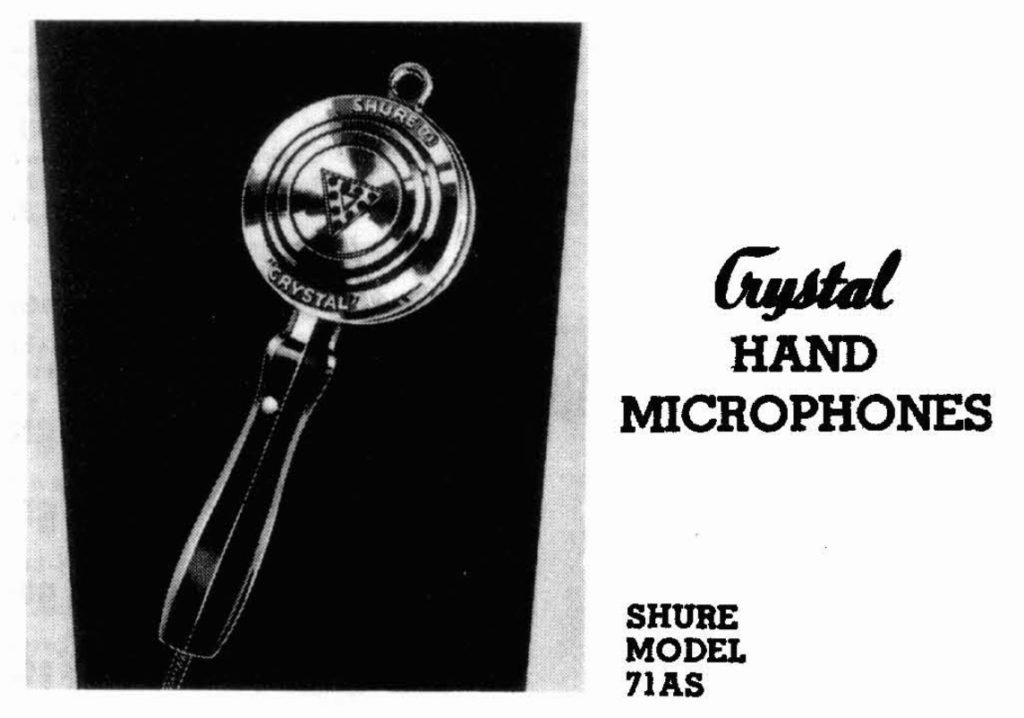

71 Series Handheld Microphones

Making their debut in 1935, the Shure Models 71AS, 71A and 71H were promoted as “Close- Talking” crystal hand microphones, designed to minimize crowd noise in Public Address applications. Models 71AS (with a push-to-talk switch) and 71A (no switch), featured a screw-on “rubber-black-japan” (lacquered) handle, making these models among the first commercially-available handheld microphones.

The 71BS, a non-“Close- Talking” model was added in 1937, but none of the Model 71 microphones appear in the 1938 catalog. However, the sleek appearance of the series lives on today in the Beta 181.

700A, 701A, 702A

The cover of the 1937 Shure Microphones and Accessories catalog reflects the popularity of the Streamline Art Deco design trend in the mass production of everyday products.

These crystal microphones boasted the identical Shure-engineered “outstanding features” – “Ultra” wide-range reproduction, screen-protected cartridge, “Moisture- Sealed” high capacity Grafoil crystal, high output, curvilinear diaphragm – in Spherical, Swivel and “Grille-Type “designs.

Used in military applications, a Model 700A could have changed the course of history when, on December 7, 1941, a radar operator radioed commanders at Fort Shafer in Honolulu, Hawaii of the presence of Japanese planes 132 miles north of Oahu. The lieutenant taking the message instructed area radar operators to “forget it”.

Model 708A

In 1940, the Model 708A “Stratoliner” joined a family of the Shure microphones with fanciful names that eventually included the Spher-o- Dyne, Rocket, and Monoplex.

The airship (or zeppelin, blimp, dirigible) – inspired design of the Model 708A crystal microphone was shared with the ribbon Model 508 that also debuted that year.

In addition to its sonic qualities, the Shure 1940 catalog touted the 708A’s good looks, stating that it also improved “the appearance of sound set-ups.” Production of these mics was suspended from 1942-1946 to conserve materials for World War II. The 708A was revived after the end of the war.

Remains of the Day

In 1999, Hohner, the German manufacturer of harmonicas, melodicas and accordions, bought the molds (and the last existing piezoelectric salt crystals) from Astatic to continue production of the popular JT-30 Blues Blaster crystal microphone.

Favored by blues harmonica players for its dirty, distorted Chicago blues sound, the rechristened Hohner 1490 Blues Blaster ended its production in 2013.

Shure bulletshaped mics first appeared in 1939. These Bullet mics, appreciated by harmonica players because the case can be comfortably cupped into one’s hands, were available with different elements: crystal, ribbon, controlled magnetic, and moving coil.

In 2020, the Shure 520DX Green Bullet, a moving coil design, endures as a popular blues harp mic.

CX Magazine – June 2020

LIGHTING | AUDIO | VIDEO | STAGING | INTEGRATION

Entertainment technology news and issues for Australia and New Zealand

– in print and free online www.cxnetwork.com.au

© VCS Creative Publishing

Subscribe

Published monthly since 1991, our famous AV industry magazine is free for download or pay for print. Subscribers also receive CX News, our free weekly email with the latest industry news and jobs.