History

18 Dec 2020

This Could Be Serious

Subscribe to CX E-News

The following is an excerpt from the book ‘This Could Be Serious’, by founder and ex-publisher of CX, Julius Grafton. All proceeds from sales of the book go to charity CrewCare.

“Julius Grafton writes like he talks – direct, no bullshit, in-your-face, full of energy and with a healthy disdain for pretence. He tells good stories, full of insight and hard-won wisdom. There’s a lot of all of this in his book.” – Stuart Coupe

“Order has finally come from the chaos of Julius Grafton. All those nagging questions I have had about the author are now answered and in such a riveting way. I could not put this book down. Julius discovers the meaning of life and unlike most of us, has actually written it down.” – Stephen Devine

“I really hated Julius back in the 1990s when he ran Connections magazine. I would write letters to the editor calling him on grammar, sexism, and general lack of political correctness. Since then I’ve read some of his material from time to time, and feel that he has the right grasp on life. So I did buy this book on Kindle, and now I want to meet him. Do yourself a favour.” – Sheila Yates

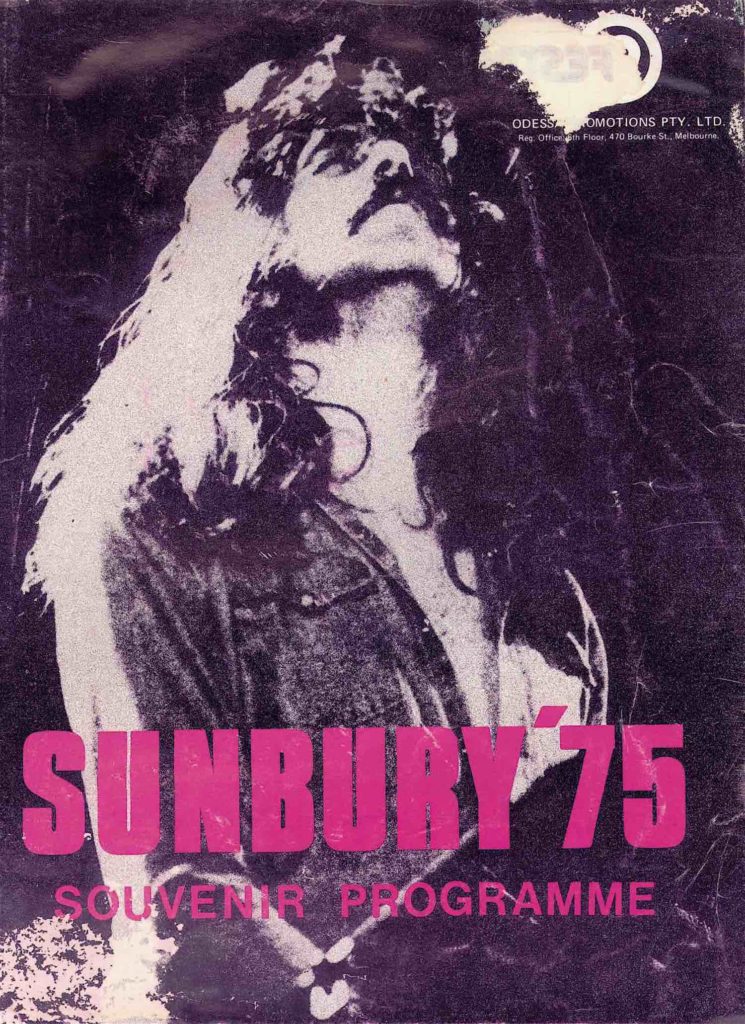

I Was A Roadie

The “Flxible” Clipper coach roared up to Campbelltown Civic Centre, the bus leaving a trail of black smoke. Built in the late 1950s, these American long-distance coaches were used by Ansett around Australia, and AC/DC had purchased a well-travelled version for use as a tour bus.

The band’s gear was in the back, and a roller door was installed at the side in front of the rear engine compartment. It was 1975.

The Flxible part of the Clipper name wasn’t a typo, there was a trademark issue that resulted in the strange name. The coach was a thing of awe with a swept rear end below a big air intake scoop. The AC/DC bus carried the band, backline, and a smallish PA system.

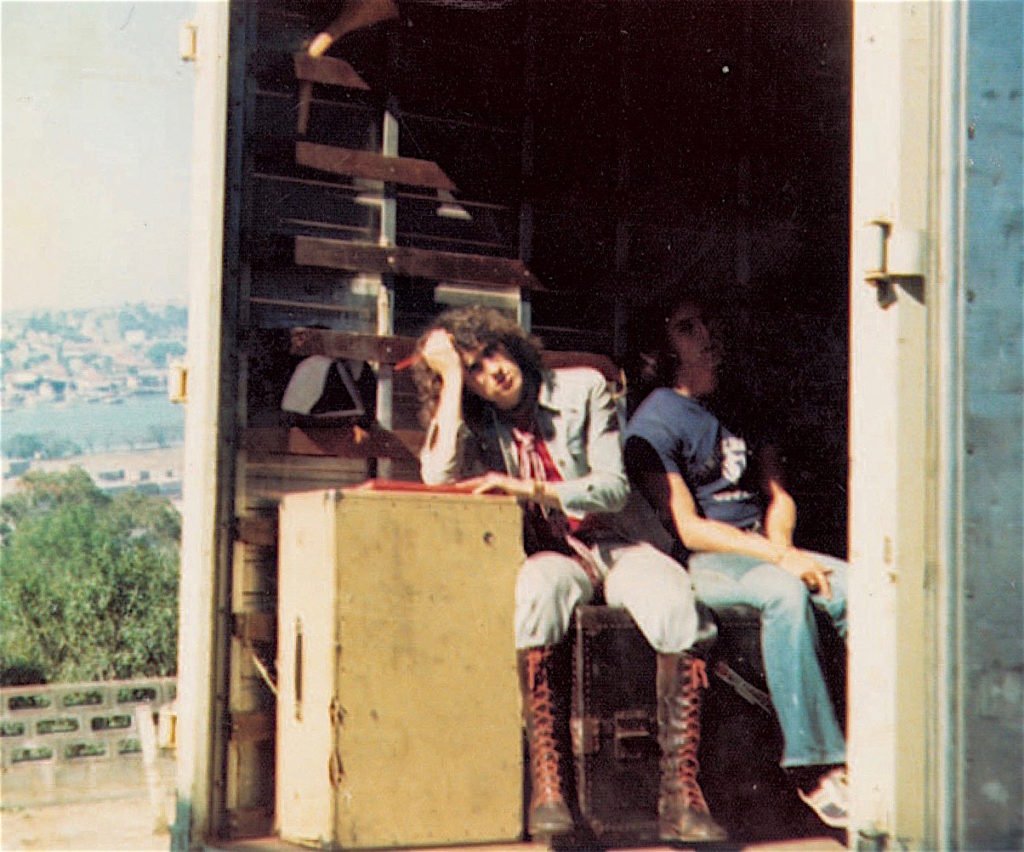

The crew was accustomed to working fast, since the band was on board – there was never any waiting around for the group to roll up. Bon Scott would leer out the windows at girls, waving a bottle of Red Label, and with a fag hanging out of his mouth.

The coach was handy at the end of a gig for the band to retire into while the crew loaded it.

Back then, no one thought about consequences, and I think there were few. The parade of gorgeous young—and some were too young – women were essentially competing to get laid. We assisted them in their endeavours.

Sex, dope, and rock n’ roll all equalled teenage heaven. That’s what was on the cover of the Daddy Cool album, and those were primary drivers in our lives. The free love, drop-out movement from California hit Australia in 1971, and we were all of that era. People would get naked, and get stoned, without much prompting at all.

Our lives were flipped upside down.

The rest of the world was mostly straight and conservative, TV was slowly transitioning from black and white to colour, and it wasn’t that long ago that square people wore hair cream and danced under fluoro lights to cheesy pop groups wearing badges that said ‘I like Swipe”.

We had long hair. We were anti-establishment. We were in the rock industry. We got arrested.

Literally everyone smoked dope, pot, ganja, weed, cannabis, bongs, joints and spliffs. Sometimes all at once. LSD and acid were prevalent. Heroin wasn’t on the scene, neither was cocaine. Alcohol was part of the mix, but most gigs were in halls that weren’t licensed.

There were some discothèque venues that programmed bands, and towards the end of the decade the pubs started to open up in a big way as audiences grew up, coming out of the schools and community halls.

The police were very interested in long-haired hippy rock-types, and would routinely pull us over and search us. There were no breathalysers so we were more prone to drink-driving. Sydney to Melbourne required a bottle of Southern Comfort.

We had just escaped the national draft, which Whitlam abolished a few years earlier. Soldiers returned from Vietnam were pilloried as murderers and didn’t go to rock gigs.

Sex was happening everywhere. The worst thing that could happen was you got venereal disease and had to visit the Blue Light Clinic to deal with the riot in your underwear—thanks to Billy Thorpe for that quote.

The pill had liberated women and the media was full of free love and desire. Number 96 was a TV soap that featured women taking off their clothes in every episode. If you couldn’t get laid, it was because you were too afraid to ask. Guys virtually did just that: see a girl at a gig, sidle up and suggest a walk outside. Code: have sex.

Girls didn’t think of themselves as groupies. They would simply try and do anything to get close to their idols. Crews were well placed as intermediaries. Pants down, transaction, introduction, and a motel room number. After load out, of course.

On the road we would pull into a town, circumnavigate the main street, and back up to the rear of the hall. There was always a hall attendant to open up, and usually the place smelled of fresh floor polish. The timber floor was all pristine, and there was usually a plaque above the stage commemorating the fallen.

By the end of the night we would be in some fluoro-lit fibro motel room with a ceiling fan and a breakfast hatch on the wall, keeping the rest of the place awake with booze and girls, yelling and smoking.

Sometimes an enraged father would arrive with a couple of uncles, looking for Darlene, Debbie or Donna. Sometimes we would get run out of town by the police.

Some of the bigger bands played extremely hot gigs packed with thousands of punters. There were no controls on venues, no noise laws, and no reason to cool down a hot crowd who would drink more.

Press reports had some rock stars needing oxygen side-stage. We carried a tank alright, but it wasn’t oxygen, it was nitrous oxide. You could buy it anywhere they sold industrial gas, no questions asked.

We bought CO2 gas for our Genie foggers and pneumatic lighting stands. So adding on a cylinder of nitrous was easy. If they asked, we said it was for the caterer, since they used it to whip cream.

Sucking a face full of that stuff gave you a rush, but it also knocked you out. I had a balloon full one night after a gig and woke up after hitting the floor. I was being tenderly ministered by a girl—her care extended beyond a bandaid. Some girls respond well to blood, it seems.

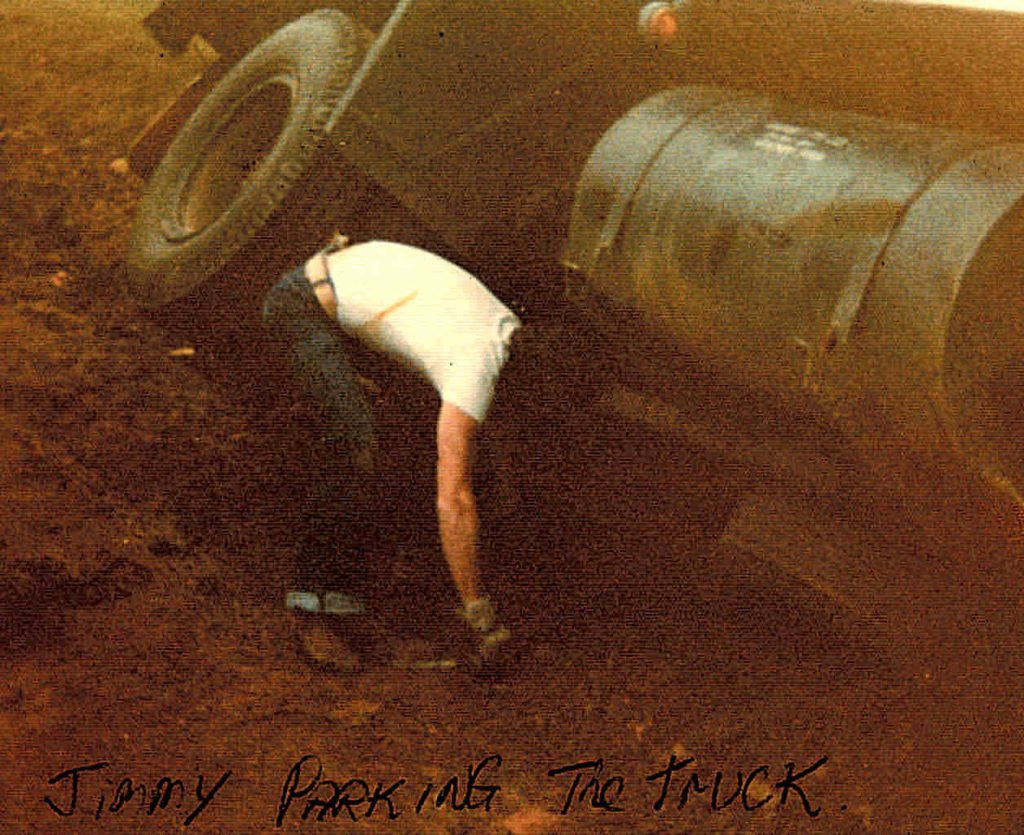

We were primitive. But the conditions were too. Air conditioning wasn’t common. Deodorant was Uncle Sam, or Brut 33. The truck was petrol-engined with four on the floor. Power brakes were a luxury, power steering very optional. The truck cabin had a vinyl bench seat, no heater, no radio, and no air vents.

Phones were made of Bakelite and phone numbers had six digits. To call interstate or overseas you needed an operator. Air tickets were crazy expensive, and exactly the same price on TAA or Ansett.

Even the flights left at the same time – Australia had a two-airlines system that was totally regulated. Two competing DC9s would take off from somewhere ridiculous, like Proserpine, and land at the same time in Brisbane.

There were no faxes; we used telex machines that fed out typed telegram-style messages, or we sent a telegram, and presumably some kid on a bike would deliver them. The last telegram I ever got was from a girl. “I hate your guts,” it read.

We wore denim, and tee-shirts, and running shoes. Our long hair was greasy and the food was too. McDonalds had just opened at Yagoona in Sydney, and Kentucky Fried, as it was known back then, had been going a while. Fast food was more commonly made by a Greek guy in a blue coat at a suburban takeaway and washed down with a milkshake.

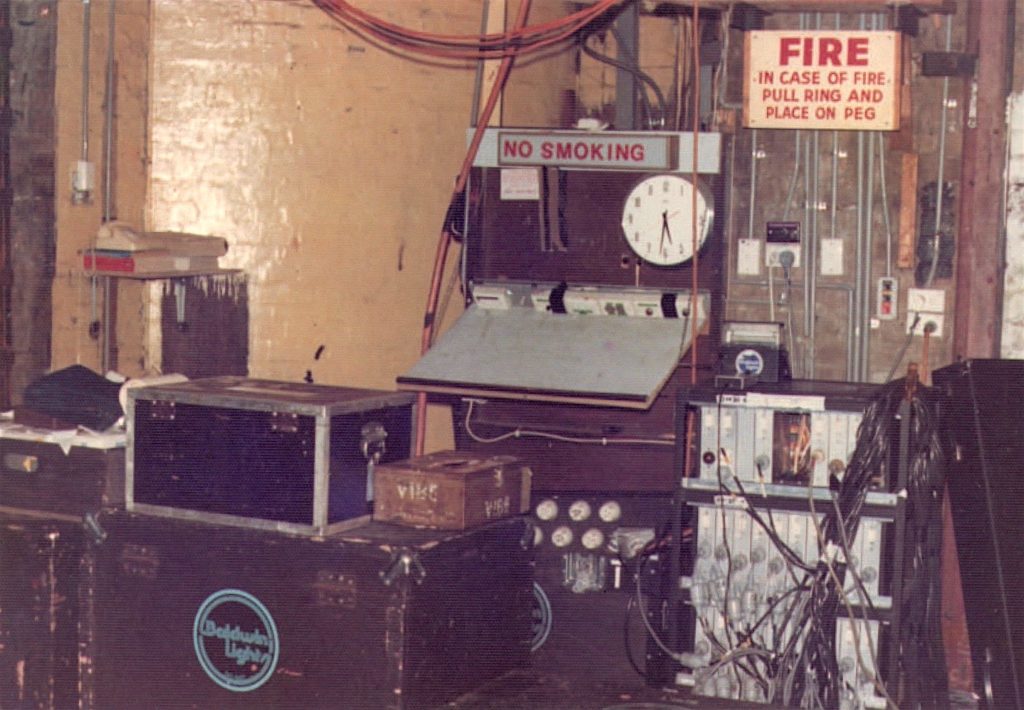

At the gig there was no three-phase power, which is the safe way to run lots of electrical equipment. We scrounged single circuits from around the place, running long leads. Soon we needed more. (Related reading from CX Network – ‘Skills We Had, Skills You Have‘)

The Miniset 10 dimmer and the new Jands dimmer needed three-phase, so we made our own single-phase to three-phase adaptors. But to get real power, you needed to tap into the switchboard at the gig.

We did it live, with the master switch on, screwing bare wires into the back of the porcelain fuse holders.

There was no FM radio, only AM with the radio station names printed on the tuner dial. 2SM, 3XY … those radio stations had immense power, and the DJs would routinely turn up at gigs in their tight denim flares and walk out with a gorgeous woman. We wore platform shoes, men had perms. We all had too much hair, everywhere.

Bands would be paid maybe eighty bucks as a support act through to a couple of hundred bucks for a headline show. Crew got about ten dollars a night each. The Sydney Harbor Bridge toll was twenty cents.

Legends were born, but some were killed off early. Safety was not a concept. There were a series of road accidents, the most horrible involved two Swanee crew members whose truck ran off the Hume Highway and burned down to the wheel hubs.

Because we were ready and willing to drive overnight after a gig, usually fuelled by drugs and booze, we were more prone to dying. It helped if the band paid for the drugs and booze – somehow that seemed an honourable arrangement. Death seemed less fatal then than it does now.

It was ridiculously easy to smash the car, truck, or van. My Kombi came to an early end on the Bulli Pass when I ran into a truck. I remember the random thought at the moment of impact; “Gee, the truck is inside the Kombi, on the passenger seat. I could reach over and touch the side.”

I walked away, not scratched, covered in glittering windscreen shards and soaked from the rain.

One night my Ford F350 truck ran off the road and, as it careened out of control, brushed an overhanging tree branch. I had been asleep behind the wheel, and the branch gave me enough of a wakeup to somehow bring the thing under control and not hit anything.

I found out how a rental car will spin out of control. I did it once on the Pacific Highway, and once on the New England Highway. Somehow there was a break in the oncoming traffic both times. I also found out that those speed advisory signs on corners actually make sense. I overshot a corner – and again there was fortunately a break in the oncoming traffic.

Fall off a tall ladder and not break any bones? Get hit over the head with a steel bar and just bleed without brain damage? Maybe I was brain damaged.

Then heroin did become a thing and there was a rash of deaths associated with the drug as people miscalculated doses. For all who died, there were just as many lives wrecked or simply left behind.

A lot of brains were fried by drugs, plenty became alcoholics, and some people were taken out back and bashed senseless by uncles or fathers or bouncers or gangs.

A bashing was seen as something routine and I don’t remember anyone afraid of being charged with assault. You were judged by how you handled yourself, how you handled your liquor or alcohol, and how many women you laid.

Those of us who established families left our beloved at home to become rock and roll widows, expected to be happy with the occasional phone call. Some crew burned the relationship candle at both ends; free love meant no responsibility. Women with women. Wives with mates. Mates with wives. Men with men. Nothing was going too far.

Insidiously there were underage girls everywhere, and no one seemed to go to jail for carnal knowledge when birthdays were revealed. There was a totally alien and almost surreal attitude to morality which we’ve dramatically reprogrammed since.

There was no responsibility for anything. Like when some genius at Hertz decided to “corner the music industry” and they hired us Falcon wagons and trucks at flat rate with no insurance excess and a no-fault replacement scheme.

We put two new wagons into wrecker yards on one trip to Queensland, yelling at the Hertz chick when we were forced to await a replacement for two hours in Kempsey.

For a while we blew things up, until it got ugly and someone got killed.

I experimented with gunpowder. If you mixed in some magnesium powder it got brighter. But then I discovered a fireworks company would sell flash powder over the counter, so I was typically carrying a kilo of grey powder in my attaché case.

We had flash pots and strips of roof gutter filled with a trail of powder. If we didn’t have igniters, a camera flash bulb would do it. We had twelve-volt power supplies and a firing board, and too much fun. Sometimes the band got more than they bargained for. We didn’t care.

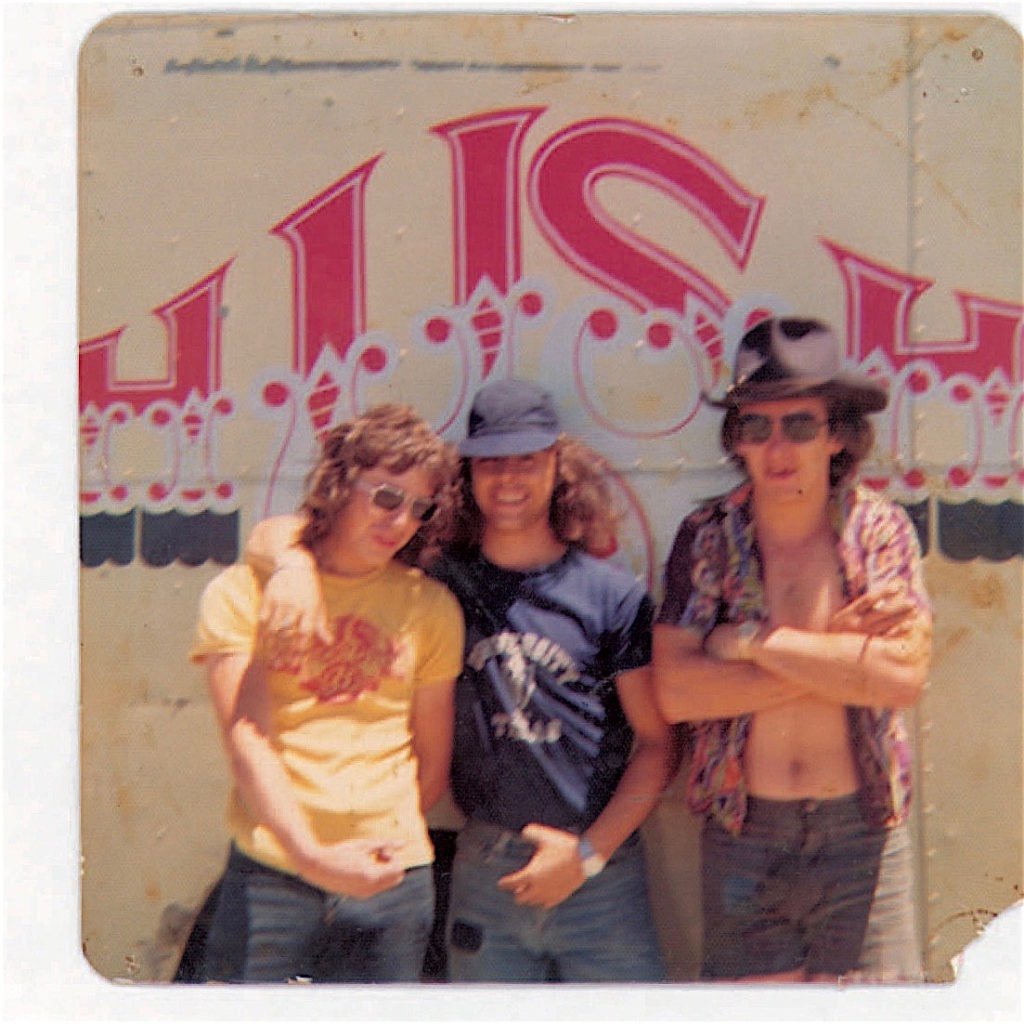

The music industry grew at a staggering rate through to the first half of the 1980s. Bands could and did sell hundreds of thousands of vinyl albums and singles, promoters and managers could and did skim plenty of money off the gullible. If you’re drunk and stoned, it’s hard to count banknotes. (Related reading on CX Network – ‘Hush On Tour: Exploit The Crew‘)

The audiences were bedazzled by the emerging colour TV, and Countdown came along. But cinema sound was basic and movies couldn’t compete with the loud ballsy sound we produced.

We had big bottom end and sizzling highs, and our lighting rigs were bright. We were technicolor in a monochrome world.

There seemed to be no stopping the music business. By the end of the decade, halls were giving way to beer barns and pubs that crammed in 1,500 punters. When The Angels and Cold Chisel toured, the door gross could be over $10,000 in cash.

The highways always had a band truck passing by. We used to spot the other crews, meet them at roadhouses, and stop when they broke down. By the early eighties we were all driving five-tonne Isuzu pantechs, and soon eight-tonners. Still with no air conditioning, still with vinyl seats.

I remember the summer heat in Queensland, windows open, sweat dripping out of my shorts onto my thongs. Bare-chested. Swigging Fosters down the highway. A cassette tape of Little River Band playing.

My girlfriend chucked a banana milkshake out the window and it blew right back in. The back of the truck – hot as hell. Inside the gig, stale beer smell, sweat, puke, de-odour gas on sticky pub carpets. Gaff tape on everything, sharp staples from hastily hung stage rags.

Innocently yelling “hang the blacks” (the backdrop) and getting into a fight with a table full of aboriginals in a beer garden.

Big and packed venues like the Playroom on the Gold Coast, Bombay Rock, and the Bondi Lifesaver, small and packed venues like the Manzil Room or the Khardoma Café. Strange pubs in country towns, little bowling clubs whose secretary managers had been stitched up by a booking agency into believing that paying $8,000 for a band on a Tuesday would save the place.

There was a lot of cash changing hands. I was always pushing a drug dealer out of the way to get paid by the tour manager. Some people fabricated some wild stories about why and how money had disappeared. Lies and more lies, promises and unreality. Just show me the money.

It was still the cash era, before electronic banking, before computers or internets, no emails, no GST, no mandatory reporting if you deposited twenty grand cash at the bank. Mainly the cash was kept out of the bank and dished up in one and two dollar bills stuffed into the attaché case that was de rigueur back then.

The rip-offs were routine, the cheque often bounced, and hollow promises were thick on the ground. There were bikers, fires, fists and guns. Hookers and dealers, groupies and managers, record company staff who really thought they wrote the songs, and booking agents who lied for a living. Dope, diesel, and degradation.

Then there were the rock stars. Amongst the struggles, drugs, fatigue, violence and the egos, there were some people who were complete utter bastards, who practiced the art of duplicity and who just didn’t care about others.

A few still work in the industry and are well-avoided by those who remember—most of the rest are dead. I smelled the turning point in 1984 and got off the road, a road that peaked with Whispering Jack shifting twenty-four platinum records several years later. Somehow we faded as our audience grew up and had kids.

AIDS and random breath-testing took the fun out. Bolivian marching powder—cocaine—and speed made people crazy. How would you feel? You’re tired, jaded, trying to do your gig, and a guy is yelling spittle into your face for no reason, or trying to take a swing at you? Telling you that you can’t do this or that, turn the PA down, just being ridiculous. Refusing to load out after the gig—the list goes on. I remember them all. Sometimes the best response was a microphone stand over the head. Take a nap, sunshine.

I carry enough scars, enough broken teeth, and like most old roadies I have a back injury that flares up when it is cold. And I’m half deaf, with a liver that’s suffered more than most.

We fought, we struggled against the authorities, we exceeded our limits, and we had a burning passion for the music. Ours was a generation with a big gap between us and the confused pre-war generation who parented us.

These weren’t the good old days at all, really; these were bad times with flashes of brilliance. I used to cringe when someone called me a roadie. Now I’m proud of it.

You should have seen that damned Clipper coach …

This Could Be Serious by Julius Grafton.

Get your copy at:

juliusgrafton.com $14.99

Apple bookstore $11.99

Apple audio book $21.99

Amazon Kindle $11.99

Amazon paperback $30.99

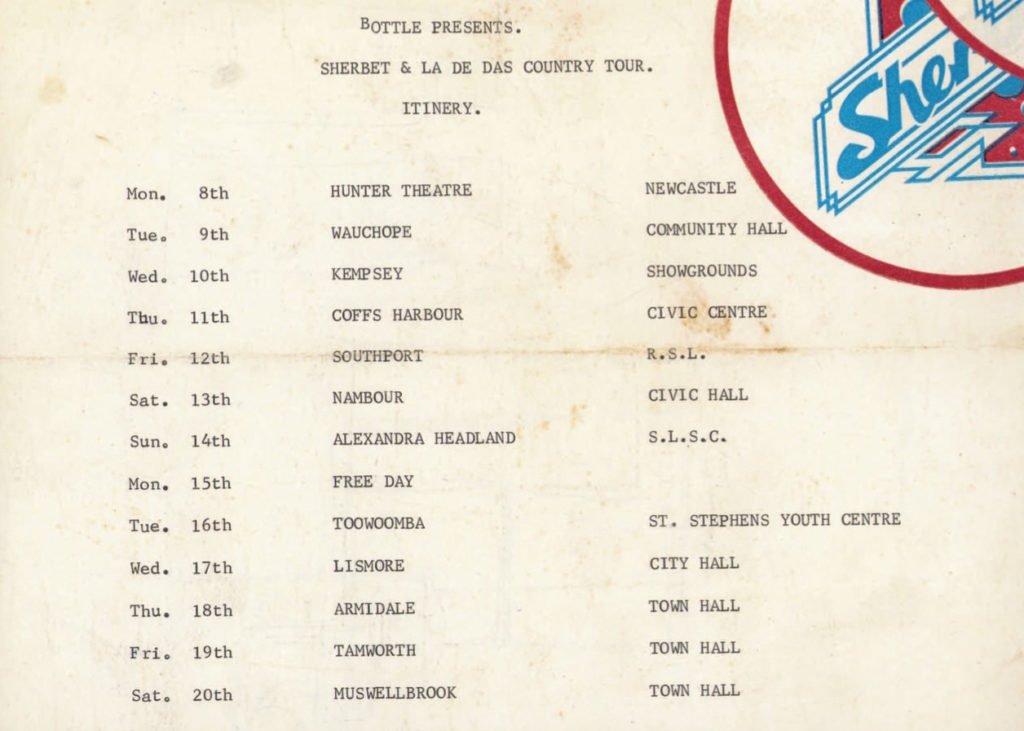

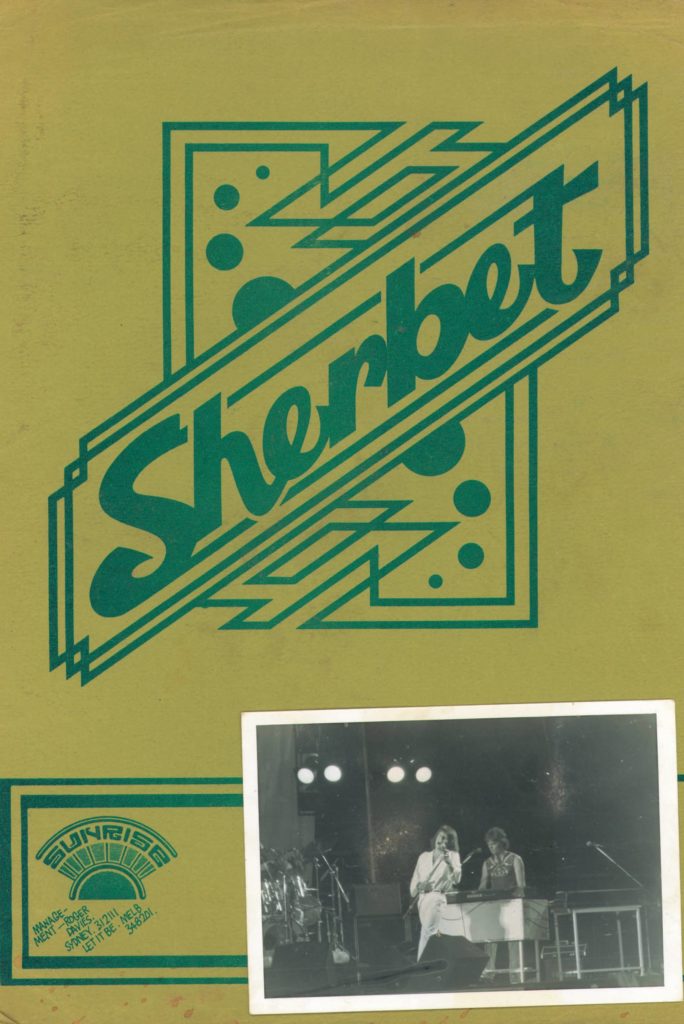

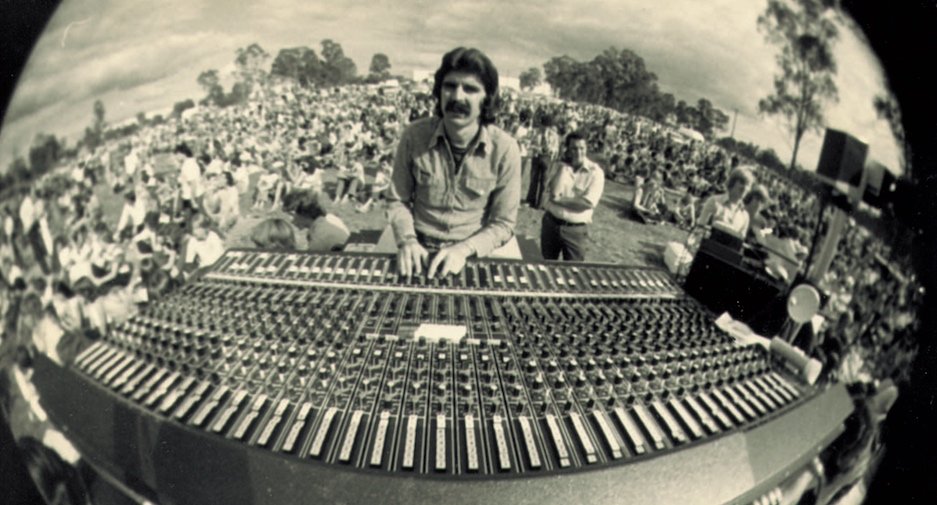

All Images: History of Roadcrew exhibit, various photographers, compiled by C. Baldwin, G. Harrison and J. Grafton, 1999.

See also:

‘Hush On Tour: Exploit The Crew‘ by Julius Grafton, CX Magazine March 2015 https://www.cxnetwork.com.au/hush-on-tour-exploit-the-crew

‘Skills We Had, Skills You Have’ by Julius Grafton, CX Magazine April 2019 https://www.cxnetwork.com.au/skills-we-had-skills-you-have

‘Bygone Times’ by Julius Grafton, CX Network 2002 https://www.cxnetwork.com.au/bygone-times

‘History – 47 Years of Jands Lighting Control 1971-2018‘ by Julius Grafton, CX Magazine Dec-Jan 2019 https://www.cxnetwork.com.au/history-47-years-of-jands-lighting-control-1971-2018

EXTERNAL LINKS:

’30 Year History of Rock Lighting and Sound in Australia’ by Grahame Harrison, Colin Baldwin & Julius Grafton, via Colin Baldwin Consulting website – HTML or PDF [Links valid Dec 2020]

Website: The History of Live Production in Australia, featuring stories, pictures, videos, memorabilia via Colin Baldwin Consulting – http://history.colinbaldwin.com [Link valid Dec 2020]

CX Magazine – December 2020

LIGHTING | AUDIO | VIDEO | STAGING | INTEGRATION

Entertainment technology news and issues for Australia and New Zealand

– in print and free online www.cxnetwork.com.au

© VCS Creative Publishing

Subscribe

Published monthly since 1991, our famous AV industry magazine is free for download or pay for print. Subscribers also receive CX News, our free weekly email with the latest industry news and jobs.